6. Kagemusha (1980, Akira Kurosawa)

Kurosawa is a director whose work and impact requires no formal introduction. One of his most highly regarded works is Ran (1985), a sweeping Shakespearean samurai epic in full, vibrant color. But Ran could not exist without Kagemusha, which Kurosawa often refers to as a dress rehearsal for Ran’s production. Diminishing though this description may be, Kagemusha is in more ways than one on equal footing with Ran as a masterpiece of Japanese feudal fiction.

The film follows a thief who, by chance encounter, is hired to stand as a double for an aging warlord because of their similar appearance. But once the warlord dies, the thief must take the roll as the ruler he previously impersonated.

Kagemusha is one of Kurosawa’s greatest tragedy epic; it is a film of incredible power, emotion and scale. It is, further, one of his most visually stunning works. Kurosawa uses color in a way that transcends realism, creating a spectral space of baroque light and shadow, passionate sunsets and hand-painted dreamscapes. Kagemusha is a singular and unforgettable cinematic experience, never to be diminished in the shadow of its big brother Ran.

7. Big Night (1996, Stanley Tucci and Cambell Scott)

Big Night is a dramedy directed by Stanley Tucci and Cambell Scott. The film follows two idealized but ideologically clashing Italian immigrant brothers, Primo and Secondo, who run a failing Italian restaurant. In desperation, the two brothers plan a massive banquet under the prospect that Louis Prima is coming to their restaurant, in hopes of revitalizing the reputation of their business.

As far as films about food go, Big Night is one of the most appetizing, witty and thoroughly enjoyable. It is at times hysterical, at times bittersweet, and a total joy to watch through and through. Without exaggeration, the final scene of the film is perhaps one of the most understated and perfect gestures in cinematic history. It is a film about family, about love, and most importantly, about food, and the way it brings us together.

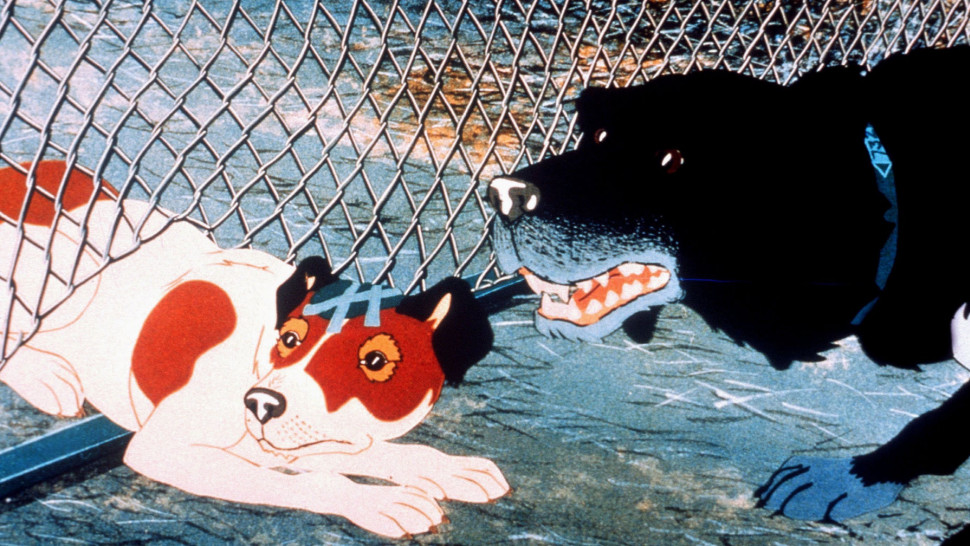

8. The Plague Dogs (1982, Martin Rosen)

The Plague Dogs is an animated film by Martin Rosen, who also directed the 1978 adaptation of Watership Down. Despite the unassuming appearance of the film’s art style, The Plague Dogs is by no means a children’s film, but a somber and adult take on Richard Adams’ novel of the same name.The film follows two dogs who escape from a British research lab. The dogs must fend for themselves while fleeing from their captors in the wild.

Perhaps the most affecting aspect of Rosen’s film is the subversion of expectations inherent in its presentation. The Plague Dogs plays like a typical Western animated project, but the themes and undertones of cruelty and occasional bursts of shocking violence undermine the otherwise harmless premise of dogs surviving in the wilderness. In this way The Plague Dogs is an unparalleled and deeply underappreciated classic of adult animation, one of subtle devastation and helplessness rather than the gratuitous excess frequently prevalent in the genre.

9. Nobody Knows (2004, Hirokazu Kore-eda)

Hirokazu Kore-eda is one of Japan’s most prolific and internationally praised contemporary directors, especially in light of his 2018 critical darling Shoplifters. Often compared to Yasujiro Ozu, Kore-eda’s films are consistently minimal, humane, and empathetic. Unfortunately, the earlier works of his filmography are often overshadowed by his more recent endeavors like Shoplifters. This is true of Nobody Knows (2004), perhaps Kore-eda’s most heart-wrenching early work.

The film is based on the true story of a twelve-year-old boy named Akira, played by Yūya Yagira, and his three siblings. Neglected and left alone by their mother, the children are left to fend for themselves in a small Tokyo apartment, awaiting the uncertain return of their mother.

Kore-eda has always shown a profound understanding of youth and innocence, but never to the extent shown in Nobody Knows (2004), a film devoid of any adults for the majority of its runtime. Starring all non-professional actors, the film has an incredible realism and ernesty in its performances that only furthers the emotional gravitas of the children’s situation. Yūya Yagira, deservingly, became the youngest person to ever receive the Best Actor award at Cannes film festival.

Nobody Knows is a film of incredible beauty and empathy, and also a film of overwhelming injustice and tragedy – a film that honors the resilience of the human spirit as much as it highlights its complete fragility under the weights of the world. It is one of Kore-eda’s greatest films and an absolute classic of humanitarian cinema.

10. Old Joy (2006, Kelly Reichhardt)

Directed by Kelly Reichhardt, Old Joy is a criminally overlooked micro-indie road film, whimsical in its simplicity and honesty. Boasting a wonderfully dreamy soundtrack from the rock group Yo La Tengo, Old Joy explores what it means to be content through casual conversation (or the lack thereof) in a way that is at times comedically awkward, at times painful and somber, but usually both at once.

The premise of the film is simple. Mark gets a call from his old buddy Kurt. The two reunite to take a weekend camping trip to a hot spring in the Cascade mountain range. The majority of the film’s brief runtime is comprised of Mark, Kurt, and Mark’s dog making the trek out to the hot spring. The two attempt to reconnect in spite of their now completely different walks of life – Mark, who has now settled down with a wife and a kid, and Kurt, who continues to live an untethered hippie lifestyle.

People change, friends come and go, and life moves on, sometimes without the people that used to be a big part of it. Old Joy perfectly captures that feeling – trying to rekindle memories and companionship with someone from your past just for a moment, even if things will never quite be the same. Reichhardt uses the often mechanical and aimless conversations of Mark and Kurt as a platform to express isolation and dissatisfaction in an ever-moving, ever-convenient, ever-comfortable modern world.

Mark and Kurt, in their own different ways, just want to believe they’ve done or are doing something meaningful. At the end of the day, people just want to be told it’s going to be ok; that someone out there still cares about them. Old Joy doesn’t claim to have answers, but it brilliantly captures a simple, even anticlimactic moment of intimacy between two lost friends trying to make sense of their place in the world. It’s bittersweet in the best ways possible, and a true overlooked American indie classic.