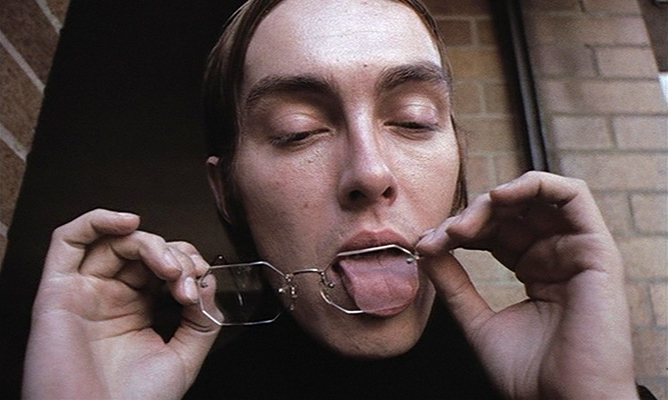

“My conceit was that my films would be, in the world of film-making, these emergent creatures that would be unprecedented and not able to have been predicted.”

– David Cronenberg

When Canadian director David Cronenberg was a child, he wanted to be a scientist. By the time he was in university, inspired by writers such as William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard, he knew that he was going to be a writer. Surrounded by the burgeoning culture of student film-making, he found himself drawn inexorably to the movie camera, with which he would eventually carve himself a place in the history of cinema.

He made his name in the horror genre, crafting unique and disturbing visions of body-oriented horror. A strong atheist in life and expression, his monsters didn’t attack us from supernatural realms: they grew within us, from us. It is this embracing of the flesh that made his early films stand out from the rest. Over time his work has mutated and evolved like his protagonists, on whom he experiments, and manipulates, like one of the mad scientists in his bizarre imaginary institutions.

David Cronenberg has always been a scientist: a scientist of the imagination.

1. Early Shorts: Transfer (1966) & From the Drain (1967)

“An analyst has to dip his fingers into the murky, forbidding, scummy aquarium of the sick mind, Ralph!”

– Doctor, Transfer.

Transfer marks Cronenberg’s first experiment in film-making. A psychiatrist, referred to only as “Doctor”, is living alone in a snowy field surrounded by pine woods, his furniture spread across the freezing landscape. When a former patient named Ralph appears, the Doctor is distraught. Ralph has been following him obsessively, and now he has discovered the Doctor’s hiding place. What follows is a over-dramatic and hilarious dialogue between the two, as Ralph declares his love and dependence on his analyst.

Transfer is an absurd comedy about the dangers inherent in the relationship between an analyst and a patient, about obsession and dependence. It deals with the fragility of the mind, and it illustrates the greatest inevitable weakness of psychoanalytical relationship: the fact that the analyst is another human.

In From the Drain, two men sit in a bathtub in a halfway house for the veterans of a war now over. They talk about how things are changing: the biology of plants and humans. After they talk a vine springs from the drain and strangles one of the men: some agency, no-longer entirely human, is killing the veterans of the war.

Cronenberg describes From the Drain as a Samuel Beckett sketch. A faint echo of the Irish master is undeniable, but the embryonic form of what would become Cronenberg’s major themes are evident here too: paranoia, shady conspiracies, and the changing nature of humanity in an ever changing world.

2. The Experiments: Stereo (1969) & Crimes of the Future (1970)

Stereo & Crimes of the Future are Cronenberg’s first two feature-length films, and mark what he has called his “avant garde” stage. Shot and edited largely by Cronenberg himself, in and around university campuses, both films feature experimental styles and techniques that are more the product of learning-by-doing than the influence of the avant garde film-making of the time. The result is a pair of genuinely unique and hermetic cinematic visions.

In Stereo, seven young adults submit to an experimental brain surgery performed at the Canadian Academy for Erotic Inquiry, which, according to the theories of parapsychologist Luther Stringfellow, will make them capable of telepathic communication. The theories prove to be correct, and the seven subjects are tested, manipulated, and eventually separated with tragic results.

In Crimes of the Future, an infection named Rouge’s Malady has wiped out the entire population of females past puberty, a disease spread by cosmetic products. Dr. Antonie Rouge, the dermatologist who discovered the disease has disappeared (possibly a victim of the malady himself). His disciple, Adrian Tripod, has taken over the management of Rouge’s clinic The House of Skin, but is lost without his mentor. His desperate search for answers lead him into strange institutions and organisations, and into the midst of a disturbing conspiracy.

All of the elements that would come to define Cronenberg’s unique brand of cinema begin with Stereo and Crimes of the Future: unusual institutions, experimental therapies, imaginary diseases, shady conspiracies, and the exploration of mind and flesh.

3. Rabid (1975)

Following the success of Cronenberg’s first commercial feature Shivers, Rabid tells the story of Rose, accidental vampire and mother of a deadly new plague. Rose and her boyfriend crash their motorcycle not far from an experimental institute called the Keloid Clinic.

With Rose badly wounded, Dr. Keloid performs emergency plastic surgery on her digestive system, but his unorthodox methodology, utilising experimental ‘morphogenetically neutral’ matter, has unexpected results. She grows two phallic organs which emerge from her arm-pits with which she uses to feed on the only thing she can now digest: blood.

Afraid and confused, she escapes the institute to satiate her new-found thirst, but every person she feeds on is infected with a disease which makes them mindless and rabid. The infection spreads and becomes epidemic.

Rabid was co-produced by Ivan Reitman (Ghostbusters, Kindergarten Cop) and starred porn star Marylin Chambers as Rose. Inspired more by the concept of morphogenetically neutral flesh than by vampirism, Cronenberg watched a plastic surgeon operate for inspiration.

Upon release, Rabid did well for a low budget horror film, but attracted criticism from feminist commentators who accused Cronenberg of representing female sexuality as predatory. It wasn’t the first time his work would be attacked by interest groups on either side of he political spectrum, nor was it the last time.

4. The Brood (1979)

The Brood is arguably Cronenberg’s most personal film. It was written during a burst of energy he would later describe as “almost automatic writing”, when he was supposed to be writing another script entirely, The Sensitives (which would later evolve into the cult hit Scanners). Drawing from the pain and anguish of a failed marriage and a bitter custody battle over his daughter, The Brood tells the story of a similarly failed marriage, and a little girl named Candice who is torn between her father and monstrous mother.

In a weak emotional state, Candice’s mother Nola has checked in to the Somafree Institute, under the care of the charismatic psychotherapist Hal Raglan (played by veteran actor Oliver Reed), who uses an experimental method called psychoplasmics, encouraging his clients to release suppressed emotions through physiological changes in the body.

When Candice visits her father Frank after spending time with her mother, he discovers bruises and sores, and fears the worst, and informs Dr. Raglan that he intends to end Nola’s visitation rights. Worried about exactly what is being practised at the Somafree Institute, Frank investigates and discovers that Nola’s psychoplasmic treatment has had some monstrous side effects that have put himself and his daughter in great danger. Nola has manifested her rage in a brood of drone-like children, grown from tumorous flesh.

5. Videodrome (1983)

“Censors tend to do what only psychotics do: they confuse reality with illusion.”

– David Cronenberg

As a film-maker concerned with extreme imagery, Cronenberg is no stranger to the fears varying interest groups harbour about the effects of violent and sexual imagery. Staunchly anti-censorship, he resists self-censorship and has fought against enforced censorship for most of his career, with varying success. Videodrome could almost be interpreted as a snide reaction to those who demand censorship: a play on their own irrational fears.

Videodrome follows the transformation of a man into something more. Max Renn (played by James Woods), runs a UHF television station which broadcasts mostly soft-core porn and violent movies. In search of new material to broadcast, his attention is turned to the titular Videodrome: a mysterious broadcast which seems to feature the torture and eventual death of anonymous captives.

Teaming up with Nicki Brand (Deborah ‘Bondie’ Harry), a talk show host fascinated and aroused by the imagery in Videodrome, Max investigates the broadcast, and learns of the twisted theories and practices of psychiatrist and sadomasochist Professor Brian O’Blivion. His naive quest for new images propels him head-first into a surrealistic and hallucinogenic underworld in which the line between television and reality blurs, and ‘new flesh’ is born.

Ironically, given its premise, Videodrome was mutilated by the censors, who objected not to the graphic violence but to a scene in which we briefly see a dildo on a screen being broadcast on Max’s trashy station. Violence, torture, and mutilation aren’t so bad it seems, but civilisation might crumble if we were to see a dildo in an R18 movie.