As the 1980s dawned in the cinematic world it would turn out to be, to paraphrase Dickens, the best and worst of times. Though the era of expansive thought and experimentation looked to be over and many a great master of European cinema ended or wound down their careers, there were still some golden moments in that decade. However, not only was that earlier time ending but a new day was arriving which held promise but which would exact a steep price for all of the gifts it would bestow.

Though the concepts of the VCR (video cassette recorder) and what would become known as cable television had been in the creative minds of those who would help to bring those entities to eventual practical life for decades before the fact, the 80s would prove to be the moment for both ideas.

Though both the VCR and cable had begun their practical lives in the 70s, the public finally caught on to both movements by the mid-point of the following decade and the entertainment world would never be the same.

Thanks to the manufacturers of videocassettes finally realizing that films which were considered fit for niche audiences and cable companies considering that channels also catering to such groups or including films pitched to such viewers had commercial value, certain types of films found new venues.

The up side was the fact that films once hard to see or find came into view in a readily accessible manner and allowed many once virtually barred from those films a chance to explore and experience a different kind of cinema. The down side, however, was chilling. Within a few years, many art houses and repertory cinemas and film clubs were extinct.

Once many viewers who loved the foreign (and vintage) film experience were able to view at home, that is exactly what the many did. Somehow, the special magic that comes with seeing films in a theater as a communal experience was gone and film making in general, let alone the European cinema, would never be the same again.

Also, this shift also allowed access to films from other parts of the world and the cinemas of the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Australia began to have their days in the cinematic sun. Europe may no longer have been the hub of the art house world but it still had much to offer as the following list hopes to point out.

1. The Last Metro (1980)

It’s heartbreaking to think that the 1980s would mark the end of France’s Francois Truffaut, one of the greatest lovers of the movies ever, in addition to being one of the foremost practitioners of cinematic art in the medium’s history. The brain tumor which would end his career and life didn’t allow him much time in what was his fourth decade working in the film industry.

However, the output he did achieve during the 80s promised that it would have been another memorable time span for him (he announced that he wished to retire after making 30 films and fell five short of that goal, but he might well have changed his mind about retirement before all was said and done).

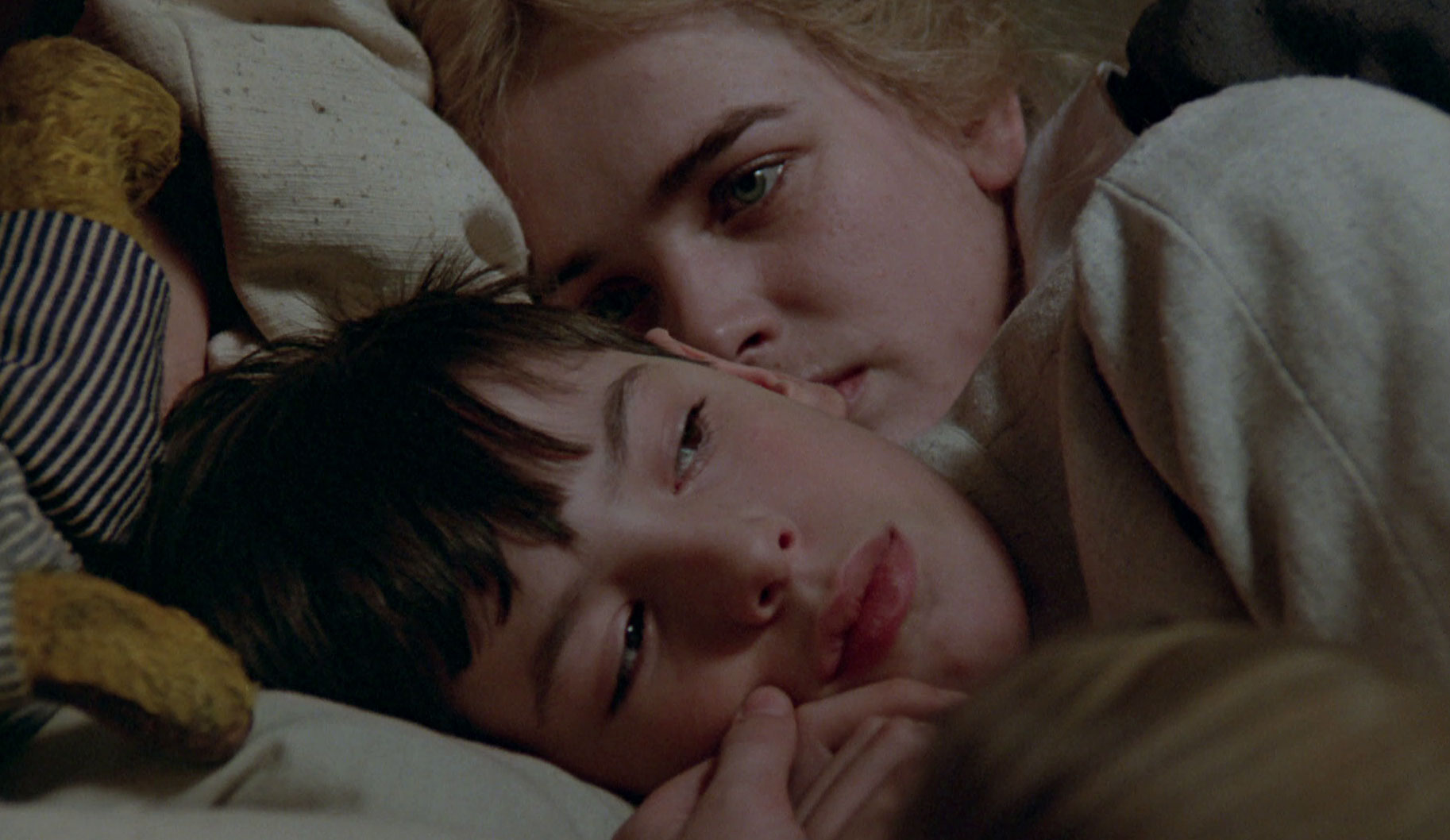

His last big hit was his third from last feature, a World War II era drama entitled The Last Metro. Truffaut had grown up during the war years in occupied Paris and he well remembered those times. The film concentrates on a Paris theater and those who work within its walls.

This is literally the case for Lucas Steiner (the great French actor Gerard Depardieu, in his only Truffaut film), the theater’s manager and director and who is in hiding in the theater’s cellar since he is Jewish. His wife Marion (Catherine Deneuve), who is gentile and not in immediate danger, has long been the theater’s star and also takes over her husband’s job as a way of keeping an eye on things in the theater in order to assure his safety.

During this time they and the theater must also concern themselves with the presence of the occupiers, who wish to censor, ban and berate. The crowd is likewise a concern since many come to the theater in order to keep warm (there was no coal for civilians in wintertime Paris during the war) and must be home before curfew, meaning they must catch the last metro train or be at risk.

The director could always make magic with stories touching on his own life and this one was no exception. Maybe, deep down, he knew time was running out for he poured himself into this film and his collaborators responded in kind (and Depardieu had been quite resistant to appearing, not liking Truffaut’s New Wave work methods in general).

The results swept the Cesars (France’s Oscars) and netted the director his own final Oscar nomination in addition to being a big box office hit in all the countries in which it played. There would actually be two more Truffaut films but this was his true farewell.

2. Lola (1981)

Around the time of Truffaut’s battle with life and death, a prominent German director would also be coming to the end of his life and career, albeit in a much different manner. Werner Rainer Fassbinder always lived on the edge and made films on the edge. Like Truffaut, he also loved films, especially Hollywood films, but saw them in a different and much more astringent light than the gentle French director.

Though his massive television production Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980) was intended as his magnum opus (and for some, it is), many more think of the three films which comprise his BRD trilogy as his masterworks.

The first part, 1979’s The Marriage of Maria Braun, was his theatrical high water mark in many ways (and his only brush with the Academy) but the next part, Lola, not unduly noticed at the time, looks better and better with the passing years. Many have commented that the film bears a marked resemblance to the great German early talkie classic The Blue Angel (1929).

Surely the fact that the indifferent and carnal femme fatale of that film, who destroys a respectable, if pompous, teacher with what passes for her love, is also named Lola can’t be a coincidence. In this film, a post war German city is making its way back to something like prosperity but all the town officials are as crooked as the day is long.

A new commissioner, Von Bohm (the noted Armin Mueller-Stahl) has come to manage and he is quite honest, much to the disgust of Schuckert (Mario Adrof), one of the old guard. Also figuring into the equation is Lola (Barbara Sukowa, Fassbinder’s exceptional go to girl if Hanna Schygulla was unavailable).

Lola has been involved with Schuckert to point of having a child with him but that’s not that big a point as Lola’s life as a cabaret singer (so to speak) has been far from virtuous. She and Von Bohn drift into a relationship which Schuckert will use to his own ends.

Anyone expecting this film to go in the direction of Hollywood political films such as Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington will be in for a very rude awakening, one so typical of Fassbinder. As is often the case with the director, the actors are superb and Fassbinder and his crew conjures up a wonderfully expressive “plastic” style with fits not only the 50s period of the film’s setting but is yet another homage to the director’s idol, German born Hollywood director Douglas Sirk.

Though Sirk was often forced to employ happy endings, he always put an ironic spin on them and here Fassbinder does the same thing (only with much more bitter irony). The director would only have one more year before his substance fueled death but, also typical of him, he’d turn out two more films and start on a third.

3. Man of Iron (1981)

Thankfully, Poland’s renowned Andrej Wadja wasn’t going anywhere but to the set to make another fine film in the 80s. In the 70s he had created one of his finest pictures, the political labor drama Man of Iron (1976), in which a film making student (Krystyna Janda) is censored when she tries to discover what had become of a worker who had been used in propaganda materials to illustrate what the ideal Polish worker should be.

She met the man’s son and discovered the man himself was dead, but why he died remained a mystery (since Communist officials said no to the script’s stated cause, violence during an intense strike that pitted union workers against government troops).

Due to the government restrictions on his story, and the success of the film nonetheless, Wadja decided to create a sequel during a lull in government ordered censorship, during which he was able to make a much more pointed follow-up film.

The result was Man of Iron, which tells the story of the original worker’s son (Jerzy Radziwilowicz, who played the father in the first film, plays the son here). Like the father, the son is a good worker and labor leader who likewise will not lay down for the forces of oppression. He is also now married to the film making student from the first film.

As the film unfolds, the young man is determined to stand firm though the party has sent a journalist to slander him in hopes of neutralizing his influence. There is much here concerning the intense political situation going on in Poland just before the Iron Curtin ended up falling there (and future Polish president Lech Walesa, who is the basis for the title character, appears as himself in the film).

Wadja handles it all with his customary deftness and intelligent dedication. Perhaps the events of the film are now history but the level of artistry remains to cause this film to end up as one of the great dramas of the political cinema.

4. Mephisto (1981)

Hungary’s Istvan Szabo had been a well known director in Europe since the 1960s and his 1966 Father had been Oscar nominated (and Lovefilm two years later was a critical success) but when he switched to international productions in the 80s he finally found a larger success and fame.

A large factor in his good fortunes was a trilogy of films concerning pre-World War II era German figures, each starring the commanding German actor Klaus Maria Brandauer (remembered for his Oscar nominated performance in 1984’s Out of Africa, made during his too short Hollywood stay).

The first and most famous is the Academy Award winning (foreign film) Mephisto. The film is based on a novel by noted German author Klaus Mann, which he based on his brother-in-law, stage star Gustav Gundgrens (who can be spotted as the imposing head of the criminal organization in the 1931 classic M).

Gundgrens was not overtly political himself but had no qualms about playing up to the incoming powers-that-be, sadly the Nazis in this case, in order to get ahead. Though fictionalized, the story rings all too true as Brandauer’s character wills himself not to see anything which might get in the way of his upward movement. His goal is to play his dream role, Mephisto, who induces Dr. Faustus to sell his soul for all sorts of dubious gain.

Yes, this is non-subtle irony, but the real person did indeed have his finest theatrical hour as Mephisto as well. Szabo directed with power and telling irony and he was aided by his main actor’s superb performance. The two would also have success with Colonel Redl (1985) and Hanussen (1988), before trying their luck in Hollywood, both with rather limited results.

5. Fanny and Alexander (1982)

The cinematic world of 1981 was in an uproar over the announcement that one of the cinema’s royals, the legendary Ingmar Bergman, would retire after his next film, a period family drama entitled Fanny and Alexander. (The concerned need not have worried since he kept his hand in directing for television and the theater as well as writing for films virtually up until his death in 2007.)

The resulting film was one of his longest (some three hours in the theaters but over five in the fuller version he later released to TV and home video) and richest films and also one of his more conventional. The setting is a prosperous Swedish town in the early Twentieth Century, which is home to the Eckdahls, a large and loving family who have been respected and beloved members of the country’s theatrical community for generations.

The latest additions to the family are adolescent Alexander (Bertil Guv) and his much younger sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin). Pretty much anyone would envy them their lavish and warm lifestyle in the bosom of a loving family but it all changes when their father (Allan Edwall), much older than their mother (Ewa Froling), has a stroke and dies.

This is bad enough but mom, prettier and sweeter than smart, is taken in by a bishop (Jan Malmsjo) who is a widower and who has lost his own children under odd circumstances. Mom marries the man, whom anyone could have told her was a horror waiting to happen and things get wildly tough for the kids. Thankfully, grandma (Gunn Wallgren)and her loving Jewish companion (Bergman staple Erland Josephson) have a trick or two up their own sleeves.

This film could not be more sumptuous and satisfying. Does the plot sound like something out of Dickens (especially David Cooperfield)? Yes, but the world has loved Dickens for over a century. Yes, the strain of melodrama which many found in Bergman’s work over the years is quite present, and harnessed to his inherent theatricality but it all works in telling a most precisely delineated story which plays out like a tapestry of a another time, place, and style.

Though there aren’t the incisive performances which mark so many Bergman films, the cast, many drawn from the director’s work in the theater and film over the years, give expert accounts of themselves.

Truthfully, the use many European film makers would soon take advantage of with the longer form methods possible in television were foreshadowed with Bergman’s ultimate TV version of the story, which many felt was a superior piece of storytelling, rounding out a great career.

6. Heimat (1984)

Another proof that television began to show the signs of growth which demanded that it be taken seriously in an artistic sense was German director Edgar Reitz’ fifteen hour plus film, Heimat, shown in Germany as a TV miniseries and theatrically in other parts of the world.

Though there would be two other companion series/films (the second longest of all at twenty plus hours), the original is still the gold standard for the series. Heimat in German loosely corresponds to “homeland” and also refers to a type of film which celebrated the German land and its people in the years leading up to and during the Second World War.

In this film, which is set in the little mountain village of Schabbach, a young man decides to leave the woman he loves and go out to see the world in 1919, just after the First World War. Instead of following him on his adventures, the film will stay in the village and follow the young woman’s progress as she ends up the matriarch of a large family by the story’s end in 1982.

Actually, the woman and her family are but a vehicle for exploring the change in German society during those years, as the episodes are set years apart and each one centers on a significant change in the fabric of German life (the other two series push the timeline out to 2002).

Reitz, who has made this series his magnum opus by , uses a variety of techniques, especially switching from black and white to color at key moments, in order to tell a compelling tale which examines a country and its ways and mores more than stating a plot. Heimat was a difficult journey for some and perhaps only a German can fully appreciate it, but it remains a breathtaking cinematic experience.