The EON-produced James Bond series is the third highest grossing film franchise of all time, and the highest not to feature superheroes or depressive child wizards. Six actors have led 24 screen adventures over half a century, while Bond’s outrageous, heroic escapades have left an international trail of property damage, reconsidered physics and awestruck bystanders.

This is not a list of my favourite Bond movies. Nor is it a list of the greatest individual stunts, which would have to include the corkscrew car jump from The Man with the Golden Gun and the Union Jack parachute leap that opens The Spy Who Loved Me (a stunt suggested by one-time Bond George Lazenby).

Instead, this is a celebration of the series’ sustained action scenes which, from the very beginning, have been a central and innovative component of the formula and a notable influence on the genre itself. The quality of the Bond movies may be inconsistent, but the set pieces, from concept to execution, show a relentless ambition and a dedication to putting on a good show.

10. Bond vs the Volcano in You Only Live Twice (1967)

You Only Live Twice is arguably the point where the series began to collapse under its own formula. In the first of his three final appearances as Bond, Sean Connery looks bored with the abundance of gadgetry and rice paper-thin plot. But it’s a fast, spectacular romp, and demonstrates why the formula was so successful in the first place.

This is the one where Bond is made up to look Japanese so that he can go undercover in a remote fishing village and pretend to marry a local woman. Not quite as offensive as Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, but a little more ridiculous given that the reasons are dubious (can’t he just hide in a fruit cart or something?) and the make-up, perhaps cutting edge at the time, is not quite cutting edge enough to make Sean Connery look like a Japanese fisherman. Because he is Sean Connery.

Thankfully, the film seems to forget all this by the time Bond and his fake bride Kissy (Mie Hama) go looking for SPECTRE’s secret rocket base and find it inside a volcano. Bond sneaks inside while Kissy fetches an army of machine gun-toting ninjas for backup.

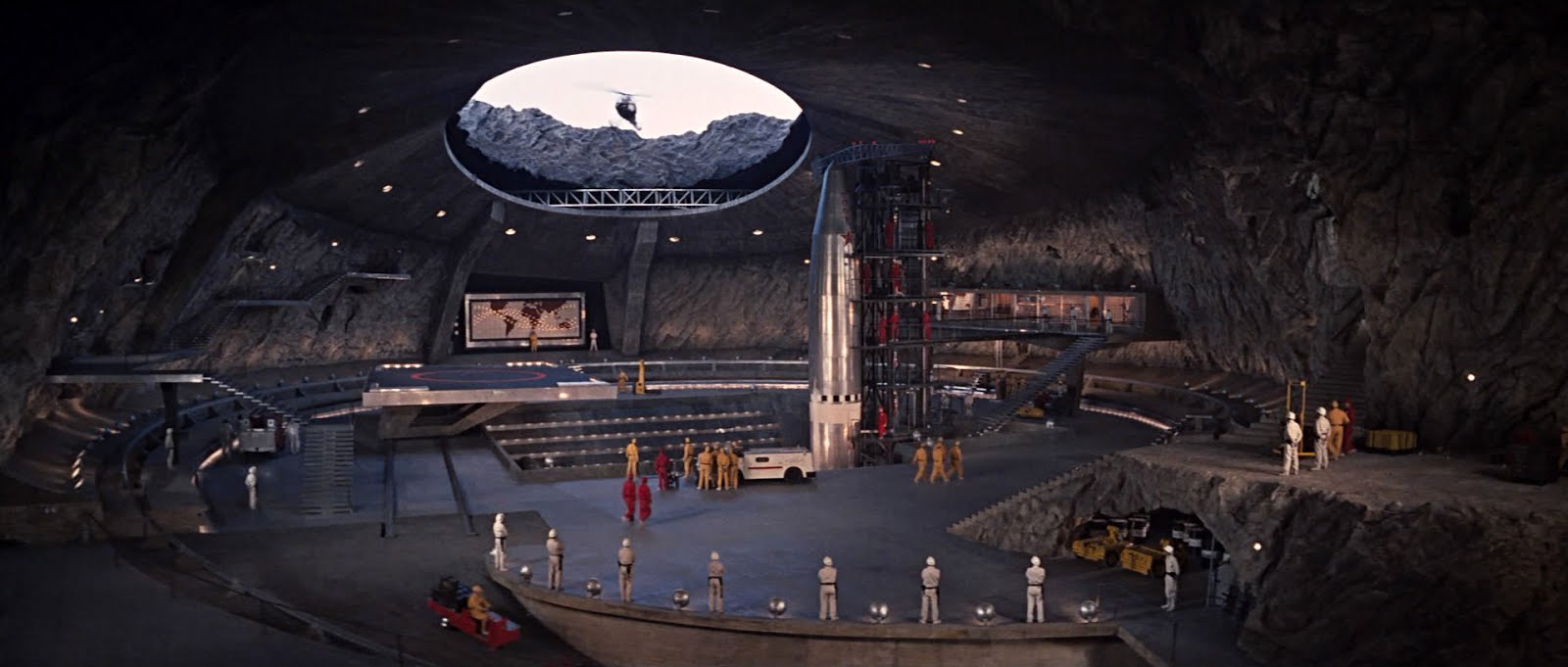

The storming of the villain’s lair became the default climax for Bond movies, but You Only Live Twice set the standard. It’s a lengthy action scene built around a huge, intricate set (including a monorail, helicopter pad, launch tower and piranha tank) with opposing forces in colour-coded uniforms and, naturally, a self-destruct button.

The armed assault is a Sturm und Drang backdrop to the battle of wits and witticisms between Bond and arch nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Donald Pleasance). But there’s a clear structure, with the good guys trying to break into the control room and Bond eventually brawling with bodyguard Hans (Ronald Rich) over the piranha tank – a fracas which ends as you might imagine.

The film’s space-based visual effects have not stood the test of time (2001: A Space Odyssey was released only ten months later) but Ken Adam’s full size hollow volcano is still an awesome spectacle. It’s the most iconic set not only of the Bond series, but of all Adam’s work – which includes Dr Strangelove and Barry Lyndon. Adam would later build the biggest soundstage in the world for the comparable battle in The Spy Who Loved Me, a set which was lit by Stanley Kubrick himself.

9. Through the Ducts in Dr No (1962)

Dr Julius No (Joseph Wiseman), the SPECTRE-sponsored megalomaniac with metal hands, becomes the first of many Bond villains to shut the superspy in a room with two exits but only secure one of them.

Bond infiltrates Dr No’s island headquarters and finds himself in an artfully-furnished subterranean labyrinth with the titular madman as his courteous, sadistic host. After canapés and a summary beating, Bond wakes up in a small cell with a door and a ventilation grille. Rather than, say, meditating on the existential horror faced by a man with metal hands, Bond quickly smashes through the electrified grille and pokes himself into the duct.

Strangely, he doesn’t try the cell door.

From Alien to Die Hard to Mission: Impossible, the crawling-through-the-vent scene has become an action/suspense staple – but this is the original, and still one of the most elaborate examples. Bond is tormented by various obstacles including a rush of water, burning metal, steam and electric shocks.

In Ian Fleming’s novel, the duct system is explicitly a booby-trapped endurance test for intruders. Those lucky enough to survive end up in a rockpool with a giant squid – one of the few times that the source material was crazier than its adaptation.

In the movie, the ducts deliver a bruised and battered Bond to an empty room, and their overall purpose is ambiguous. Dr No’s architects may have simply cut corners by designing a single conduit to carry air, heat, water and a live electrical current.

In a series full of big-scale action, pioneering aerial, vehicular and aquatic stunts, record-breaking explosions and gargantuan sets, these more intimate suspense sequences are often the most effective. This one is a showcase for Connery’s physical grace – he’s just as compelling in the silent procedural scenes as he is growling provocative repartée.

Arachnophobes who read the book after seeing the film may be relieved to find that, in an earlier sequence, Fleming has a murderous centipede slipped into Bond’s bed instead of a spider. Those readers should probably skip Chapter 17, “The Long Scream”, in which Bond, making his way through the ducts, comes upon an entire colony of tarantulas and is forced to stab them to death one by one.

8. (tie) Esprit de Corpse in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

Optional Extras in The Living Daylights (1987)

The Aston Martin DB5 is a work of art and Goldfinger is a better film. But with respect to the 1963 template, these are the two best car chases of the series.

In one of the all-time great marketing coups, Lotus PR man Don McLaughlan parked a prototype Esprit outside Pinewood Studios and won the producers’ hearts. In turn, the Sardinian mountain roads showcase the supercar’s revered handling – Lotus test driver Roger Becker outperformed the stunt team and was quickly drafted in for his skills.

The villains appear and are dispatched in quick succession, from the motorcyclist with a torpedo sidecar to the Ford Taurus full of henchmen to the attack helicopter piloted by sexy tour guide Naomi (Caroline Munro). The momentum is troubled by comic interludes – seeing Jaws (Richard Kiel) survive an unlikely car crash is a slow beat – but Naomi’s murderous flirtation with Bond (Roger Moore at his best) is a playful touch.

When Bond runs out of road he drives the Lotus straight into the sea, where the car transforms into a submarine. Only a sleek sports model like the Esprit could get away with this. But the sequence doesn’t end there – after the coldly protracted sea-to-air rocketing of Naomi’s helicopter, Bond pilots the Esprit to the villain’s underwater lair and foils an attack by various frogmen and battle subs.

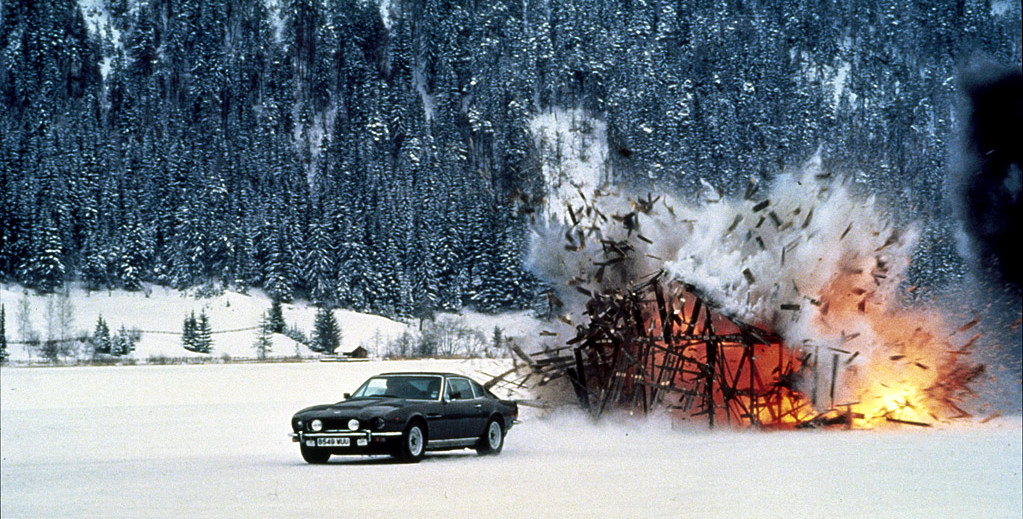

When Timothy Dalton replaced Moore in 1987, Bond’s loyalty returned to Aston Martin and scored a gorgeous V8 Vantage packed to the grilles with artillery. Bond takes it “out for a quick spin” which of course means driving to Bratislava to rescue/seduce cellist and amateur sharpshooter Kara Milovy (Maryam d’Abo) and then spirit her over the border to Austria with the police and army in pursuit.

The sequence builds like its counterpart in The Spy Who Loved Me, deploying the on-board gadgets in order of increasing spectacle. But this is a Dalton film, so after he turbo-launches the car into a snowdrift, it’s a write-off. He hits the self destruct button and takes off down the mountain with Kara, using the open cello case as a makeshift toboggan and her Stradivarius as a rudder.

Sadly Moore never got to drive an Aston Martin, although he did jump over a broken bridge in an AMC Hornet, careen down a serpentine olive orchard in a Citroën 2CV, evade German cops in a stolen Alfa Romeo GTV6, and tear through the centre of Paris in an indestructible Renault 11 taxi.

7. Rock Climbing in For Your Eyes Only (1981)

One of the most average Bond movies was nevertheless singled out for praise by the Patron Saint of Cinema himself, Robert Bresson. “It filled me with wonder beause of its cinematographic writing,” he said. “If I could have seen it twice in a row and again the next day, I would have.”

The film has plenty of action, including an extended Alpine chase with some of the best ski stunts of the series, and a tense underwater battle with an armoured submarine. But the palm-sweating highlight is more straightforward – a literal cliffhanger.

In a fresh conceit, the villains’ lair is a monastery perched on one of the monolithic Meteora rock pillars in Thessaly, Greece. The only way to break in is for Bond to climb 500m up the sheer wall and traverse an overhang, securing his rope with carabiners along the way. The tension is already high as he quietly taps his supports into the rock and disturbs a white dove, attracting the suspicion of the bad guys at the top (who may be expecting Chow Yun-Fat).

When Bond reaches the summit, a commendably dedicated henchman not only kicks him off but then climbs down after him to make sure the job’s done. As Bond dangles beneath the overhang like a startled spider, the villain takes a hammer to the last three carabiners.

Bill Conti’s score drops off the soundtrack here, leaving only the metallic tap-tap-tap as percussion. In a neat climbing trick, Bond forms a makeshift prusik with his bootlaces and inches his way back up the rope – but as each carabiner is knocked free, there’s a little more rope for him to climb.

For Your Eyes Only was intended as a gritty return to earth after the excess of Moonraker. With its remote control helicopters, gadget-packed attack subs and Margaret Thatcher mini-sitcom epilogue, this is only gritty in a relative sense. But the rock climbing was cinematic enough to tempt Robert Bresson back for a rewatch, and is one of the most purely suspenseful scenes of the series.

6. The Pre-Title Sequence in GoldenEye (1995)

The world changed in the six years since Timothy Dalton keyboard-controlled a dot matrix Acorn in Licence to Kill. The Berlin Wall came down, Windows 95 came out, the Bond franchise was caught up in a legal dispute and the high-tech espionage vaccuum was effortlessly filled by Sneakers, Patriot Games and True Lies.

Bond’s relevance has been a thematic concern ever since, first in the wake of the Cold War and now in the era of WikiLeaks, electronic surveillance and drones. It’s an understandable preoccupation, but redundant. Fleming created SPECTRE so that Bond would have a neutral post-Cold War enemy, and there are plenty of freelance maniacs, evil industrialists, assassins, gangsters and drug lords throughout the novels and films.

Pitching his take on the character midway between Moore and Dalton, Pierce Brosnan is introduced breaking into a Russian chemical plant located either beneath a dam or on top of a mountain, depending on which exterior shot you believe. Geographic oddities notwithstanding, this is one of the strongest prologues in the series, bookending the vignette with two high-concept stunts.

Bond enters the plant by bungee jumping from the 220m-high dam, and leaves by motorcycle-launching himself off a clifftop runway in pursuit of a pilotless plane, then catching up with the plane in freefall, taking over the controls and flying away. The physics-defying payoff drew applause from cinema audiences, and the bungee stunt is now a Union Jack parachute-style classic.

The pre-title adventure fully establishes the decadent, suave, irreverant new Bond (his first close-up is upside down in a toilet) and stealthily sets up his relationship with the movie’s main villain – double agent Sean Bean, cementing his reputation with two separate death scenes.

By setting the sequence in 1986, the filmmakers neatly bridge perestroika and glasnost, and the fallout of the Cold War provides a timely backdrop for the rest of the story. But if GoldenEye’s mission was to convince the 1990s audience that Bond was still worthy of attention, it was achieved not through considered politics but by thrilling us with some good old fashioned spectacle.