We humans have a peculiar obsession with sending things into space. Be it photos, food, video games, books, novelty items, peoples’ ashes, iPods, we’ll eventually send one of everything into space.

The only movie known to have been sent into space is The Day the Earth Stood Still, a decision that makes sense when you think that maybe, out there in the big star-riddled black, some kind of intelligent life might see it. But do we really want possible aliens to see a sci-fi film that resonates more with humans than whatever might be out there? Intelligent life debate aside, it can be argued that movies would be a great way to leave a mark by humanity in the universe.

For whatever future races to come later down the road, how would we want to show what human life was like? There are many films thatcould be sent into space, but so many films show individual perspectives on Earth and humanity, it’s difficult to choose just one film that can best summarize life on Earth.

Well, how about three? Enter… the Qatsi Trilogy. This is director Godfrey Reggio’s unrivaled trifecta of experimental cinema, and it has never been quite equaled in either its intentions or its end results.

This trinity, consisting of 1982’s Koyaanisqatsi (Life Out of Balance), 1988’s Powaqqatsi (Life in Transformation), and 2002’s Naqoyqatsi (Life as War), continues to amaze cinema’s most adventurous fans. Stoners smoke up in basements to the same images that film students laboriously study and dissect and analyze with excruciating detail.

The now legendary cult documentaries are the kind of films whose titles linger on the tongues of cinephiles who appreciate their psychedelic beauty or at least have claimed to have ‘understood’ them. Reggio himself has become forever associated with these films, and people like cinematographer Ron Fricke and composer Philip Glass have become widely praised thanks to their vital and unforgettable contributions.

The first film, Koyaanisqatsi, remains probably the best of the trilogy, perfecting the elements that have become legendary and instantly recognizable within the annals of cinema.

Powaqqatsi is less ambiguous but more ambitious, showing the increasing influences of technology and industry in the third world. It’s a far more global film, choosing not to look at a society that has accepted these changes wholesale, but numerous societies struggling to come to terms with such invasive and omniscient realities.

The final film, the polarizing Naqoyqatsi, is most likely the most nihilistic and cautionary. Instead of warning us, it chooses to show the world in its current, part technological part natural state, and urges us to imagine a world where the line is blurred and we ourselves have become part of a global machine.

These films, while slowly becoming dated with each passing year, exemplify all aspects of human life, and helps to show how we have involved from a simpler existence and evolved into a species that advanced our technology to incredible degrees. Its shows us in relation to technology and nature and tries to make sense of this confused relationship.

Below are five reasons why the Qatsi Trilogy should be shot into space for intelligent life, if it exists, to find and view so that they might understand the madness that is (or was) humanity.

1. The Examination of the Human-Technology Relationship

One the Qatsi trilogy’s most undeniable themes is the relationship by which humans and of all forms co-exist. To accurately address and portray such a unusual agreement between two vast extremes; the organic and the artificial collaborating in their advancements in life. The first film, Koyaanisqatsi, introduces this theme in spades.

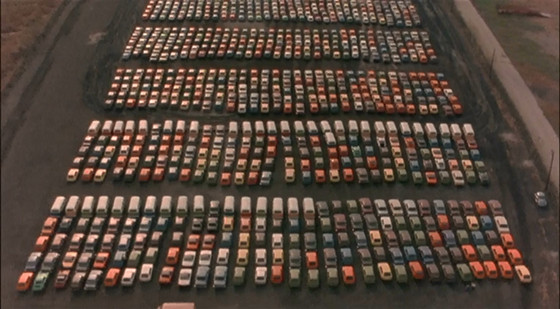

It focuses, primarily, on contemporary North American society (contemporary for the late 70s-early 80s, that is) and shows a society in perpetual yet almost meaningless motion: people and cars zipping along at absurd speeds through the streets of Los Angeles going nowhere, prosperity co-existing with poverty, the creation and further advancement of a world that no longer exists within the unpredictable and organic realm of nature, but by the rigid and calculated world of technology.

One of Koyaanisqatsi’s most memorable moments involves an overhead view of Los Angeles which gradually transforms into the intricate wiring of a microchip, a possible suggestion of our modelling of our lives based more on technology rather than nature: we are becoming slaves to structure and stringency. Powaqqatsi shows a world struggling to accept these changes outright, while Naqoyqatsi theorizes a kind of technocratic reality, one beyond a return to total nature: complete fusion of the biotic and abiotic.

Cinema is notorious for presenting us with usually extreme reactions to technology. Genre filmsare particularly known for their depictions of rogue tech antagonizing human protagonists. But the Qatsi trilogy doesn’t side with either position on the matter. Reggio portrays it as both destructive and constructive, building up our world to glorious heights while also damning us to future disasters as a result of our recklessness.

It seems that Reggio’s intention was to open the floor, as it were, to a universally open discussion to the balance of nature and technology in this world. To open such a wide-ranging topic to everyone, one must not allow unneeded biases to influence what is being presented.

To show both sides of this relationship and its place in the modern world is already a difficult topic, but the Qatsi trilogy allows for such heavy themes to be easily digested through the power of cinema. Not only that, but each film explores a different aspect of the topic, allowing the discussion to go beyond just a surface level conclusion.

2. The Lack of Character and Plot and the ‘Pure’ Nature of the films

Cinema may have been built from grand narratives and dashing characters, but more often than not, these typically crucial elements can distort one’s view of the world. Wall Street can be shown as an exciting world of big deals and bigger money, a university frat house depicted as the true party in life, and a trip to Paris can give the impression that it really is the city of lights and candlelight romances.

When the world is filtered through the minds of screenwriters and directors, distortions in perception can occur which leaves the audience grossly misinformed about certain realities in this strange world. Actors rarely portray their characters as realistic human beings, as people who would think or act as they actually would in the real world, and typically perform as idealized versions of what audiences might aspire to be.

That is where the Qatsi trilogy is seen as a breath of fresh air: the films are adamantly plotless and lack any main character. It also refuses to either canonize or demonize humanity, even if it could be argued that the human race is the main character of the films. No one individual is placed centre stage in any of Reggio’s films, and by doing so, he gives the films a more universal and inclusive view of the world. They show more of humanity as a complete and varied whole.

Because of this, the film has no altered perspective, no manipulated worldview that would be connected to a single character. The non-narrative approach also allows for Reggio to merely show the people and places depicted as naturally and real as they are outside of the silver screen.

This lends itself to its ‘pure’ feel, with an atmosphere that’s not voyeuristic but still presenting of a window into modern human society. All you see is real and genuine, no organized crowd sequences, no dialogue or voiceover, nothing to influence how the audience sees the images. This philosophy is most evident in the first two films, but Naoyqatsi, with its highly digitized and manipulated images, continues this trend in a different direction.

The third film still has no narrative elements, but what it depicts is more hypothetical and cerebral, choosing to show a world in the throes of a complete technological conversion. However, the film still objectively depicts the reality of a tech-ruled society without a character or characters for us to latch on to for the sake of relatability, as well as lets the insane and unpredictable nature of life mostly speak for itself.

While this approach is not new (see Dziga Vertov’s revolutionary Man with a Movie Camera), The Qatsi trilogy was able to take this radical cinematic philosophy and still get across themes and concepts without typical narrative devices. A commendable feat that, to the trained eye, is still impressive to this day.

3. The Lack of Religious or Ideological Bias

When one first witnesses the psychedelic nature of the Qatsi trilogy, it wouldn’t be unthinkable to imagine a jaded viewer letting out, in a pseudo-stoner drawl, ‘what does it mean, maaaaan?’ Other times, said viewer might just throw their television out the window as a result of their frustration. The Qatsi trilogy never provides explicit clues or explanations as to what they are trying to convey, forcing audiences to pour in double the effort in finding any meaning in these images.

Instead of lowering itself to hand-holding or blatant symbolism, Reggio presents us with images and scenes that are ambiguous enough to lead the viewer to their own interpretations. Films become elevated to some a lot more when they become universal and can take on many different interpretations, each one unique to every singular viewer.

Some ideas may overlap, but if a film can elicit such personal and original responses from every person who watches it, the potency of the film is proven and becomes one of its defining features, something that makes it far more enduring and helps keep the film constantly refreshing for all future viewers.

No film in this collection subscribes to any particular ideology or religious belief or culture. Reggio has intentionally given us images that, in parts, seem pointless and random and lacking of any meaning to the overall film. They aren’t influenced by any kind of agenda or idea; Reggio’s perfectly content with not letting any outside influences take over. This perceived lack of theme and influence allows for an open-minded approach. Its lack of cultural influences makes for a universal viewing experience.

There aren’t any jokes or references that would make sense to only one people. Everyone can make sense and understand what’s being shown here in these films. Nothing shown here has any basis in any human ideals and beliefs, which makes the films far more relatable among all audiences. It can also help people who might have very different opinions about movies, or even art in general, appreciate the films across the board.

4. The Equal and Objective Depictions of Nature and Technology

Koyaanisqatsi and Powaqqatsi both show a world in transformation and radical change, with technology and nature intertwining at incredible speeds, the former showing a seamless transition in some cultures and the latter showing places that continue to dig their heels in for their traditions and cultures.

Naqoyqatsi shows a hybrid world in which technology and nature are no longer separate entities, but one and the same. While any semblance of bias most likely would show itself in the third film, overall the film seems to show both the natural and technological aspects of the human experience in equal measure and as one.

As we as a race continue to hurdle towards that uncertain future, the prevalence of technology continues to integrate itself into the world we inhabit. Some welcome it, others fear it, but it cannot be denied that what has become such an integral aspect of our lives is not only evolving beyond our wildest dreams, but is slowly starting to infuse itself within the natural aspect. This is where the trilogy really takes off.

In Koyaanisqatsi, technology is not singularly shown as some invading force nor the saviour to our modern problems. It’s presented more in a real-world sense, something we live with and don’t always pay attention to. It’s very real within Reggio’s lens, but so is nature. Nature will always exist, as long as the earth continues to exist.

Koyaanisqatsi is both weary and optimistic of this balance, as evident by its flurry of scenes showing a fast-living techno-society interspersed with calming, awesome landscapes of the Arizona badlands and vast forests and lakes.

Powaqqatsi follows a similar approach, this time expanding beyond simply North America and takes it to a global stage, contrasting the traditional and the modernized. Against images of meditators at the Ganges River are children watching the barrage of neon lights flash across car windows, to name but one good example. It never denounces nor praises technology’s place in the third world, but it lets the viewer come to their own conclusions.

Naqoyqatsi is the most difficult to discuss because its goes in such an unusual direction. Instead of exploring the balance between nature and technology and showing an objective perspective on them, Naqoyqatsi heads in more hypothetical territory, never showing a clear-cut divide between tech and nature.

Through absolute digitization of real-world images, it’s a far more conceptual film than the others, showing more or less a radically evolved future; it wouldn’t be too crazy to say the film takes place after the events of the first two, showing a world far more violent than the relatively peaceful earth shown in Koyaanistqatsi and Powaqqatsi. Regardless, it still shows technology and nature as they are, however this time, technology has overtaken nature, creating an unsettling distortion of the organic.

5. The Utilization of Special Effects and the Purity of Imagery

With cinema being a perpetually evolving art form, with computers being utilized to generate and animate wonderous and perplexing images of the inexplicably fantastic. It seems CGI is inescapable, regardless of genre or director or country of origin. Not only has practical effects become a valuable commodity among today’s films, genuine in-camera effects and an expert photographer’s eye have become more appreciated than ever.

The Qatsi trilogy, especially in Koyaanisqatsi and Powaqqatsi, favours this organic approach in spades. While Naqoyqatsi is an entirely different beast, it’s the first two films that feature no fantastic or unrealistic images, calling upon the natural beauty of the earth instead. Such purity and confidence in what’s being shown is a rare occurrence these days. But let it be known that such magnificent views are not merely Reggio’s doing.

Behold, Koyaanisqatsi and Powaqqatsi’s cinematographer extraordinaire, Ron Fricke. His work is reflective of his obsessive handling of such an abstract cinematic concept, both within Reggio’s trilogy as well as his own solo works, Cronos, Baraka, and Samsara.

From dizzying time-lapses of the L.A. freeway, to multi-layered visions of third world labourers deep in muddied excavations, everything is imbued with a sense of etherealness, giving images we’ve seen all our lives a new sense of wide-eyed wonder and fascination.

Fricke would achieve international acclaim for his work on the first two films of the Qatsi trilogy, has gone on to have a successful career directing films in the similar vein to Reggio’s trilogy, as well as acting as cinematographer on others (he helped create the volcanic planet of Mustafar for Star Wars Episode III by filming an actual volcanic eruption in Italy).

However, Naqoyqatsi is not worried about the beauty of earth. As discussed before, the black sheep of the Qatsi trilogy has chosen its battles with technology and the future, and it can be described as theoretical more than anything else. Let it be known, however, that Naqoyqatsi has its place with the previous films. The images here are not original for the most part, as we have seen many of these images before, but never in such a profound and radical way.

Filtered through quick-cutting montages and incredibly layered editing and visual manipulation, Naqoyqatsi’s depiction of the future is achieved through its restructuring of images we see every day into technological nightmares. But, the purity of these images remains intact, for you see, the images are still real. They may not be as breathtaking as those in Koyaanisqatsi or Powaqqatsi, but here, they are changed beyond recognition.

That what was once seen as mediocre and average has been transformed into the inevitable and the dystopian. Naqoyqatsi shows us things that are still true to the world around us, but uses them not to demonstrate what surrounds us now, but what will eventually encircle the human race, leaving us no escape from the grand amalgamation of nature and technology that awaits us.

Author Bio: Mason Chennells is an aspiring writer and life-long cinephile living in Alberta, Canada. He usually can be found hiding out in a local theater or library when he’s not writing. He’s also an amateur musician, artist, and novice Esperantist.