Let’s start by quickly defining what a dystopian film constitutes. The term dystopia is the antonym of utopia. Whereas utopia refers to an imagined place or state where everything is perfect, dystopia refers to a state or place where everything has gone to hell. Per their very definition, films dealing with dystopian themes are therefore at the very least speculative and almost always to some extend part of the science fiction genre. The films often deal with totalitarian societies or ones that have degraded environmentally or socially.

Dystopian movies seem to be one of the current fads in film, or at least when it comes to the teenage market. The Hunger Games proved to be a great financial success and in its wake films like Divergent and more recently The Maze Runner have managed to do great business as well. None of those movies will be found on this list though. In fact, instead of being great examples of dystopian films, they might be proof that we are indeed living in a dystopian society ourselves.

On this list, you’ll find twenty of the greatest dystopian films to have ever hit the screen. As per usual, it isn’t a be-all and end-all summary of the best dystopian films ever and the list could easily have been expanded to thirty titles but I decided to stick to twenty in an attempt to keep the selected entries of the highest calibre.

Some of the films which did not end up making the cut but were considered are Escape From New York, Robocop, Strange Days, Alphaville, Silent Running and Code 46. Anyone with a serious passion for the genre should make sure to also watch these titles as well as plenty of others. That being said, the twenty titles listed here are all fantastic examples of the best the genre has got to offer.

20. Nineteen Eighty-Four (Michael Radford, 1984)

Let’s start with perhaps the most famous title associated with dystopian totalitarian fiction, 1984. Based on the infamous novel of the same name by George Orwell, which gave birth to the term “Big Brother”, this second adaptation for the screen, which release year clearly coincided with the year of its title (the first adaptation was produced in 1956), is directed by Michael Radford and stars John Hurt and Richard Burton, in his final screen appearance.

The film is set in London in 1984, which is the capital of the territory of Airstrip One (formerly Britain), which in itself is part of the larger totalitarian state of Oceania. Winston Smith (Hurt) is a bureaucrat working for the Ministry of Truth, where his job is to constantly rewrite history according to the Party and its omnipresent leader Big Brother. Whilst free thought is forbidden and everybody is under constant surveillance, Winston keeps a diary of his private thoughts.

Worse still is the fact that he meets Julia (Suzanna Hamilton), another worker within the Ministry of Truth, and that the two start a relationship, something which is also strictly forbidden by the Party. The relationship lasts for a few months but comes to a sudden end when they are caught by the Thought Police and Winston is taken into the Ministry of Love for interrogation and rehabilitation by his former friend O’Brien (Burton) who takes him to the feared Room 101, where people are tortured by being confronted by their worst secret fears.

Staying pretty much faithful to its source material, 1984 is a very bleak and grim affair. The future is made to look especially drab, washed-out and grey, perfectly conveying the lack of humanity as well as the omnipresence of the Party. So much so, that this adaptation actually suffers a bit from its all-encompassing grim mood, making it not the easiest film to sit through.

John Hurt is fantastic as Winston Smith, whose face perfectly conveys his long mental tortured existence and Burton also does an admirable job as the face of the Party, putting in a truly frightening performance. Hurt won a Best Actor award at the Fantasporto Film Festival whilst both actors walked away with the same prize at the Valladolid Festival.

19. Battle Royale (Kinji Fukasaku, 2000)

Adapted from the novel of the same name by Koushun Takami, Battle Royale is a Japanese futuristic action comedy with a healthy dose of black humour, set in a society gone mad.

As the economy has worsened and more people have lost their jobs, Japan is on the verge of chaos, especially as the country’s youth has responded by becoming more rebellious and delinquent. The government has therefore taken drastic measures and created the Millennial Reform School Act, a nationally televised game in which random high school classes are selected in their entirety and sent to a remote island to hunt each other down until only one remains standing.

The film focuses on the class of Kitano (Beat Takeshi), a twisted school teacher whose class has been selected, and Shuya Nanahara, one of the students in his class, whose father has committed suicide.

If you’re not into violent films, you might want to skip this one. Basically the Japanese exploitation version The Hunger Games (although Battle Royale came out a decade earlier), the kids here are fitted with explosive collars which decapitate them if they leave the designated playing area and an on-screen counter which keeps track of how many of the students are still alive.

But if this sounds like it might be your cup of tea, then chances are you are going to love this one with the added bonus that the film is also remarkably funny. A dark, disturbing and unique film, Battle Royale is part exploitation, part satire and 100% twisted.

18. City of Lost Children (Jean-Pierre Jeunet & Marc Caro, 1995)

The second feature directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro, after their debut breakthrough Delicatessen, The City of Lost Children is a dark science fiction/fantasy film starring Ron Perlman.

Krank (Daniel Emilfork) is a mad scientist who lives on an ocean rig and cannot dream. He has however devised a machine that can steal the dreams of others and in order to so, he kidnaps children from a nearby port town. But when he takes a little boy named Denree (Joseph Lucien), he hasn’t counted on his older brother, the giant One (Perlman) to come looking for him.

When One arrives at the the rig he teams up with a little orphaned girl named Miette (Judith Vittet), who is part of a guild of thieves which is completely made up of orphans. As they make their way towards Krank’s lair, they encounter a pair of Siamese twins, a talking brain in a fish bowl and a bunch of clones, all played by Jeunet regular, Dominique Pinon.

With their second feature, Jeunet and Caro created a visually distinct and inventive dystopian fantasy world with elements of steampunk (before the term was widely used and popular), freak-shows and dark fairy tales. The films production design, costumes, cinematography and boundless imagination are indeed its strongest points whilst their storytelling was critiqued by many a film critic at the time of the film’s release. The fact that Ron Perlman, who did not speak French, learned all his lines phonetically, probably didn’t add to his performance either.

The film did however almost immediately gain a cult following, which has only grown over the years due to its truly unique look and feel. The City of Lost Children was nominated for a Palme d’Or at Cannes and also received four nominations at the César Awards in France for Best Music, Cinematography, Costume Design and Production Design, only winning the last one.

17. Soylent Green (Richard Fleischer, 1973)

Loosely based upon the novel Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison, Soylent Green is a 1973 science fiction film set in a dystopian future directed by Richard Fleischer.

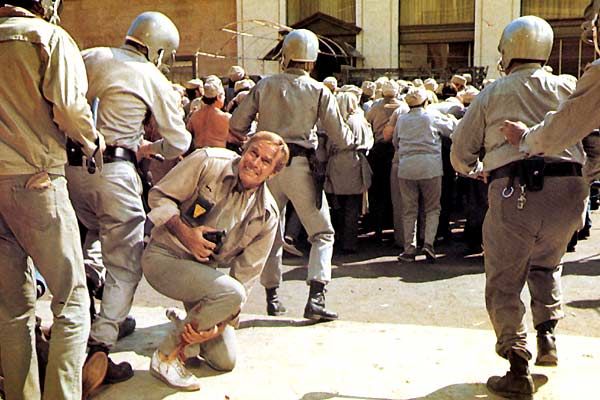

The year is 2022 and the world is suffering from overpopulation and horrible ecological conditions due to the greenhouse effect. Food is in very short supply and most nutrition is supplied by the Soylent Corporation who have just introduced their latest food source: “Soylent Green”. In this landscape, detective Frank Thorn (Charlton Heston) is assigned to investigate the murder of a wealthy industrialist who turns out to have been on the board of the Soylent Corporation.

Together with his friend and house mate “Sol” Roth (Edward G. Robinson), he starts unravelling the case but the Governor orders the case closed when too much of an underlying conspiracy is being unearthed. Nonetheless Thorn keeps investigating and his friend Roth makes a shocking discovery about the true nature of Soylent Green.

Whilst the visuals of Soylent Green have not withstood the test of time very well, the story itself still packs a punch and is a prime example of the many 1970’s science fiction films to contain strong social commentary.

The film also marked the last role for screen legend Edward G. Robinson, who died 12 days after shooting was completed, and his euthanasia scene in the movie is even more moving as a result. Whilst Soylent Green is a bit of an uneven film, it is an absolute must-see for science fiction lovers, especially if you like your science fiction laced with powerful social themes.

16. The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

Based on the novel of the same name by Franz Kafka, The Trial was adapted for the screen and directed by Orson Welles, in what is arguably the best cinematic adaptation of one of the author’s works.

Joseph K (Anthony Perkins) is woken one morning by some men, who refuse to identify themselves, and put under open arrest for a crime which goes unmentioned for the entire duration of the film. From there on in Josef K tries to seek explanations and justice in a seemingly endless and completely illogical bureaucracy.

During his travels and search for answers, he converses with his neighbour (Jeanne Moreau), a lawyer (Orson Welles), the lawyer’s mistress (Romy Schneider) and the wife of a courtroom guard (Elsa Martinelli) but all is to no avail as this whole world seems to be set up to drive one to the edge of insanity. Ultimately, Josef K is sentenced to death, without him ever knowing what it is he has actually been accused of.

Labyrinthian, maddeningly frustrating, psychologically brutal and truly Kafkaesque, The Trial’s strong points can also easily be seen as its weak points. A frustrating film to sit through, which can leave one wondering what the hell one just witnessed, this sort of seems to be the point as the viewer experiences the same frustration and despair as Josef K does.

Stunningly shot in black and white, the film’s sets and cinematography do a great job conveying its themes and Anthony Perkins is perfect as the man who doesn’t get anywhere no matter how hard he tries. Whilst the film was largely dismissed by critics at the time of its release, it did win the Critics Award for Best Film by the French Syndicate of Cinema Critics and was nominated for the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. The film later gained tremendously in status for some although others will still tell you its a style over substance head-scratcher. And whilst that may be correct, I think that’s sort of the point.

15. Twelve Monkeys (Terry Gilliam, 1995)

Inspired by one of the greatest short films ever made, La Jetée by Chris Marker (which did not make this list as it was recently included in my Post-Apocalyptic one), 12 Monkeys is directed by Terry Gilliam and stars Bruce Willis, Madeleine Stowe and Brad Pitt. The film is part of Gilliam’s dystopian trilogy, preceded by Brazil (also mentioned on this list) and recently concluded with The Zero Theorem.

The central premise of 12 Monkeys is time travel. In a future society a plague has wiped out most of the earth’s population and those who are still alive are forced to live in underground caves as the air outside is poisonous. In this world, James Cole (Willis) is a convicted criminal, who gets the chance to be pardoned if he agrees to undertake a dangerous mission by travelling back in time to obtain a sample of the virus and find out more about a terrorist organisation called The Army of the 12 Monkeys, which was involved with the outbreak of the virus.

He is first mistakenly sent back to 1990, where he ends up in a psychiatric ward and meets Dr. Railly (Stowe) and the crazy son of a virologist named Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt). After being brought back to 2035, he is sent off again, first arriving in WWI, before finally reaching 1996, the year he was always intended to end up and where he will have find out if Goines and his organisation are behind the outbreak of the virus.

Giving Terry Gilliam the greatest commercial success of his career, 12 Monkeys is an intricately scripted time-travel flick, taking place in various times and dealing with dreams, madness and a world which has gone to pieces. Gilliam manages to get some excellent performances from his cast, with Willis putting in one of his career’s highlights and Pitt arguably proving for the first time that he was far more than just a pretty face (along with Seven, which was released the same year).

Whilst falling short when compared to its brilliant source material, 12 Monkeys is a zany and fun sci-fi flick that seems to be bursting at the seams but ultimately still manages to keep things together. The film received two Academy Award nominations, including one for Brad Pitt as Best Supporting Actor. And whilst he did not win it, he managed to take home the same prize in the same category at the Golden Globes that year.