Kids are cute. Agreed. And one of the great appeals of watching films about children is the pleasure we get from that cuteness. But children also have a special ability to inspire other moods and sentiments which would fall flat if evoked through adult characters; and Iranian filmmakers in particular have used this infectious quality of childhood to create some truly exceptional films.

It’s not exactly a secret, but placing the vulnerability or the naïve exuberance of children at the centre of a film can have profound effects. A violent world is always most alarming, and our empathy for others is more than a little bit heightened, when a child’s involved. And just as much, a story told through the eyes of a child can help us believe a little more fully, can capture our idealist tendencies more completely, and draw us willingly into less cynical ways of seeing the world.

It’s not just Iranian cinema which has drawn upon this potential, of course. However, the tendency in Iran to focus its storytelling on low-key, everyday events has opened up that potential to highly unique perspectives.

All of the films below, in their own way, have use the idealistic and empathetic identifications which adults have with children to subtly evoke specific ways of seeing the world. Rather than just raising the emotional stakes to make us feel dramatic twists more deeply, child characters have fostered intimate perceptual insights into the experience of living amongst people.

And peppered throughout, there’s some highly original cinematic experiences which underline Iran’s growing reputation in the film industry.

1. Bashu, the Little Stranger (Bahram Beizai, 1990)

In 1999, Bashu, the Little Stranger was voted the best Iranian movie of all time by a poll of 150 movie experts. It’s not hard to see why, either. It’s a wonderful expression of human interaction, which is at once a realist film about prejudice and a fairy-tale-like piece of storytelling which kindles a profound experience of what it means to belong.

In fact, there’s a sort of earthy purity running through Bahram Beizai’s movie which brings to life basic experiences like love, acceptance, unfamiliarity, and isolation at their rawest moments of instinctive contact, creating an enchanting cinematic journey which is just as unique as it is touching.

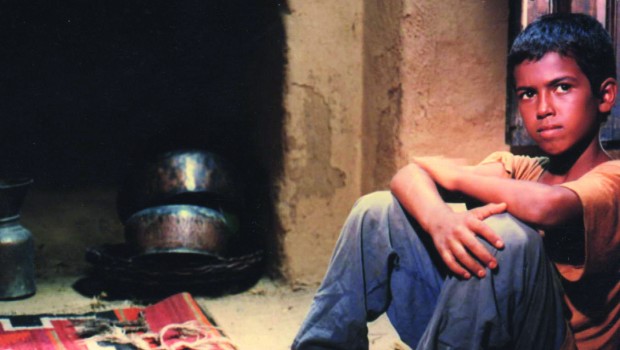

Broadly speaking, the film tells the story of Bashu as he’s torn from his home in the south of Iran, and is gradual accepted within a village further north.

Coming to the area alone and by chance after traumatically seeing his parents killed during an overflow of fighting in the Iran-Iraq war, Bashu is a little stranger traumatised by violence and loss. He’s been stripped of everything he knows and loves, and must make a new home in a village where his native people are ridiculed.

This premise of a traumatised child in a foreign place works so well because the empathy it evokes channels into a visceral, almost tactile, sense of Bashu’s experiences. Indeed, when first he’s noticed by the other main characters of the film – Na’i and her two young children – there’s a sort of primal physicality to the encounter.

As he loiters cagily at the edge of their farm, Nai’ first shoes him away then coaxes him with food, and the actions of the scene combine with the light, earthy tone of the film to shine naturalistic purity on Bashu’s character. It’s a general affect, moreover, that continues throughout the film, particularly within the lush expression of rural charm provided by Na’i, which border on a supernatural relation to wildlife.

At any rate, initially rarefied through this first naturistic encounter, Bashu slowly becomes an intimate member of Na’i’s family. And although he’s initially shunned by the wider community, just as Na’i is hounded for taking him in, he eventually wins their love too. But it’s the way this all happens that makes the film special.

Relearning every human need and emotion as if it’s taking place for the first time, Bashu, the Little Stranger reveals the nature of belonging in a way that our usual familiarity with people all too easily hides.

2. Mourning (Morteza Farshbaf, 2011)

Mourning belongs to a class of modern Iranian cinema which has perfected the art of unspoken statements, and Morteza Farshbaf’s directing debut is a masterful example of how a poetry of visual images, sound and silence can heighten storytelling with a subtlety which defies words.

Indeed, so much poignantly expressed meaning and psychological complexity emanates from this technique that the emotional journey of the child in this story – Arisha – is conveyed perfectly, almost without him saying anything.

Basically, it’s a road trip movie in which a deaf couple, Kamran and Sharareh, drive their nephew Airsha across the hilly landscapes of Iran. They’re heading towards the dead bodies of Arisha’s parents, who died in a car crash after leaving Arisha with his aunt and uncle during the course of an argument. But the tone of the film is much lighter than that plot suggests.

And the mourning process of the title takes place with great nuance, expressing its movement through the development of visual tropes and taking place in the background of Kamran and Sharareh’s interactions.

Effectively, what unfolds is a tender portrait of the way communication defines the liveability of a person’s life. As it becomes clear that Airsha’s parent’s incessant arguing has made his life unbearable, his complex ambivalence to their death is played out as his aunt and uncle begin to argue about their potential to be his guardians.

The communication barrier of Kamran and Sharareh’s deafness is thus beautifully contrasted with the much more profound inability to hear born of discord, suggesting a glimmer of a life for Arisha in an essentially loving home.

Yet it’s just a glimmer, shrouded with more ambivalence. And as Arisha silently responds to his aunt and uncle’s argument, it’s ultimately the fragility of a liveable life and a mourning child which comes into the foreground, stirring in the final moments with an elegant and thought-provoking open-endedness.

3. Children of Heaven (Majid Majidi, 1998)

Majid Majidi’s classic family film was nominated for the best foreign language Oscar on its release, and for good reason. It’s not easy to make a film that’s completely free of cynicism without it becoming unconvincingly idealistic. But Children of Heaven is so thoroughly charming that you can’t help but be drawn into the warm and hopeful world it creates.

The world in question is a gentle one, populated by poor but affable characters that get by simply by helping each other. It’s a softened world where the villains are simply crotchety school teachers, and where small accidents are the real adversaries. And it’s a world with a beautifully elevated sense of everyday hopes and dramas, where a pair of pink shoes becomes the locus of love, dismay, suspicion, and gallantry.

That pair of pink shoes belong to Zahra, and the story begins when her older brother Ali accidentally lets them get thrown away by a bin collector. Worried to tell their parents about such a significant loss for a poor family, they conspire to share Ali’s shoes. Zahra will wear them in the morning, when she goes to school, and give them to Ali in the afternoon when his classes begin. There’s not quite enough time, however, and although Ali races across the city every day to meet his sister, he’s continually late.

The way Children of Heaven draws the audience into this small drama is spellbinding. In beguiling scene after beguiling scene, the importance of Zahra and Ali’s shoes are given a new twist. And you couldn’t really root for these two kids more, as more small accidents befall them and they help each other through it all. Ultimately, however, it’s the run to school which proves the vital plot line.

Discovering that there’s a children’s foot race where third prize is a pair of sneakers, Ali knows he’s fast enough to win them for Zahra, and enters. There’s one more accident left to come, though: Ali gets so caught up in the race that he comes first rather than third. Yet despite his disappointment, it doesn’t seem to matter too much in the end. As Ali soaks his tired feet in a pool there’s a lingering sense that they’ll get by nonetheless, simply by helping each other.

4. The White Balloon (Jafar Panahi, 1995)

More than any other film on this list, The White Balloon is purely an expression of childhood. Simply put, it expresses what it’s like to be a child with an absorbing vividness, taking us on a journey through the kind of utter fixations children have with things that fascinate them, the sulky intensity of their disappointment, the confusion and vulnerably of coming upon an adult world they can’t control, and the ability to turn on a dime from a bad mood to a good one.

All this is moved along by a simple plot in which seven-year-old Razieh wants to buy a fish, but isn’t allowed. After some unrelenting pleading and some adorably sad frowns, however, she’s finally given a 500 Toman note and runs off determinedly to get it. But she loses the money twice along the way, sending her into a chain of encounters which director Jafar Panahi unfolds in typically captivating style.

The first time Razieh loses the money provides a profound taste of childhood vulnerability. Distracted by the curiosity of a crowd blocking her view of something, she weaves her way between the legs of the audience and finds herself at the centre of a snake charmer’s performance.

The sense of her being overwhelmed by the scene is striking from the start, but when the snake charmer gets hold of her money – which is held innocently in an open jar – and uses it in the act Zahra’s stifled desperation becomes palpable. It’s a sublime moment evokes an intimate sense of her mood.

Finally, Razieh gets the money back, puts the episode behind her in an instant and races off towards her fish – only to drop the money down a grate at the entrance to a shop.

It’s really out of reach this time, and the rest of the film concerns its retrieval. More adorable face pulling ensues here, as Razieh goes to stare at the fish with longing and discusses her woes with various strangers. But eventually her brother Ali enlists the help of another child, a balloon seller, who eventually sets the world to rights.

Brandishing a stick with a single white balloon tied it, they manage to reach down and pull the money out via chewing gum suck to the end. Everything’s forgotten again, and Zahra trots off contentedly.

5. Abidanis (Kianoush Ayari, 1994)

Writer and director Kianoush Ayari’s heart-felt piece of social commentary was inspired by the 1948 Italian movie, Bicycle Thieves. Like Vittorio De Sica’s masterpiece, it tells the story of a father searching a war torn city with his son, desperate find a stolen vehicle which he needs for their livelihood.

Only here it’s a car rather than a bicycle, the city is Tehran rather than Rome, and it’s the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war rather than World War II.

Seen through the eyes of a young boy, the film follows Borna and his father, Darvish, across Tehran as they search scrap yards in the hope of recovering their car. It’s a simple but powerful story which unearths something of the social devastation which Iran suffered in the wake of the war, and Borna’s presence in the search holds a youthful mirror to that gritty reality.

Borna, in fact, carries a broken shard of mirror with him throughout the film, playing with it curiously to look about from different angles. And it’s his looking about gives a sense of intimacy to the visual world of Abadanis – a world of contorted metal, concrete walls and rubble, atmospherically shot in black and white to bring a grimy, textural background to the character interaction.

But more than that Borna’s naïve helpfulness and bravado brings a sense of patient expectation to the panorama of desperation, petty crime and wheeler-dealing revealed in Abadanis.

For there’s still a sense community still alive beneath the disarray. And it’s a spirit of determination in the face of adversity that defines Darvish and Borna’s search – covered in dents and chugging along, like the car they finally find, but still moving forward.