14. The Story of Women (1988)

Claude Chabrol has often been cited as the “Hitchcock of France” but he often would explore deeper emotional currents than his British/US counterpart frequently wished to plumb. One of his more notable films to investigate the nature of crime and punishment without resorting to becoming a mystery/suspense genre film is this fact based picture taken from events which took place in the occupied France of World War II.

A woman named Marie-Louise Girard became the last women in France to die on the guillotine. Her crime? She was found guilty of having performed 27 abortions, some of them fatal. Ironically, the occupying Germans, who had no problem with mass exterminations of those living outside the womb, had a great problem with the deaths of those inside of it.

In 2004 British director Mike Leigh created Vera Drake, another fact based film about a woman committing abortions. However, his drama, set a bit later in time, presented a basically kind woman trying misguidedly to help other women.

That is not the case in this film as Girard is shown as a selfish and vain opportunist who stumbles into what she considers a good racket by helping a neighbor. Her husband is a POW and she is having a hard time making ends meet so she decides to go into business, though her lack of training makes using her services quite dangerous (as one ill fated couple discovers).

Isabelle Huppert, one of the national treasures of modern French cinema, gives one of her finest performances, a winner of several awards. Chabrol also turns in a quite forceful job.

One remarkable thing about the film is that it notes the hypocrisy of those to put the woman to death but it never tries to make her likeable, much less beatifying her. Such even handedness is remarkable and would be virtually unheard of in places more concerned with political correctness.

15. Round Midnight (1986)

Many have the perception that citizens of foreign countries dislike the people of the U.S and that the French seem to convey this more than most. A paradox in this is the fact that the French also seem to love American culture, the more down-home, grass roots level of the culture, that is.

Many Frenchmen express their love for the world of American jazz and the acclaimed French director Bertrand Travernier (well known for Coup de Torchon, 1981 and Life and Nothing But, 1989) put his money where his mouth was, metaphorically speaking. He found a thinly veiled autobiographical novel about a young French fan virtually stumbling upon a rather fallen American jazz great living somewhat in squalor in Paris due to lots of substance issues and helping the music man find something like redemption in the twilight of his life.

The director also co-scripted the film and went looking for not an actor to play the lead but the genuine article. He located a real jazz great, saxophonist Dexter Gordon, who had also seen some better days, though he wasn’t in the dramatic position of his character. (The director also had to put up a good, strong fight with the producers to be allowed to hire Gordon.)Yes, this is yet another father-son type film (surrogate, this time) but, yet again, it comes off.

Travernier displays a lot of real feeling for the subject and Gordon is the real deal and, unlike many real deals on film, he was able to convey the essence of his music and his persona and ended up with his last great moment in the sun (he won a Grammy for the soundtrack and an Oscar nomination for the performance).

Once again, a director finds honest sentiment by refusing to go for it in a routine or maudlin way. All of this is augmented by the soundtrack of Herbie Hancock, a modern jazz great, who did win an Oscar and also features fine supporting work from Francois Cluzier as the loyal fan and American actress-singer Lonette McKee as a star singer who remembers her old mentor and comes to brighten his life with a visit. Altogether, aurally and visually, this is a splendid film.

16. Monsieur Hire (1989)

Mystery author Georges Simenon is to France what Agatha Christie is to the British mystery and Earl Stanley Gardner is the US mystery scene: competent craftsmen whose large following is partly based on the fact that they were so highly prolific. Simenon is mainly remembered for his novels featuring his reoccurring character, Inspector Maigret.

Those works (and he wrote some 500!) have seen service on screen, often on TV in various countries, but his finest moment in the cinematic sun was achieved by a novel which did not focus on the character, Les Fiançailles de M. Hire. This novel was first filmed as the excellent 1947 French noir Panique (directed by Julien Duvivier) but came off even better the second time when director Patrice Leconte filmed it again (and it was another version of the book, not a remake).

The title character (Michel Blanc) is a tailor working and living in a not fashionable section of Paris. He is a very odd man and not the least bit friendly or likeable but that’s no crime. Or is it? A young woman has been murdered in the neighborhood and everyone is being looked at.

Hire is looking at another young woman himself, his lovely across the court neighbor (the indispensible Sandrine Bonnaire) whom he is peering at from his window. She is hooked up with a loutish boyfriend (Luc Thullier) who did have something to do with the murder and he gets the idea that Hire is the perfect scapegoat for the crime and his infatuation with the woman is the perfect bait.

The film works as character study (and its made clear that Hire is just one of those unfortunate people forever on a different wavelength from others), a suspense film, and a study in mass psychology, as the crowd is all too willing to blame the unusual and unpopular tailor.

Some properties remade in the 70s and 80s were the better for it since their stories needed the freedoms and more complex mores of another age to be told properly. Monsieur Hire is a perfect example of this trend.

17. L’Argent (1983)

Yet another great European career came to an end with this film, but the director was not a young talent cut short. Robert Bresson was and is considered one of the most cerebral, subtle, complex and formal directors in film history and his emotionally minimalist and austere films with deliberately uninflected acting from non-professional actors, which he started making in the 1940s, have long been the staples of critical tomes and film studies. However, his films have to this day been seen by relatively few.

L’Argent, taken from a Tolstoy story which had been previously filmed, was only his thirteenth film (and its odd how many noted film makers manage to created only about a dozen films).

The story follows a counterfeit piece of currency from hand to hand until it comes upon an honest but luckless gas meter reader who will literally lose everything due to this bit of money, though he is innocent of anything to do with creating or passing the bill. Bresson was among the most philosophical and moral of film makers and his point is that wrongdoing concerns far more than those who initially do the wrong and even more than those who are its immediate target.

In the hands of another, this tale, like many of the others stories Bresson films tell, would be melodramatic. Looking at this one that is the last thing the viewer would consider the film to be.

Bresson’s work was, like all great film makers, truly all of a piece and he never lost creative steam up until the very last. L’Argent may not yet be as well known critically as some of his earlier films but it is their equal and a fitting finale for its maker.

18. Fitzcarraldo (1982)

The contentious but fruitful cinematic partnership between actor Klaus Kinski and writer-director Werner Herzog seemed to work in large part due to the fact that Kinski seemed rather insane (especially after publication of his infamous auto-biography) and Herzog seemed serene and self-contained. That is, he seemed that way until the making of Fitzcarraldo, at which time many wondered if he, too, had finally lost his mind.

The film, based on fact, tells of the title character, a would be rubber plantation baron with grand designs to not only build his fortune in a remote part of the Amazon running through Peru but also to build a major opera house there and bring culture to the natives!

A huge part of this madness concerns getting the native workers to haul a massive steamship over steep mountains to the river…the very same thing Herzog had them do for this film (though his film ship was far lighter, thankfully). Kinski and Herzog had been down the Amazon once before (with 1979’s memorable Aguire, the Wrath of God) and had just narrowly avoided killing each other then.

The director wished to sidestep a repeat and originally cast Jason Robards in the lead role, only to have him become deathly ill with a jungle disease and be medically taken off the film, then nearly half completed. Efforts to lure Jack Nicholson failed and Werzog was struck with his perennial leading man. (Singer Mick Jagger had filmed much of a role as Fitzcarraldo’s sidekick but the delay in filming forced him to leave the project and, since the role was written with him in mind, the character was edited from the finished film altogether).

It was insanity made with insanity reflecting insanity but the film has a hallucinatory intensity all its own. Jaw-droppingly, the pair made one more film, Cobra Verde (1989) , but nothing could top this one. Herzog won best director at Cannes (some thought more for endurance than anything else) but shortly thereafter went into making documentaries solely.

Kinski, to no one’s surprise, died a few years after making this film and one of Herzog’s first documentaries was one concerning their relationship, My Best Fiend.

19. Sans Soleil (1983)

Unique is a word too often and lightly thrown around in cinematic circles. There have been many specialized talents throughout film history and many who have taken the less trod path. However, there are not many who are truly unique. Among those few, though, is Chris Marker. Many do not know Marker’s name or his works…or think that they don’t.

Virtually any sci-fi, horror, or experimental film geek, however, knows his legendary short film La Jette (1962), a 30 minute science fiction story made up virtually of still photographs and narration and utterly unforgettable to those who have seen it (and it was remade as Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys).

Marker himself was a true man of mystery. He gave absolutely nothing away about his identity (even his real name during his lifetime), his origins (though he was always considered French) or his thoughts. The most he would say in commenting on his films were that they were just “home movies” and that he couldn’t believe anyone would pay to see them. That’s nonsense, of course, but he was the most personal of film makers. His few feature length films are considered “ films”.

They take on a subject and mainly use existing footage edited together with new images shot by the director and are edited together in a style which can be termed free association. Clearly this is not for everyone. Of his features, the one best remembered is Sans Soleil (“Without Sun” in French).

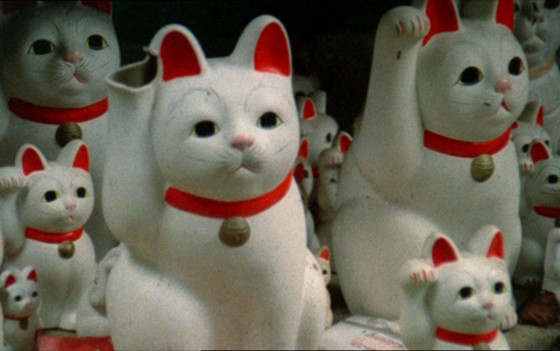

The film concerns itself with the nature of memory and thought with footage showing the differences and similarities of these qualities in humans the world over taken around the world but concentrating on modern and achievement oriented Japan and its opposite number, the primitive Guinea-Bissau, where the natives are happy to just survive and abide with nature.

As with so many others on this list, this is not a film for everyone (no Marker film ever was) but, like La Jette, once seen, never forgotten.

20. The Decalogue (1989)

Yet one more young and promising bright cinematic light snuffed out too soon, Poland’s Krystof Kieslowski achieved a fine body of work in his short life (he died largely due to patriotically refusing to submit to medical treatment anywhere but his somewhat technically challenged homeland).

However, he looked to be reaching his zenith at the time of his death in 1996, having completed his famed “Three Colors” trilogy two years before and was planning a new trilogy at the time of his death (others made the films, showing only how beyond replacement was their originator).

Though several of his early Polish films have come to be recognized in the years since his death (and they are fine films) the one item which was finally brought to international life was the most singular thing in the most unusual format with which the director was ever involved. Even in his lifetime, there were references from those in the cinematic know to a limited series TV production Kieslowski had co-written and directed for Polish television.

The series was entitled The Decalogue and was a modern day interpretation of the Ten Commandments, illustrating how they fit into the lives of modern people who either observe them or not. This sound so didactic and moralistic but it is far from being either, though it is highly moral.

The series has few overt references to religion and none at all to the tumultuous political events within Poland at the time of filming. The stories are all set in the same apartment complex and characters from one story can often be seen in the background of another, though the stories don’t cross.

The qualities which make the series so special are its subtle moral complexity (even in the episode concerning killing) and what was the director’s greatest gift, his uncanny knack for provoking a sense of involvement within the first few minutes of any of his projects. Many became anxious to see this production after it was learned that two of Kiesslowski’s best films, A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love (both 1988) were expanded versions of episodes from the series.

The production was finally shown outside Poland in theaters at its unwieldy length of ten hours before finding a more suitable home on home video. Unfortunately, the company importing the project labeled the episodes with the number of the commandment taken from The Bible when, in fact, they were originally labeled episodes 1 through 10, with the viewer left to decide which commandment or commandments were the topic of the episode.

This has been called the finest television project of all time and it is surely a fine film, even if not originally shown in theaters. Few who have ever seen it have been left unaffected by it.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film,cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.