One of the most highly polarising auteurs of contemporary cinema, the Hungarian-born writer-director Béla Tarr has nevertheless delivered some of the most resounding films to ever come from Europe. Making nine features in a career spanning nearly four decades, Tarr’s style has definitely evolved over time.

Starting in the Budapest school movement (1972-1984) – often compared to cinema vérité (itself inspired by Kino Pravda) – Tarr made films rooted in social-realism, still including his prominent motifs of repetition, fear, the intergenerational rift, corruption, and the critique of dehumanising politico-economical systems.

Through the years, however, Tarr developed a preference for formalist filmmaking, realising that a composed (artificial) cinematography doesn’t necessitate artificial characters or emotions. In fact, Tarr’s emotional (and some would argue aesthetical) realism seemingly reached new profundity as he grew into his formalistic skin, offering a bold type of realism few others in his field could successfully deliver.

9. The Outsider (1981)

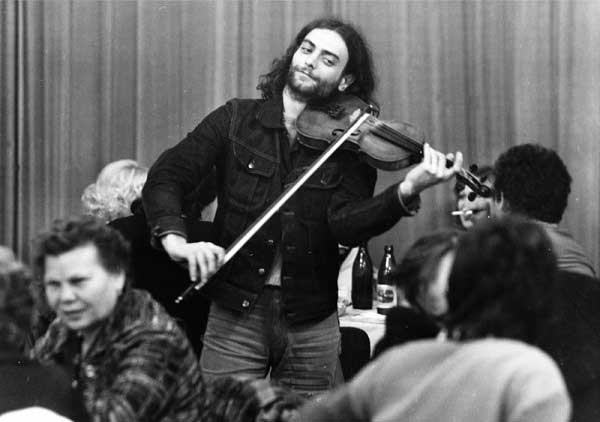

The second of three of Tarr’s Budapest school films, “Szabadgyalog” (“The Outsider”) introduces us to András (played by András Szabó), a disillusioned young violinist inhabiting an absurd world.

This marks Tarr’s first collaboration with his wife-to-be, Ágnes Hranitzky, who would go on to edit all of his future films and receive co-director credits from “Werckmeister Harmonies” onward. It’s also his first film in colour, giving him the opportunity to play with artificial lighting, which he does spectacularly well (especially thinking of the couple’s quarrel in the dance club).

While “Family Nest” and “The Prefab People” are also linked by the motif of degenerative relationships, “The Outsider” focuses on only one of the characters in the relationship – the titular “Outsider”, András. This foreshadows Tarr’s subsequent works like “Damnation”, “Werckmeister Harmonies”, and “The Man from London”, which mostly focus on a singular protagonist’s psyche.

Sexuality, like many elements in this story, is rendered absurd due to its manipulative use when Kata (Jolan Fodor, András’ wife) convinces her husband not to open the door to his brother (Imre Donko) out in the cold night. Even though it’s not purely portrayed as such by Tarr, the motif of sex as manipulation would return in future films.

Needless to say, the film has several things to offer, memorable moments (the story about Beethoven and Goethe), some interesting visuals (the dance club, András “orchestrating”), and the portrayal of a man’s need for obliviousness in a world he cannot or will not process. However, the film is lacklustre in comparison to Tarr’s other works, as it does a better job at setting up his future strengths than developing them.

8. The Man from London (2007)

“A londoni férfi” (“A Man from London”), based on the Georges Simenon novel “L’Homme de Londres” (1934), is the closest Tarr comes to making a film noir. We open on Maloin (Miroslav Krobot), a railway switchman stealing a briefcase full of money at the scene of a murder he has witnessed from afar, subsequently entering a cat-and-mouse game between the original thief and the police, playing ill-effect on his relationship with his wife (Tilda Swinton) and daughter (Erika Bók).

Although the story is told with visual mastery – some of the best in all of Tarr’s works, especially considering the beautiful chiaroscuro – we feel little empathy for most of the characters. Apathy is normally a staple of a Tarr character; in “The Man from London”, however, their torment is not as apparent as some of his other desolate characters.

One could argue, nevertheless, that this reinforces the social critique as it is only due to the characters’ surroundings and way of life that they are apathetic and abrasive to change. This is also why the dynamics of Maloin’s family are so irreparably damaged once there is a break in the social order (the introduction of money); in this we do find some depth to the characters.

Adding to the motif of the corruptive power of money, the fact that it is blood money increases the shame Maloin ultimately feels. The weight he carries is felt during the dinner fight, when he shouts at his daughter for not eating. She stays quiet, and her mother starts arguing with Maloin, who then leaves the table. Only after this does the daughter start eating.

This is also a recurrence of the motif of disconnected relationships, failing due to a lack of communication (as in “Family Nest”). The only other times we feel such emotion from Maloin is surrounding him killing Mr. Brown (in a chilling, non-gratuitous, yet highly effective scene), and the dealings with Mrs. Brown afterwards; however, these emotions are more often projected by the audience than produced in watching the Maloin character.

Nonetheless, the ending remains powerful; the empathy we feel for Mr. Brown’s wife after she is handed money in a meagre attempt to compensate for her husband’s overlooked murder is strong enough to make us feel that our time wasn’t squandered.

7. Family Nest (1979)

“Családi tűzfészek” (“Family Nest”) was Tarr’s debut feature film. While not being a reflection of his later cinematography, it sets up many signature elements we see in Tarr’s preceding work. The film opens with text saying: “This is a true story, it didn’t happen to the people in the film but it could have.” Not only an appropriate opening for his first film, but arguably his entire oeuvre, as it alerts the audience to the emotional realism of his work.

What follows is the journey of Irén (Laszlone Horvath) and Laci (László Horváth), a wife and husband whose marriage is on thin ice. Staying at Laci’s father’s already cramped apartment with their infant daughter proves difficult; as the story unfolds, the father (Gábor Kun), a spiteful drunkard who hates Irén, plots to split the two by insinuating that Irén has been unfaithful. Meanwhile, Laci’s own adulterous behaviour and insecurity, fuelled by his father’s hateful discourse, slowly poison his thoughts.

Tarr’s to-be-recurring motif of the symbiotic relationship between human malice and apathy is displayed in one of his most shocking scenes, which involves Laci and his brother raping a young gypsy girl (who works at the same factory as Irén) as they walk her out after a party at their father’s place.

Although not in style, the essence of this rape scene could be compared to that of Ingmar Bergman’s portrayal of the horrendous act in “The Virgin Spring” (1960) in that the portrayal itself is non-gratuitous, yet the effect produced is appalling. All the more disturbing is that the scene is instantly followed by the same three people (the rapists and the girl) standing quietly together in line at a bar, feigning normalcy, yet we recognise a drowned, powerless torment in their eyes.

Communication is key in “Family Nest”; we see this in the relations that Laci and Irén have with their parents. Laci and his father’s conversation is filmed by panning, showing a passage of ideas; whereas Irén talking to her cold mother is shown in a shot-reverse-shot, underlining the disconnection between them.

Lack of communication, and the fear of opening up to one another, is ultimately what dooms the couple to an unhappy life, leading Tarr to close on them, comparing them to the two chickens on which that the film opened, an allusion to their impetuousness.

6. The Prefab People (1982)

“Panelkapcsolat” (“The Prefab People”) was the third and last film Tarr made with the Budapest school ideology, and visibly uses the knowledge acquired from his previous two features to deliver what is often considered the best of his work from this period. Shifting the viewpoint back from the single protagonist of “The Outsider” to a family once again, we find Férj (Róbert Koltai) and Feleség (Judit Pogány) in an already disintegrating marriage.

We’re introduced to them during an argument. The intense display of desperation from Feleség and apathy from Férj is both jarring and uncomfortable to watch, finally ending with Férj leaving Feleség alone in the apartment. A week later, Férj comes back as if nothing had happened. Feleség cries as she tries to understand how he could do this, and life goes back to normal. Later on in the film, they have again an eerily similar fight.

The prominent motif in all this is recurrence, a constant back-and-forth between the characters. Tarr depicts droning lives – from the women reminiscing in the beauty parlour, to idle drinking, to the factory workers literally droning around in their chairs – whose only patterns are a series of backs-and-forths.

Férj’s obliviousness against Feleség’s volatility constantly push them away from and back to each other in a superfluous cycle, under the ominous governance of “a kind of society.” In Férj’s monologue to his son, he explains the different types of failed human governances over history, both political and economic; this type of social critique is to be seen again in most of Tarr’s future work, especially “Werckmeister Harmonies”.

The critique of capitalism is visually represented in the final scene, right after a fight, where the couple goes to a store together to buy a washing machine, once more trying to continue to live life under a hood of normalcy. They ride home at the back of a pickup truck, next to the washer. The absurdity of the situation warrants a final, three-minute long shot, underlining the void with which we leave the characters.

In “The Prefab People” we witness the beginning of one of Tarr’s most prominent motifs. Eternal recurrence is a philosophy stating that the entire universe, and all life within it, is a series of repeating, never-ending combinations; this was also one of the core concepts that Friedrich Nietzsche endeavoured to examine in his oeuvre, with Nietzsche becoming a part of the premise of “The Turin Horse” in 2011.