Science Fiction cinema is usually an invitation to enter a new world or dimension. Metropolis was a statement on how modern day society needed to function in a dismal future setting. Blade Runner was a reinvention of the noir genre that incorporated a prediction of what may become of us. E.T. The Extra Terrestrial was a proposition, that perhaps we needn’t be afraid of what may be out there. Lastly, of course, any Star Wars film is an excuse to use the terrains and space of an entire galaxy as a thrill ride.

The beauty of the science fiction genre is that it can be used to distance an audience whilst pulling them in. Not all questions are answered right in front of you. Some films of this nature require mental work to appreciate, but they leave a lasting impression on you as a result.

A very common example would be the two works by Christopher Nolan: Inception and Interstellar. On the surface, Inception is a heist film and Interstellar is a journey. Toss in the layers of dream states or the shifts in time through the laws of the fifth dimension, and you have a more difficult story on your hands.

This list is not finding the hardest science fiction films to digest, but some challenging films lie ahead. This list, rather, is a celebration of these kinds of films because of their ability to truly pull us in to these new worlds. Nothing is spoon fed to us. We search for many of our own answers. Most of the time, we have different results than our peers, and that is half of the joy.

Here’s a toast to the sci-fi cinema that opens our perceptions whilst scrambling the inner contents of our brains. Here are the ten best mind bending science fiction films of all time.

Keep in mind, there are spoilers ahead for every film involved.

10. Moon

Decades before Duncan Jones tried his hand at filmmaking, his father David Jones, known better as the late David Bowie, wrote about the adventures of travelling into space and never returning (as well as the visitors from space that recorded their findings on Earth).

As if it was destined to be, Jones’ first film is easily his greatest triumph. The deceptively low budgeted Moon, starring Sam Rockwell countless times over, brings forth the idea that a lone worker in a unit on the moon has almost finished his three year shift. He daydreams and imagines what he sees, shortly before he suffers an accident, and wakes up as if nothing had happened.

Suddenly, one iteration of Sam notices another, and the notion of clones is introduced. We begin to wonder how deep the rabbit hole goes, and so do the clones that are alive. What started off as an honest mission begins to turn into a statement on the expendability of the employed (with a twist, of course). How much of this is in Sam’s head, and how much is real?

The film turns into a game of chess, where information has to be moved from pawn to pawn before they are wiped out. For such a small production with limited capabilities, Moon goes the extra mile through its clever meandering of withheld information.

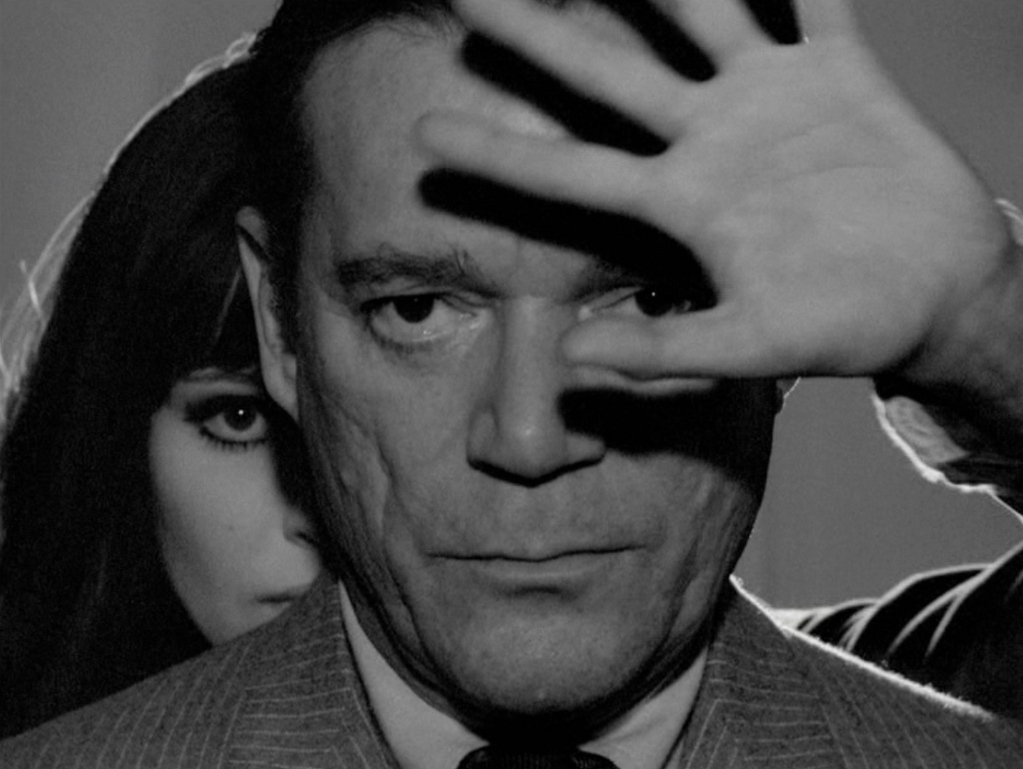

9. Alphaville

This is one of the strangest science fiction films ever created, because none of it actually features created sets or props to instill a fictitious universe. This is all France, but the right parts of France were picked. Jean-Luc Godard—the master of shattering a film and piecing it back together—uses fragmented shots and images slapped together through edgy editing to create a new universe through a new cinematic language.

Lemmy, played by Eddie Constatine, is an agent that has business to attend in the titular Alphaville. A super computer system, named Alpha 60, works like a Big-Brother of Orwellian proportions; the entire place is surveyed to the point of zero privacy.

Like 1984, no one is allowed to think freely; unlike many 1984 adaptations, it’s as if Alphaville has restricted its audience in the same way. In one sense, the jarring pairing of images and sounds, of which seem like harsh mixtures, forces you to think of a unity through whatever you find.

While this does give you the right to think, it also forces you to work with what you are given, without much breathing room to pick your own gazes and sounds. The film slowly transitions into a more conventional piece when Natacha (Anna Karina) begins to let go of her own restrictions; the music swells and joy can finally be found.

8. Arrival

Arrival is a straight forward film for most of its duration. Denis Villeneuve sacrificed his usually-dismal signature style for a presence of hope; most of this lies upon the shoulders of Amy Adams’ Louise character. Louise is part of a project that is working on discovering why alien beings have landed in various locations on Earth. She, as a linguistics specialist, is called on board to decipher the language of these terrestrials.

Sounds simple enough, right? Things start to get a bit difficult when the “heptapod” words (of which are purely visual and not audibly based) translate differently with the English words that Louise and the other chosen linguists of the world have provided.

The film finally takes a completely different turn for the final act. Time travel, in a very different way that most cinephiles are accustom to, is thrown into the mix, and we are suddenly led into a fragmented labyrinth. If this was not enough, the previous events of the film are now affected by this new series of events, as their origins are questionable.

The beauty of having this element sprung upon you is that you experience time travel directly. You cannot pick apart how some things changed or did not change, because you are only seeing the current iterations of each scenario. The film resolves with a gorgeous ending, where the pairing of intelligences from different species resolves in the saving of both kinds (of past, present, and future).

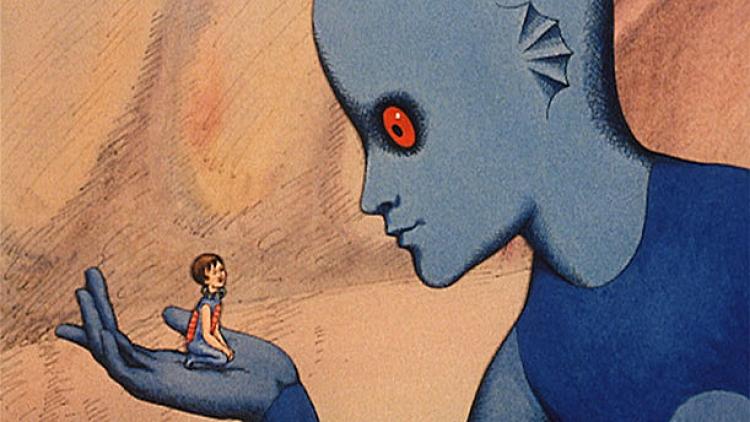

7. Fantastic Planet

The only animated film featured on this list, Fantastic Planet has a cult following for being one of the biggest mind fucks in cinema history. While the story that René Laloux directed (and co-wrote with Roland Topor) is pretty basic, it’s the world that he showcases that throws you in for a loop. Humans are treated like domesticated pets by Draags (gigantic blue creatures), and we witness an uprising for humans to be freed from their predicament.

Fair enough, that is easy to follow. Yet, in almost each and every scene, there is one piece that does not make sense in the grand scheme of things. This can apply to how nature behaves, how past times on the planet Ygam function, or why the hell a cloud is laughing and making noises.

Because the film is animated (and almost looks like scientific drawings come to life), it can get away with anything. Without limitations, each and every scene is flourished with unusual traits that sometimes only apply to that specific scene. It opens the idea that we, perhaps, are not even close to knowing about every little detail of Ygam, as we only are seeing what the captured humans are seeing.

At the same time, with the doses of nightmare fuel we get in just seventy minutes alone, do we want to know what else Ygam has to offer? Part of these images is to ensure us that we want to get the hell out of there, like the humans (or Oms, as they’re called) fighting for freedom.

6. Annihilation

The most recent film on this list is still fresh in the minds of many. Part of this is due to the production failures that have let the ambitious film and its creator (Alex Garland) down. The film gets tossed into Netflix’s distribution, but also sprinkled into a few North American theatres for a few weeks only. It’s as if most of the executives on board had little faith in this film.

It’s a shame, because Annihilation is some of the most modernist filmmaking you can find in a high budgeted mainstream picture. A group of female experts in a variety of fields (including biology and anthropology, amongst others) venture into a rainbow-coloured nightmare known as “the Shimmer” to try and find out why the previous explorers never came back (or came back in critical condition).

Once you enter the Shimmer, the film is never the same. The stock-sound guitar soundtrack slowly shifts into different territory; it ultimately turns into an experimental electronic trance. The cohesion between flash backs and current events slips away; there is not a specific reason for the images you see.

The film instills more fear of what you do see rather than an unknown. By the time Natalie Portman’s character (Lena) is literally fending her own double, the film has become a completely different beast. This heavily-changed world is almost impossible to explain. By the ending credits, full of fractals and visual splendor, you, too, are permanently affected by the Shimmer (well, unless Lena never came back, and we are only seeing her double return).