Great and admired films come along every year. Fewer stand the test of time, and even fewer ascend to the status of classics. The films listed here can be considered a few points shy of each level on account of controversy, critical drubbing, audience rejection, reevaluation in light of current trends and events, and of course, zeitgeist defining praise or mockery.

They all have something in common though, and that is their connection to pop culture machine and what it has to say about us the viewers. Be forewarned, spoilers abound, not just for plot points, but for the way you look at these films after reading.

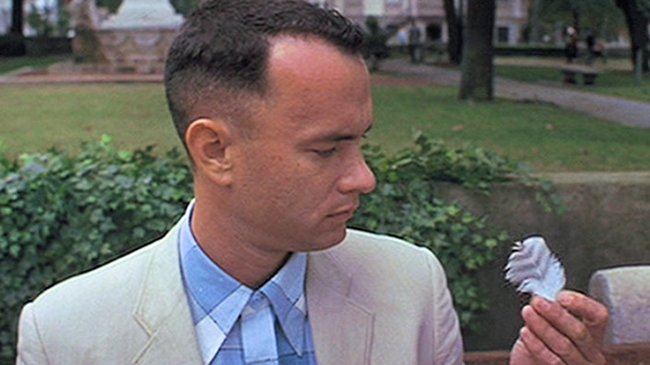

1. Forrest Gump

Not the baby boomer fantasy most people take it for, but more a critique of America’s dumb luck.

1994 was quite a watershed year for social upheaval in the United States. As The People vs. OJ Simpson: American Crime Story gave us much needed context in 2016, the beginning challenges to white male baby boomers was still fresh.

From President Clinton’s loss of the democratic majority in congress, to alternative nation simultaneously reclaiming hippy culture via Woodstock, while also challenging social norms even beyond hippie ideals, the lost America of the 50’s and 60’s was reevaluated and found lacking. Enter Robert Zemeckis’s Forrest Gump.

The story follows a simpleton on a journey through most of the pop cultural highlights of 1950-1980. Sometimes he is at the periphery, other times directly involved with events ranging from meet-cutes with presidents, to calling in the Watergate scandal by accident. He even becomes a millionaire thanks to down-home country work on a shrimp boat.

All of this amid the turmoil and elation of the post WWII era. Forrest (ironically named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, of KKK fame) even helps out a number of African Americans on his way to a quiet life in the south. A dumb white man, according to the film, did more for black people than they could do for themselves.

Upon release, the movie was critically praised and commercially successful. At awards time the film was honored as the living Norman Rockwell painting it purported to be. Backlash was inevitable and over the years the film has weathered reappraisal for its politics and trivialization of social events.

What gets missed in the two camps that have sprung up around the film is the more nuanced interpretation that Forrest represents more of American dumb luck, than any calculated method at success via hard work or pluck. By trivializing history, this film gives viewers a front row seat to a history largely played out in Time or Newsweek of the era. It is intentionally cartoonish for those that would take it seriously, and character driven at times for those who do not.

A great example of this interpretation, in a film that has many, are the many intimate relationships Forrest has. Much like all Americans, history happens around our daily lives, and Forrest is no different. The three meaningful relationships he has in the film all involve people outside the historical events he stumbles into.

The heart of the film are these relationships, the historical trappings are there to stoke nostalgia. But that nostalgia is manipulated in order for people to see the truth about America. Regardless of our standing in the world (as of 1994 that is) we are just as dumb and lucky as the rest of the planet in making our way through history.

Some folks see Forrest as an ideal of simplicity and hard work, and others see him as a white male taking credit for everything from civil rights to the Smiley Face t-shirt. And just like Lt. Dan’s new space-age legs, there is an illusion and a reality to help make that point. Forrest is us.

2. Die Hard

How this entire movie is a microcosm for our political/social landscape today, which gestated in the 80’s when it was made.

Foreign terrorists invade a Japanese company with headquarters in Los Angeles during a Christmas party. They want to steal millions in bearer bonds, which are untraceable. A plucky New York cop foils their plans.

At the time it was made Die Hard got one thing wrong for audiences decades later in 2017. The country of the people that owned the building. Throughout the recent presidential election several times China, not Japan, was mentioned as looming large in the American economy for any number of different reasons, the largest being it holding so much of American debt.

Bearer bonds are such debt and were a staple of 80’s era Wall Street deals. Greed was indeed good. Add to that vague European “terrorists” that were really pitiless thugs looking for a payday and you have another situation rife for reevaluation today.

And smack dab in the middle of everything is a white male cop just struggling to save his estranged wife, shame on her for having a career, from not only the raiders inside, but the inept bureaucracy outside attempting to negotiate with something other than a 9mm Beretta. The FBI, the city police, and the news all converge to perpetrate/witness a bungling operation that is only resolved by the working man with real talk and improvised fire-power.

Sadly, this used to just be a movie in the 80’s. But that decade, which gave rise to the likes of Donald Trump, inspired no doubt by Reagan’s policies, panache, and Hollywood pedigree, gave us the short hand for movies of its ilk, and a short hand for the American ability to utterly destroy the building where the hostages are kept with righteous machismo. They even had the guts to create a bro-mance between a white NYC cop and a black LA policeman.

3. Memento

Leonard doesn’t have amnesia at all, he willfully lives in denial of events he can’t accept, and creates scenarios where he is the hero.

Near the end of the film Leonard (Guy Pearce) sits in his truck, a few moments before what we already know is Teddy’s (Joe Pantoliano) death, and contemplates who his next John G. should be. John G. is the man he has been chasing the entire film to enact revenge for his wife’s murder. But the audience just found out a few minutes before that Leonard and his wife survived the attack that gave Leonard anterograde-amnesia.

A lot of viewers have assumed that the twist of this film was that Leonard was Sammy Jenkis, but a closer reading reveals an even more startling twist: Leonard doesn’t have amnesia at all, at least not in the sense the film has played with up until that moment.

Since the film runs backwards we see the same shots over again throughout the film, but always slightly different, kind of like a memory that changes over time. Small tweaks change the shots, or the context in the film until we come to the end, which is actually the beginning. This entire method of narrative trickery is in service not to a clinical case of amnesia. Failure to make new memories, albeit a strong motive for a thriller already, is a dodge for a more common sort of mental incapacity: denial.

Yes, perhaps Leonard’s wife died in the attack he couldn’t stop, or she died due to his neglect/head injury, but she is somewhat a symbol throughout the film of who he used to be with her, regardless of how she died. He is consumed with an all-encompassing guilt, which pits him into a never ending cycle of denial and a self-sabotaged search for a man that may not exist.

The key is in that penultimate scene where Leonard watches Teddy go into the building and decides that he will be his next John G. “Now…where was I?”

4. JFK

A critique of “historically” accurate entertainments about historical events – as American as apple pie.

Oliver Stone and his films are no stranger to controversy. Much like Zemeckis’s entry above, he was (used to be at least) obsessed with baby boomer pop-cultural touchstones of the 60’ and 70’s.

From Platoon to Nixon he ran the decades through his meat grinder and came up with some delicious sausages made of fact, conjecture, rumor, and fabrication. His films have been criticized for their political stances, but what is intriguing about what many consider his masterpiece, JFK, is how much that film relies on an American audiences’ acceptance that world spanning conspiracies exist.

From quacks talking about chem-trails to 9/11 being an inside job, conspiracy theories are as American as apple pie. The mother of all conspiracies is the JFK assassination. This film satisfies that urge to blame cabals of the unseen intelligence state for problems at home, or relish grand mysteries that lie at the heart of a historical event that many think changed America forever. This film also throws every theory into the kitchen sink and blends it up in the disposer.

Does Oliver Stone really believe all these theories? And does he not realize that if as large a group as Jim Garrison believed was responsible for the assassination existed, wouldn’t one of them have written a NYT bestseller by now?

Perhaps Oliver Stone wasn’t out to prove who actually killed JFK, perhaps his entire film is a mirror for average Americans to look through to see that conspiracy theories have become a part of our cultural heritage, somewhat confirmed with Nixon a decade after the events of the film.

The major takeaway from the film is that if you throw enough plausible, even if untruthful, information at anything, people will give up and tow a party line because they can’t make sense of all the conflicting information. The assassination of JFK started all this.

It has become common place to discuss and watch feature films that involve an underdog surmounting an evil totalitarian state. What is truly scary today, is that the supposed underdogs are who installed the despot we now have.

5. Prometheus

Humans and the Xenomorphs are equally Frankenstein-like monsters created by The Engineers, and therefore share responsibility for the events of the film franchise.

So many filmgoers were upset with Ridley Scott’s return to the Alien franchise. Even before the film was released it garnered attention for the coy way in which the filmmakers refused to reveal that it was in fact an Alien prequel. Not sure it has even been settled today, and characteristically, the non-sequel sequel to this non-prequel prequel hits theaters in May with the same hype. Only this time we will actually see a Xenomorph, or so the previews show us one.

What got lost in the shuffle of all the Alien universe hype, and which still to this day takes a back seat when talking about the original film, is man’s connection to the alien (via gestation, which would suggest a common biology) and the alien’s connection to human creations such as Ash and David (androids that figure quite prominently in the plots of both the original and the prequel that is not a prequel).

What we find in Prometheus (think Frankenstein’s subtitle as well as Greek myths) is that the Engineers developed a way to seed worlds with what could be considered a blessing (when it creates humans) and a curse (when it creates the “perfect organism” of death). What a glorious way to answer the lingering questions of the Space Jockey than with: They created us and the Xenomorphs out of the same material, which turned on them, and therefore they must destroy all their creations.

The connection to our own creations turning on us is answered fully with the nefarious, if programmed, natures of Ash and David. Just like the monster in Mary Shelley’s book, it only wants to be loved by its “father” and rejects him when he is not.

A lesser complaint about Prometheus involved the subpar “scientists” that come along on the mission. Well, in a future that has a robot like David to take care of so many things while humans sleep the journey away, how smart do you think the guys that volunteered for the secret mission actually were?