“Each film brings out the moralist in the director and makes each of them a filmmaker of cruelty,” stated Truffaut in his introduction to Bazin’s “The Cinema of Cruelty.” Iconic auteurs, starting with Bunuel and his “Andalusian Dog,” have stressed the importance of cruelty in the shaping of society and released films that deployed their artistic efficacy in showing ways of suffering and making suffering happen.

Being cruel is not synonymous to being violent: violence has hurting or causing death as a consequence. Cruelty plays more with intentions and the absence of feelings, such as compassion and sympathy. It is mostly a sentimental lacking that can be expressed even by violent acts.

However, in this list, it is not the consequences but the intentions that count. That is why one won’t find films such as “Murder by Numbers” or “Benny’s Video” where emphasis is given to the act of killing. Not even “La Haine” or “If,” where the use of violence has obvious social motives.

Childhood, adolescent and youth cruelty has always been dealt by literature and cinema as an anomaly. The first years of somebody’s life are supposed to be the most tender ones, the age of innocence. So cruel underaged people are faced either as monsters or young creatures which hard living conditions led them to cruelty. When we talk about groups of people, explanations are tried to be found in the social contouring.

The protagonists of these movies are either cruel youths or victims of other young people’s cruelty. Their motives vary, and the explanations about the cruelty vary as well, according to each director’s perspective. Some focus on individuals, others treat violence as a social phenomenon, some go far beyond than that.

So here we go with Cinema of – Youth – Cruelty.

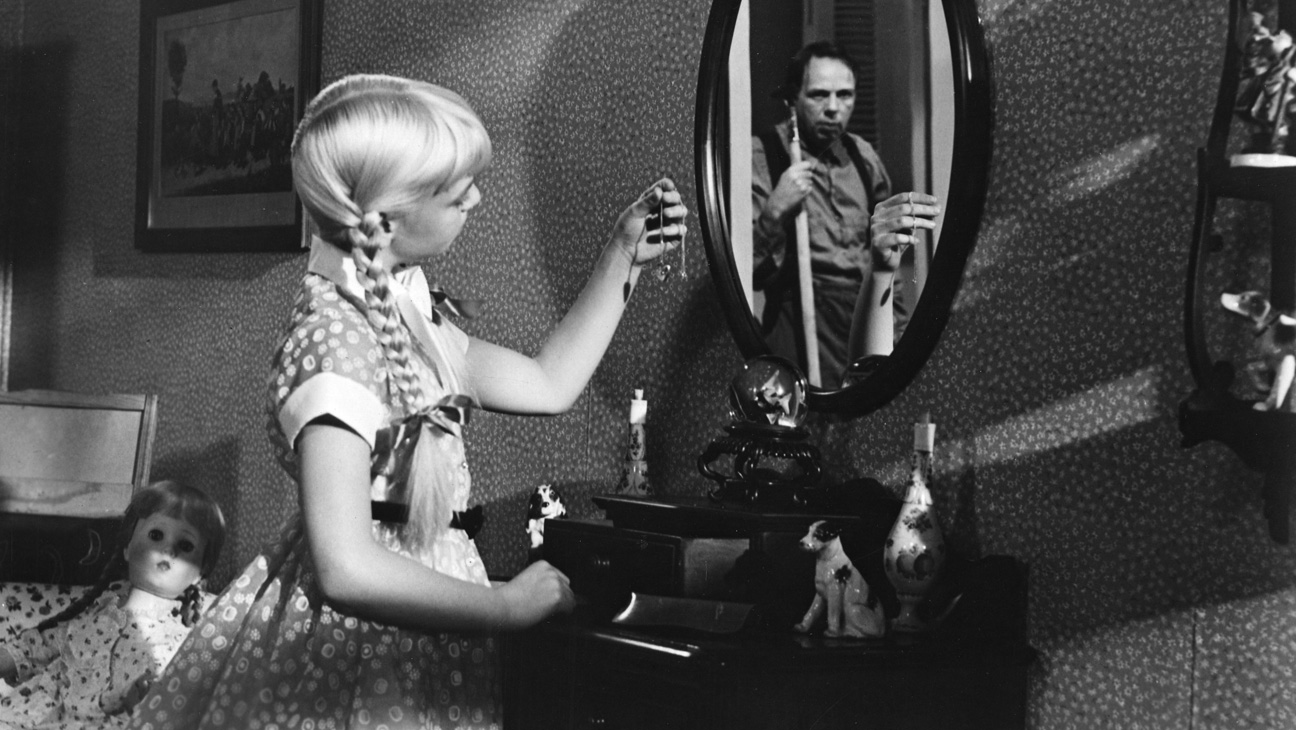

15. The Bad Seed (Mervyn LeRoy, 1956)

An unexpectedly good scenario coming from the 1950s, if not the first then sure to be one of the first movies on child cruelty and criminality, “The Bad Seed” tells the story of Rhoda, an 8-year-old girl with angelic looks and the devil’s soul.

Kenneth, an Army colonel, and Christine are a happily married couple with an adorable daughter who seems to be the incarnation of perfection; neat, tidy and well-mannered, she easily gains the affection and love of adults, even though she is not very interested in relationships with her schoolmates.

Kenneth leaves for his office in Washington and Christine stays with little Rhoda. She accompanies her on a school picnic, talks a bit with the headmaster explaining her the fears she has about Rhoda not having close relations with her peers, and is much of a perfectionist.

And then she leaves, only to learn some hours later that a little boy was drowned and Rhoda was the last person to have any contact with him. Claude, the drowned boy, had won the penmanship medal that Rhoda believed she deserved.

The next day Christine is visited by both the headmaster of the school, who explains the aggressive behavior Rhoda had toward Claude during the picnic and that she is not wanted in the school for the next year. Claude’s mother, who is desperate and drunk, seeks to know what happened to Claude’s medal, as he was found without it.

When Christine finds the medal in Rhoda’s room, terrible suspicions start to rise in her head about who her daughter really is, strengthened by their own tenable thoughts that she is not the natural child of her parents but the adopted daughter of a notorious serial killer.

A chilling thriller that freezes the blood, this film poses the theoretical question about whether our behavior is determined by the environment we grow up in or by genetic predisposition. The scenario defends the idea that some people are determined by their genes in important matters such as criminality, a rather conservative posture that tends to diminish the importance of social factors in the way we act and react.

14. Cracks (Jordan Scott, 2009)

In an elite British boarding school in the 1930s, Miss G is the swim team coach who has created a myth over her past achievements and is adored by her young pupils, especially Di. The arrival of a mysterious, gorgeous Spanish girl named Fiamma will change the fragile balances. Miss G falls for Fiamma, who pushes her back, and she, enraged, gets ‘her’ girls to go for Fiamma. They isolate her, humiliate her, and at the very end, chase her into the woods as if she was a wild animal and hurt her every way they could.

As adolescence is a fragile and unbalanced period in one person’s life, emotions can change rapidly from fear to admiration, and then love and then hate and then all over again. The schoolgirls look at their new schoolmate as a stranger, sometimes fascinated by her storytelling abilities and sometimes filled with jealousy, awe and disgust.

The fluctuation of their feelings goes hand in hand with the manipulative power a charismatic adult has in turning them in the way she mostly wants. Outmost cruelty will be the result of non-acceptance and jealousy, and it will lead to devastation in this bitter coming-of-age movie.

13. Village of the Damned (Wolf Rilla, 1960)

A science fiction horror film of 60’s British cinema, the movie tells the story of a group of unusual children with extra-human powers that were born under mysterious circumstances in a small village of central England.

Out of the blue, one day, the inhabitants of Midwich lose their senses for several hours. Some months after that incident, all the young women of the village give birth to identical children with platinum hair and piercing glances. The children have extraordinary powers, who use them mostly to cause harm to other people.

When the villagers realize how dangerous they can be, they try in vain to get rid of them. Only Professor Zellaby, who once talked in defense of them in an attempt to exploit their endless abilities for good purposes, may conceive a plan to exterminate them.

Cruelty from outer space. Children are normally gentle and sweet creatures. Only a genetic anomaly accounts for this lack of positive emotions.

12. Fat Girl (Catherine Breillat, 2001)

A rather provocative film on teenage sexuality, it approaches cruelty in the way Anais, the ‘fat girl’ of the English title, conceives parental and sibling love, and is initiated to sexuality in a rather perverse and brutal way.

Anais, who is 12 years old, and Helen, her 15-year-old sister, are spending their holidays in a place by the sea together with their parents, a bourgeois couple from Paris who offer their children all the comforts they wish and nothing more than that. Helene is beautiful and attractive and takes pleasure in humiliating her younger sister, who is overweight and intimidated. Anais finds comfort in eating and escapes in her own fantasies about future sexual contacts.

When they meet a young and handsome Italian who flirts with Helene and presses her to have sex with him under the pretext of being in love and wanting to marry her, Anais feels even more unwanted, as she has to accompany her sister to her walks with her boyfriend and stroll around alone. Their clandestine nocturnal meetings, in the same room where Anais sleeps, is a tortuous, cruel experience that will haunt her for a long time.

Anais receives cruelty and responds with indifference in a peculiar coming-of-age movie that was banned in the Ontario Film Review Report for its bold representation of teenage sexuality.

11. Scum (Alan Clarke, 1979)

A harsh movie about the brutality governing the British ‘reform’ system of the 70s – the notorious borstals. It denounces cruelty and violence from the part of the guards and among the prisoners by showing that the one who won’t become cruel will go mad or die.

Racism, rape, violent attacks, a struggle in which the most powerful wins and the weak is doomed. The film, apart from being crime drama, as it is described, could be as well an in-depth study of characters, an inner look at the misfits of class society who end up in a reformatory institution that crashes any human sensitivity there is left in them. Or leads them to suicide.

Marked by very strong and upsetting scenes of violence, it portrays the young prisoners being both victims and ‘headsmen’. Their community is as cruel as the one of their guards. Carlin enters the borstal and soon has to face the brutality of the wing’s bullies. He will work his way to the top of the prisoner heap by violence and, though he doesn’t turn as vicious as his predecessors, he is marked by a cruelty from which he cannot escape. He looks at young Davis, who has just been raped, and he cannot really see him. Cruelty generates alienation.

In an environment shaped by cruelty, every reaction is a dead end. Archer, an older, intellectual prisoner, tries to form his nonviolent way of resistance with no success. His dialogue with the guard who watches him during the Sunday mess, which he doesn’t attend, being an atheist and a vegetarian, is a literature masterpiece that shows how both prisoners and guards are trapped in the same endless loop.

The prisoners’ rebellion, caused by one more suicide, will end up in repression, more brutal punishment and more despair.

10. Au Hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966)

Poetry, a hymn to sainthood found in the most bizarre places, the story of two tender and mistreated beings through the years, as they face inexplicable cruelty by their surroundings.

Marie gets Balthazar, a baby donkey, as a pet when she was a child and they grow up together, loving and caring for one another. She becomes a beautiful but shy young girl who is sentimentally abused by the cruel youths of her village – mostly by her own free will, as she turns down the love of the landowner’s son.

Balthazar is separated from Marie and suffers all kind of maltreatment, a parable of Christ’s way to the cross. Deadly hurt by the same cruel youths who torture Marie, he dies in a field between sheep and dogs, amidst the love of the Divine and its creatures, in a film scene of astonishing beauty and sorrow.

9. We Need to Talk About Kevin (Lynne Ramsay, 2011)

Lynne Ramsay’s cinematic adaptation of Lionel Shriver’s novel is a story spoken by a woman, written by a woman and filmed by a woman. It tries to shed light on one of the extreme social phenomena that ravage American society, that of adolescent mass murderers, by giving emphasis to the mother-son relationship.

Kevin is a cruel adolescent. In the film – and the novel – he is portrayed as a cruel person, even in his childhood and babyhood. Whatever he chooses to do is destined to cause physical and psychical pain to others: his parents, his sister, the unlucky animals that happen to be on his way, his schoolmates and teachers. His cruelty, from the very first days of his life, is quite inexplicable… or rather caused by the dysfunctional relationship he had with his mother from the very start.

Kevin’s cruelty will culminate with an act of incredible violence: trying to show his emotional emptiness and lack of any feelings of love and compassion, he exterminates more than a dozen of his schoolmates and half of his own family, leaving his mother alone to carry the guilt.