Released in 1941 Citizen Kane would eventually go on to be known as the ‘greatest film of all time’, it made a star of its director (also lead actor & ‘co-writer’) Orson Welles.

Nominated for Academy Awards in nine categories, one can be forgiven for forgetting it didn’t actually win Best Picture (that went to John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley). One category it did receive award and long-lasting praise for was Best Screenplay, over the years this has been discussed, criticized and even debated over matters of the legality of its authorship.

Over seventy years later, the aim of this list is to try to put the film’s equally noteworthy cinematography to one side and examine what the screenwriter might learn from the Citizen Kane today. (This list does contain spoilers.)

1. Understand the Texture Of A Story

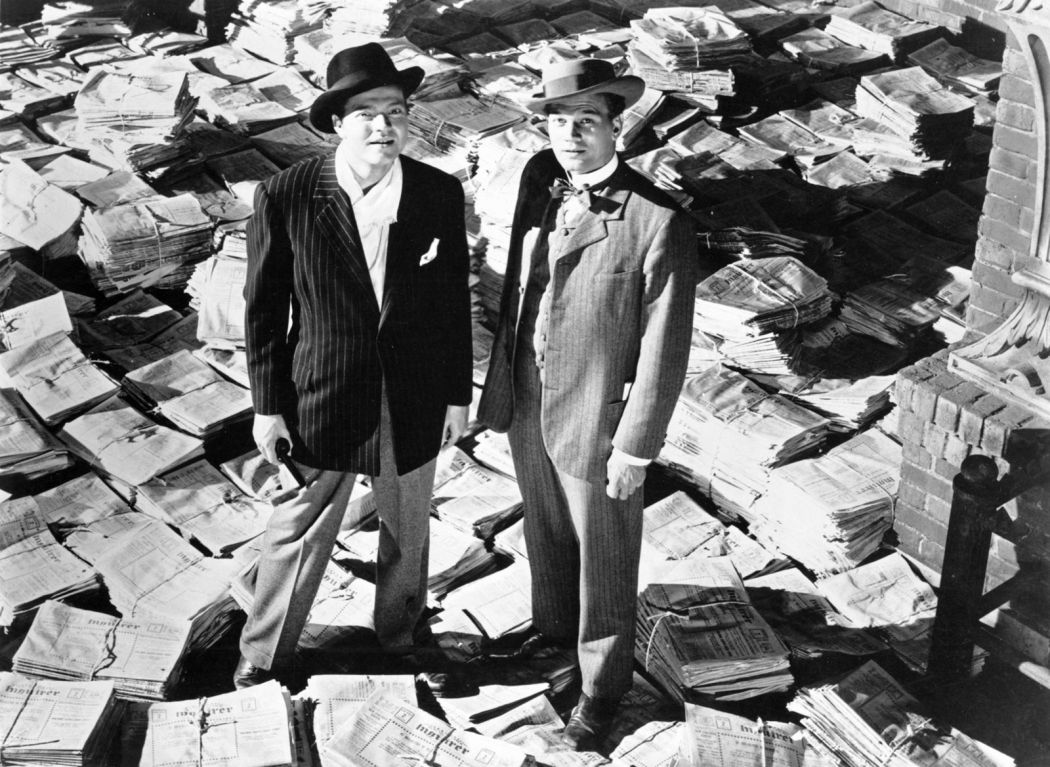

More practical and less stylistic than it may first sound, understanding the texture is all about making use of the arena (‘the world of the story’ – the location, profession, time period) to full potential as part of the fabric of the script. Citizen Kane is set within and against the backdrop of the world of newspapers, news reports and investigative journalism.

Therefore, the narrative’s quest for ‘truth’ or the stories behind the stories amid what equates to a ‘scrapbook’ of interviews relating to the news articles, sound bites and headlines (one might even say ‘cuttings’) we have seen within the film’s opening is well within the context of the arena of the story.

This gives a script added depth, allowing themes to be conveyed with greater potency. In short, it aids credibility and the suspension of disbelieve, the story feels crafted from the arena, from reality (which in this case it was – see lower down). As a comparison, a more recent film which perhaps misplaced the world of its own story was Indiana Jones’ and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Like the previous films within the series this is set within a world of early/mid 20th century archaeology, the investigation of the ancient past. While audiences were ready to accept this may involve ‘fantasy elements’ (all grounded within ancient past/beliefs/faiths/folklore), the extension of this to suddenly include aliens, more conventionally associated with science fiction and futuristic arenas was perhaps what grated most with the viewing public, straining the suspension of their disbelief.

Citizen Kane feels crafted because of its awareness of its arena – one that operates in tune with its story. If Kane had been a prolific actor, the journalistic approach, despite fitting with a world of headlines, would not have carried the same depth.

2. Flaws Are Interesting

Flaws are what make us human; having flawed characters is what makes them more human, more credible, more interesting and aid an audience in emphasising with them.

Credible characters an audience can emphasise with help to maintain their interest. Kane may have been an incredibly wealthy and successful publishing tycoon but it is his flaws, quirks and failings which make his story interesting. His dying words are the ‘flaw’ which keep the story moving (see below).

When do the audience first realise that Kane isn’t as perfect as – arguably not when they are told of his political failings and/or diminishing size of his publishing empire, but rather when he is seen to simply drop/fumbles a trowel of cement in a newsreel. The average audience member may not have experience of the rise and falls of political and publishing notoriety but they have all at one time or another – dropped something by accident.

The fact that this occurs in public, recorded by the press, fuels this empathy further, with the audience, possibly even subconsciously, thinking ‘how embarrassing’. The brief incident allows for an early visual empathic bond between Kane and the audience, it’s a throw-away moment but it is there.

3. Mistake and/or McGuffin?

The greatest film of all time also contains one of cinema’s greatest ‘mistakes’. No-one is actually visibly present in the room to hear Kane mutter his dying words, we see the house-maid rush into the room after the snow-globe strikes the floor. If no-one was actually present, then no-one could repeat the words and create the mystery which drives the story.

According to Welles, this mistake is more to do with the shooting and /or editing of the film than the script. However, the fact that the film still functions perfectly well with this mistake informs the writer that all which was required was a suitable McGuffin (a plot device to give some initial drive/direction to the story) to set the investigative mystery aspect of the scrip into motion.

McGuffins have been covered in similar lists on this site (see the briefcase in Pulp Fiction), once the audience and the characters have to desire to gain enlightenment for what these words mean, they forget the exact question and seek only for ‘an answer’ in this case the words trigger a meandering investigation into the life of Kane.

It is noteworthy that this error occurs within the opening minutes of the film – the first half of a narrative being when an audience are more likely to accept/fail to notice ‘happen-stance’ assisting the plot/characters. Welles’ mistake here offers the perfect example of how an effective McGuffin may be all a script requires to ‘jump-start’ it and propel the narrative onward with subtle economy – the audience follow to script’s peaks and troughs but always stay curious, searching for that answer.

In some ways this could be error could be regarded as complimenting the news theme – would something be newsworthy/arouse our curiosity if we weren’t told it was/should do – perhaps Welles was knowingly using this mistake as a McGuffin to play along deliberately.

4. Visual Tapestry

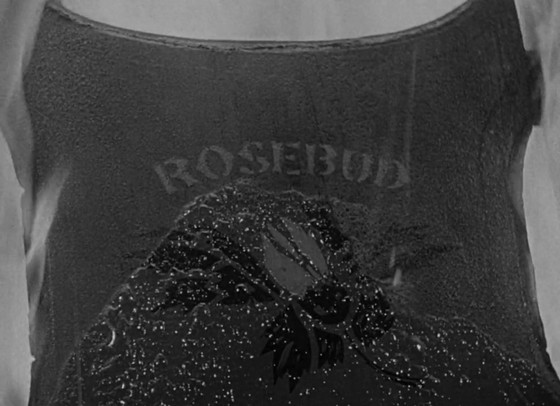

Above all else the screenwriter is repeatedly told to show don’t tell and use the screen as a visual medium. Citizen Kane offers the writer various lessons in this. Consider the snow globe which Kane drops to the floor in his final moments, consider the ‘paper’/’snow storm’ which scatters across the screen. In the centre of this globe is a small house or cottage which is understood to represent Kane’s childhood home – the place where he abandoned his sledge ‘Rosebud’.

The script can be viewed as a journey or quest into the inner psyche of Kane’s mind, with the overarching question – what did his final words mean? The clues to all of this seeming scattered like the paper or snowstorm as the globe shatters like the fragments of his psyche – something both viewer and characters are now trying to piece back together.

The snow globe and its contents becoming an almost surrealist visual motif for Kane’s mind, at the centre of the globe and epicentre of the snow storm alike rests the meaning of his final words.

The screenwriter should search for appropriate and effective visuals to aid the telling of the story. These, will often be open to broad interpretation but a well woven visual tapestry allows for a rich, rewarding and re-watchable narrative experience.

5. Snakes & Ladders

Following on from the above, Citizen Kane is frequently referred to as a ‘puzzle’ or ‘kaleidoscope’. This is all very well for the viewer, enjoying the ride and trying to make sense of the riddle but potentially hazardous for the writer.

Citizen Kane and mystery scripts like it can easily go very wrong, too many stories within stories, layers within layers and in the end the clever enigma the writer hoped to leave audiences with just leave many confused, frustrated and/or underwhelmed. There are plenty of conflicting views regarding the more recent Inception as an example of this.

As Citizen Kane is a story made up of its characters stories in a series of non-linear flashback type segments – some of which could be considered as unreliable (see below), it presents a strong example of how complex a story of this nature could be. One approach could be to consider the script as a large chequered board – each cheque or square a scene or beat within the story.

Now add some snakes and ladders. Instead of steadily advancing one square at a time the story may miss a few squares and go up a ladder with an insight into Kane’s life via an interview or story; or just as equally miss a few more squares as it travels down a snake before advancing again. This leaves a few gaps of uncovered ground/squares and ‘retreads’ recovering old ground yet slowly but surely each square reveals part of the story.

The gaps are those unexplained areas open for speculation, the retreads are those ambiguous areas open for interpretation – was the information reliable/truthful or not. One might imagine working this structure using post-it notes – possibly shuffling a reshuffling the order – even removing elements.