Classics tend to be the films that have (or will) stand the test of time – films that shaped culture or defined it, films that solidified cinematic language, films that told stories for generations to come. At this point, there’s a general cinematic canon that people consider to be all-time “classics” – whether that’s determined through lists like Schneider’s “1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die,” IMDb’s ever-changing top 250, the word of great critics like Ebert, or even popular opinion on internet forums and social media. But because of this saturation of opinions telling us what is and is not an undeniable masterwork, the word “classic” has become increasingly devoid of meaning or weight.

And because certain films pop up in this discourse of what is “classic” more frequently than others, films that are arguably just as great as the big names lose the spotlight they deserve. With that in mind, here’s a list of ten underappreciated classics that are worth checking out (and if you have already seen them, more power to you!).

1. Vampyr (1932, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Vampyr is a horror-fantasy film directed by Danish filmmaker Carl Theodor Dreyer, most notable for directing The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Originally, the film was received with generally negative reception, but where Vampyr lacks in plot ingenuity, it makes up for in gorgeous black and white cinematography and gloomy atmosphere.

The film follows an occult-obsessed traveller named Allan Gray, who arrives in the town of Courtempierre on a dark, dreary night. While sleeping in an inn, Gray is abruptly awoken by a mysterious old man, who leaves him a packet with an inscription ordering Gray to open upon the old man’s death. Gray leaves the inn in search of answers; what ensues is a classic vampire hunting tale.

With its roots in German Expressionism, Vampyr has an irresistibly gothic, fable-like atmosphere – a film of creeping shadows and hazy moonlit fields. The simplistic pulpiness of its premise allows leeway for the film’s eerie aesthetics to shine bright; Vampyr is one of the most underappreciated horror classics of the 1930s and a true visual masterpiece of the era.

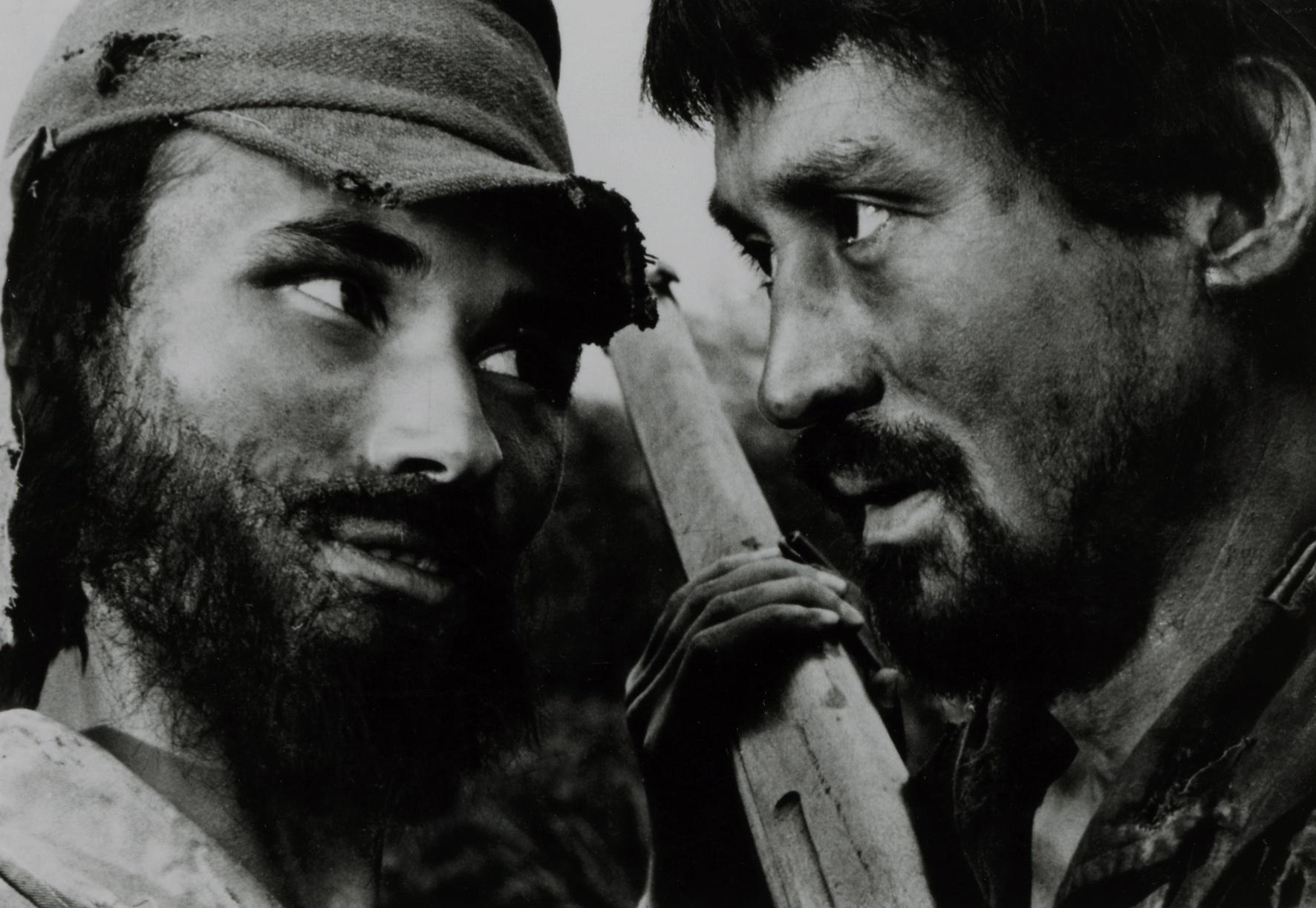

2. Fires on the Plain (1959, Kon Ichikawa)

Alongside the greats of classic Japanese cinema like Ozu and Kurosawa, Kon Ichikawa is a gifted and lyrical director whose filmography has unfortunately been overshadowed by his contemporaries. Ichikawa’s unsung masterwork, Fires on the Plain, is one of the most sobering and bleak war films to come from the era.

Taking place on the eve of WWII, the film follows a Japanese soldier, Tamura, stranded in the Philippines and cut off from aid or support by the Allied Forces. Tamura and his fellow soldiers, completely disoriented and demoralized, face sickness, starvation, and insanity on the island. The film follows Tamura’s grueling tale of survival.

Especially for the time it was released, Fires on the Plain is an incredibly cruel and violent film. Ichikawa is unafraid to display the bloody horrors of war and the demoralizing taboos faced by soldiers caught in the midst of it: most notoriously in this film, cannibalism. Fires on the Plain is a film that believes in the human spirit and its determination to survive against all odds, but Ichikawa identifies the elephant in the room: at what cost? How much humanity can one lose to survive? It’s a harrowing and absolutely unforgettable war film, completely ahead of its time and a true classic of Eastern cinema.

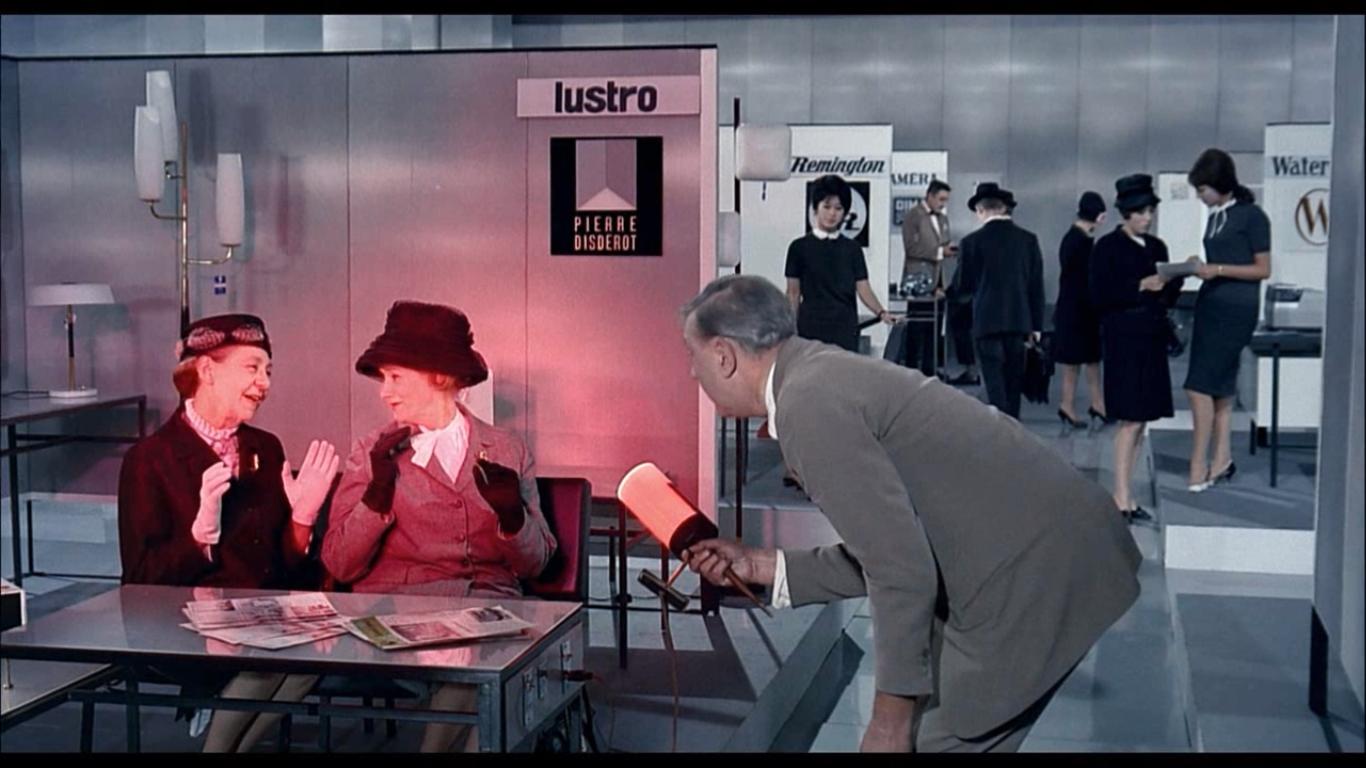

3. Playtime (1967, Jacques Tati)

Playtime is a comedy film directed by the great French filmmaker Jacques Tati. Not unlike Charlie Chaplin and his “Tramp” character, Tati directs and stars in his films as a recurring character called Monsieur Hulot. And not unlike Chapman, Tati is a master of using comedy of errors as a means of identifying a greater discrepancy or truth in contemporary society.

The film takes place in a near-future Paris over the course of a day. Across the film’s runtime, Monsieur Hulot stumbles and bumbles around this modern, high-tech megalopolis, attempting to make sense of the city. Meanwhile, an American tourist visiting Paris crosses paths with Hulot. Hijinks ensue.

Shot in 70mm, Tati’s vision of the near future has a distinctly mid-century modern tinge of retrofuturism that is unbelievably gorgeous to look at – the sets are elaborate and the world-building is fully realized. But the film’s mechanical, tech-driven environment and the slapstick visual comedy that results is really no laughing matter.

Tati’s vision of the future is one where people are unable to communicate; where technology and industry (quite literally) blocks humans from building meaningful connections and understanding one another. In this way, Playtime is more relevant in the digital age than ever before, a film that is playfully wary of our increasingly detached and distracted Western culture. It is equal parts a classic of visually-driven comedy as it is a classic of socially-aware science fiction.

4. Wake in Fright (1971, Ted Kotcheff)

Wake in Fright is an Australian psychological thriller directed by Ted Kotcheff, who would later go on to direct popular American classics like First Blood (1982) and Weekend at Bernie’s (1989). Although it was welcomed to positive critical reception upon release, the film’s objectionable content (notably a harrowing scene involving hunting live kangaroos) resulted in its financial failure. And because the film’s master negative went missing, for the remainder of the 20th century Wake in Fright became unavailable to view in its original unedited form.

It wasn’t until the film was resurrected and restored in 2009 that audiences were able to experience the film as it was originally intended to. The film follows an Australian school teacher, John, forced to teach in the outback of Australia on financial bond. As the holidays approach, John plans to catch a plane and visit his girlfriend in Sydney, but is stranded in a small town called The Yabba en route. What initially appears to be a minor setback becomes psychological and physical hell as John is unable to leave the rudimentary, drunkard town.

If there was ever a film that made you want to grab a beer… Wake in Fright is not it. It is one of the quintessential films whose horror is founded in intoxication; total disorientation and a loss of self. Few films have captured an individual’s downward spiral into moral degradation, violence, helplessness and hedonism with such stomach-churning brilliance. Wake in Fright is an earth shattering thriller in the best ways possible, and a true forgotten classic of the Australian New Wave.

5. Tale of Tales (1979, Yuri Norstein)

Tale of Tales is a short Soviet animated film by Yuri Norstein. When it was released, Tale of Tales was deemed by several sources to be the greatest animated film ever created. Of course, many animated films have been released since 1979 that could just as easily contend for the title, but Tale of Tales is still undoubtedly a masterpiece not just of animation, but of filmmaking in any genre.

Not unlike the works of other great Russian filmmakers like Tarkovsky, Norstein uses his film as a means of exploring memory through vignettes and iconography – the memories of a nation, of childhood, and a loss of innocence. In this way, the film does not have a chronological plot in a traditional sense. The film floats back and forth between abstracted, even nostalgic images of wartime, nature, and family in Russia, almost all with a curious little grey wolf at its center. Norstein combines stop motion with paper puppetry and photography to a truly luminous, haunting effect.

The entire film has a deep sense of loss and longing – remembering, in small blurs, gentle lullabies of the past, empty homes and streetlights, the dying embers of a fire. The eyes of the little wolf were allegedly created using cutouts of an old photo of a half-drowned kitten; the wolf guides us on this path of lost innocence, himself a relic of something innocent and precious on the verge of being lost. Norstein’s masterpiece is a lyrical, spectral and completely unforgettable classic of Soviet animated filmmaking.