6. Be Biographical – If You Dare!

Of course, legalities apply if the writer is going to develop a serious biographical work. However, Citizen Kane offers an example of the pros and cons of taking a story from the everyday headlines and turning it into a feature-length screenplay. It is no secret that many widely interpreted the film’s central character to be based upon the publishing giant William Randolph Hearst (extending to several of his ‘rivals’).

Although Welles never rigidly confirmed this, it seems clear he was making use of the world around him, taking inspiration from a character and story which already existed.

Welles had his own ready-made story, the plus side of this – (if working on the principal that in truth an audience/consumer actually favours a high percentage of that which is familiar to them) an audience would already recognise this and hopefully flock to a reflection or interpretation of the world around them.

The negative in Welles case was that Hearst took exception to the finished film, seemingly finding most offence in the apparent parallels between the character of Susan Alexander Kane and Marion Davis an actress with whom he was romantically involved. Hearst then refused to have any mention of the film in any of his papers, something which could surely only hinder the box-office success of a young director’s debut feature. After all, something is can only be a public controversy if the public know about it.

The lesson here is that making use of high-profile stories and public figures and ‘fictionalising’ them can save the writer some leg-work, whilst also possibly making a script more commercial by being topical. However, legalities aside, as Oscar Wilde said ‘the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about’ , in Citizen Kane’s case it teaches the writer to think twice before scripting something which will fall foul of ‘higher authorities’.

7. Fuel Characters With Some Of Your Own Idiosyncrasies

This should not be taken to imply that just because the writer has a hobby which interests them greatly it should become an irrelevant detail of a character’s back-story. Nor does it mean that a script should be littered with references to an obscure band the writer favours. The driving mystery as to what Kane’s dying word(s), ‘Rosebud’, mean or refer to within the script is equally as bigger enigma outside the script.

Despite urban myths that it was Heart’s pet-name for part of actress Marion Davis anatomy, co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz offered a different and more practical explanation relating to his own childhood. As boy Mankiewicz was visiting a public library, leaving his bicycle unattended outside, when he returned the bicycle had been stolen.

The Mankiewicz family would seem to have viewed this as carelessness and refused to pay for a replacement as punishment. Presumably this hurt and frustrated Mankiewicz greatly, but the story continues that as a young man, he bet on a horse in the 1914 Kentucky Derby named ‘Old Rosebud’ – the resulting winning enabled him to ‘buy independence’ from his family. All of this apparently came to light during therapy sessions in which he would mutter ‘rosebud’.

The conclusion was that the bicycle incident and the horse had somehow become intertwined within his own mind, symbolising both a lost freedom of childhood and desire to gain the power to be able to buy it back. As an audience we might draw similar conclusions as to why Kane mutters these words; words so cryptic, ambiguous and ‘random’ that they could only have been plucked from reality – or the writer’s own restless mind.

8. Seeing Does Not Always Have To Be Believing

There is a common ‘rule’ within screenwriting that if the audience see something, it must be true (the sharing of a secret), if one character merely speaks information to another character, then this could be false.

As an example, consider the typical ‘detective gathers the suspects’ sequence at the close of a murder mystery, this usually results in a visual flashback to confirm for the viewer what did actually happen. However, such ‘rules’ are often there to be ‘disregarded’ and Citizen Kane offers example of this with its lengthy sequences offering information from different possibly unreliable narrators.

In the case of Citizen Kane, in the context of a scattered search (see above) for truth/an explanation amid fractured aging memories this works well to compliment the story – adding more depth and carefully opening up more questions than it answers, allowing the audience to fill in the blanks.

In some contrast to this, whilst also working along the theme of memory, the aging mind and perhaps a lost ideal, one of the film’s memorable quotes is the anecdote concerning the young woman in the white dress with the parasol, someone who Mr Bernstein assures he hasn’t had a month of his life go by without thinking of.

The tale is resonant but would lose all impact if the film had suddenly launched into a flashback depicting this. Perhaps such a memory strikes a cord with the viewer, we don’t see but we believe. Citizen Kane therefore offers a example of the writer perhaps better flouting rules and using their own good judgement.

9. Writing Partnerships Can Turn Complicated

It is no secret Citizen Kane wasn’t without its complications. Following Welles’ notorious 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast he was hot property and was signed to R.K.O with an unheard of contract that he would write, direct and star in two pictures as long as the projects had the studio’s approval. Furthermore, Well’s was also granted the last word/approval on the final edit of the film. His first project was to be Heart of Darkness (based on Joseph Conrad’s novel – later forming a basis for Apocalypse Now).

For his second project, Citizen Kane, Welles devised the concept with Mankiewicz who would go on to write the first draft of the script. In time Welles and ‘Mank’ (as he referred to him) would make agreements on story and character before going on to write separate drafts. It was apparently Welles who then went on to fuse and edit these separate drafts into the finished script.

Controversy arose when Welles was accused of downplaying Mank’s role in the screenwriting process. Attention was directed toward a stipulation in Welles’ contract that Welles be recognised as ‘author and creator’ of the work, with Mank regarded as a ‘script doctor’ and signing his own contract as such.

Upon release Mank did receive a credit as writer on the finished film but Pauline Kael resurrected the debate as to the ‘true author’ in 1971 before Robert Carringer’s 1978 study of R.K.O script records proved Welles to be the definitive author of the finished work. The story here could almost become a script in itself but the lesson for any writer is to be wary of what you agree to and who you work with, success can out a different light on proceedings.

10. It’s About Enjoying The Journey Not Just Reaching The Destination

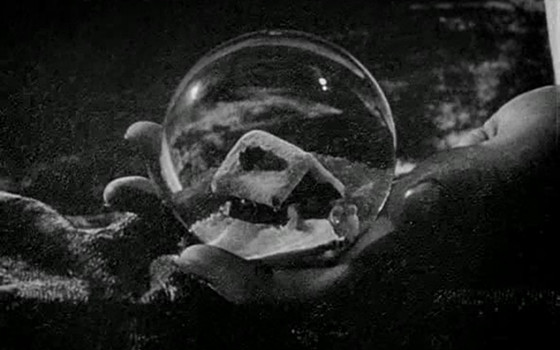

Plot spoiler –Kane’s dying words refer to a sledge he owned as a boy, a secret made clear to the viewer but not the characters in the closing scenes of the film. But wait, does it really matter if the viewer already knows this – would this prevent them from watching the film repeated times? Probably not. The answer the viewer has been seeking is given – albeit to the question ‘what’ does Rosebud refer to, this leaves the viewer to speculate, re-watch to consider ‘why’ this is so important to Kane.

Knowing what his final words refer to, although central to driving the plot, does not diminish the viewing experience, the secrets the viewer shares with Kane and the other characters along the way offer a journey littered with clues and differing interpretations. The writer needs to remember this, make the peaks and troughs, the twists and turns of a narrative compelling and the result is a rewarding screen experience – get this right and the audience will revisit and re-watch again and again.

In the case of Citizen Kane, the audience enjoy being immersed within the puzzle, the investigative journey – something the cinematography also allows for. Did anyone stop watching the Empire Strikes Back because they knew that Darth Vader was Luke Skywalker’s farther – no. Does the fact that we all know Bruce Willis is a ghost in The Sixth Sense diminish viewing pleasure? The jury is out.

Author Bio: George Cromack is a tutor at the University of Hull and also Coventry University’s Scarborough Campuses; with a BA in Scriptwriting he also teaches evening classes in Creative Writing, Scriptwriting and Film Studies for the WEA. Working towards his PhD focusing on Folk Horror, he is a keen writer of both prose and script, Cold Calling, a film short written by George premiered in October 2013. Follow him on Twitter @MadBasil.