11. He Who Gets Slapped

The circus is the setting for this multi-layered MGM melodrama with an all-star cast including Lon Chaney, Norma Shearer and John Gilbert.

In one of his best roles, the incomparable Chaney plays a scientist who was once betrayed by the ones close to him and ended up a bitter clown in a humiliating act. He loves the young Consuelo (Shear) in silent and does everything to protect her from the same people who ruined his life.

Chaney transits easily from outbursts of sadistic violence to heartbreakingly pitiful moments. He gains the viewers sympathy and holds it even when taking morally ambiguous actions, because we know his turn for the worse was not really his fault. By the end of the film, it becomes clear that the circus theme is not so far-fetched, but really a simple metaphor for a society that instead of helping sufferers, finds amusement in their pain.

12. Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages

After the commercial success of his controversial film The Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith was certain his narrative and visual innovations had been accepted by the public; however, the accusations of racism he endured were abundant and heavy. After weighting in the good and bad feedback of his first epic, the master filmmaker embarked on the making of another, and he made sure to use it as a come-back to his critics.

Intolerance, like its predecessor, is over 3 hours long. Griffith’s public had proved it could assimilate more complex, long storytelling and he took it to the next level by telling four parallel stories about intolerance through the ages ( a contemporary drama, a Judean segment, a French storyline and the famed Babylonian empire part). The sections are connected by shots of an ethereal Lillian Gish as the Eternal Mother rocking her baby.

With its lavish sets, hundreds of extras and intense acting, Intolerance is irrevocably one of the Silent Film era’s great works of art.

13. It

The film that gave legendary actress Clara Bow her nickname – the It girl – is an unpretentious and perfectly entertaining romantic comedy, in which she plays a salesgirl in love with her dapper boss.

The Clarence Badger production has been elevated to classic status by the magnetic screen-presence of Bow, who, without a doubt, had lots of “it” no matter the definition applied.

The iconic actress is charming and full of life, and Spanish performer Antonio Moreno more than manages to keep up with her seemingly boundless energy.

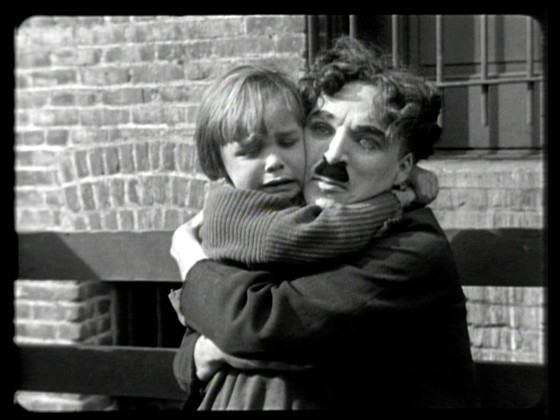

14. The Kid

“A comedy with a smile – and perhaps a tear”, as the opening title announces The Kid is a carefully balanced masterpiece, in which Charlie Chaplin delivers a sentimental story with quite a few hilarious moments to even things out perfectly.

The plot has the celebrated Tramp character finding and caring for an abandoned boy as if he was his own, when circumstances unexpectedly threaten the relationship. Chaplin and Jackie Coogan make a remarkable duo on the screen and even leading-lady, Edna Purviance, takes a back seat to their charming interplay.

The story moves at a fast pace with enchanting simplicity, Chaplin is at his best funny/poetic self and child-actor, Coogan, is just as remarkable and memorable. For that and much more, The Kid has justly earned its position among the best silent comedies ever produced.

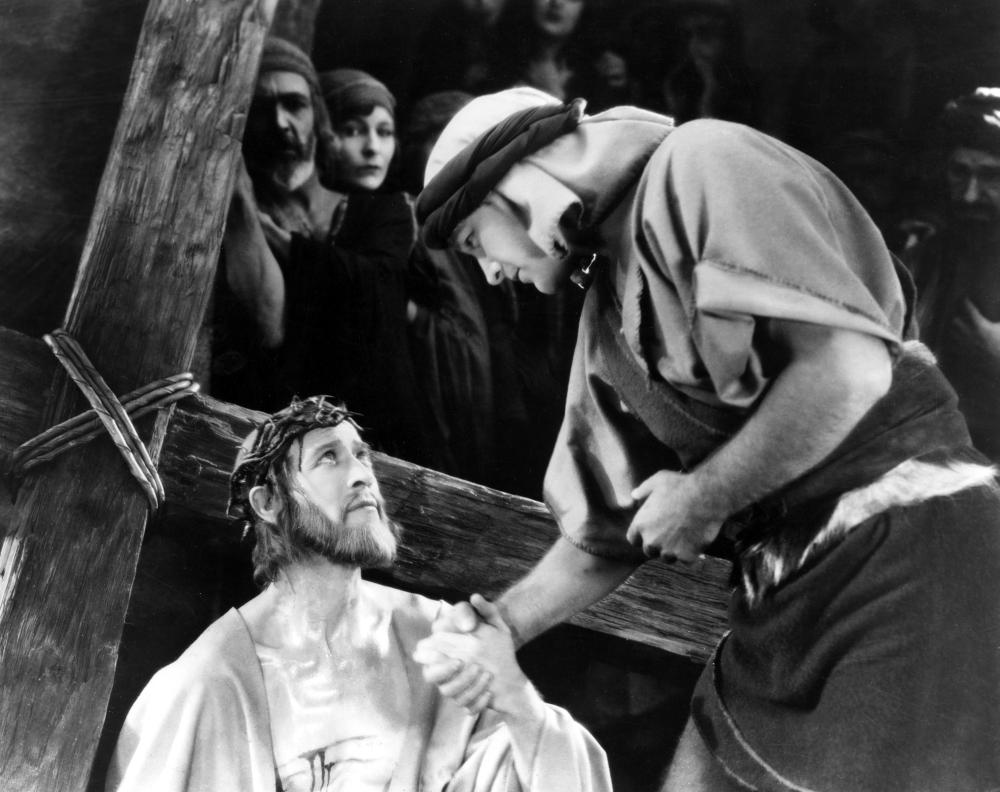

15. The King of Kings

The life of Christ was one of the first subjects Movies took an interest in telling, but arguably no director, before or since 1927’s The King of Kings, told the well-known story in such a respectful and touching way as Cecil B. DeMille.

DeMille’s flavor for high-value productions and spectacle movies is legendary and when the theme in question calls for them, there’s no stopping him. Hundreds of extras, immense sets and some top-notch lightening techniques that have Jesus literally glowing are just some of the film’s main attractions.

Christ’s crucifixion, done in a dignified and reverent way, is probably the best moment in the movie, but be sure to pay attention to the Resurrection sequence, beautifully shot in two-reel Technicolor.

16. The Last Command

The film that won Emmil Jannings his Academy Award as Best Actor would make any list of the best self-related Hollywood films. The German actor plays a former Russian general, who ironically ends up an extra, in a film about a tsarist Russia military authority.

Expert director Josef von Sternberg treats us to a story told in flashbacks, from Jannings glory days as a the czar’s right-hand man to his ultimate humiliation in Tinseltown. William Powell, in the early-stage of his career, has the role of the Hollywood director and delivers an efficient performance, but the spotlight never leaves Jannings, who mastered the art of playing suffering characters.

Evidently drawing a parallel between the extras’ maltreatment and the that of the impoverished Russians, von Sternberg constructs an impeccably structured story that builds up to a most impactful climax.

17. Lonesome

The idea behind Paul Fejos’ underrated masterpiece is simple enough, in fact, it’s almost a cliché: two lonely people, in a crowded big city, find each other and fall in love, only to be separated and forced to go back to their lifeless routine.

Fejos uses some extremely sophisticated visuals to express the loneliness of the main characters, and sets a frantic pace to go along the agitation of the city. The editing is a work of craft, especially the memorable sequence of the couple going about their day in parallels.

The film had the misfortune of being released when sound had just been introduced, so it does suffer from three sequences with a static camera and some flat dialogue, but even these interruptions can’t take the magic away.

18. Modern Times

In his farewell to the screen, the Tramp finds himself struggling to live in industrial society. From its first shot, comparing a flock of sheep to the workers of a factory, Modern Times offers social commentary disguised in classic Chaplin gags.

Released years after Silent Cinema had been professed as dead; the film also reflects Chaplin’s distrust about the very technology that enabled Sound Pictures: Although it does carry sound-effects, they are used to enhance the soulless future of Film the director feared would soon arrive.

Another highlight of the movie is the beautiful Paulette Goddard, the only one of Chaplin’s wives who would go to have a successful career of her own. She plays his love interest, the gamine, who, at the end, famously goes off with the Tramp to the haunting song ‘Smile’.

19. The Phantom of the Opera

Universal’s version of the Gaston Leroux novel has Lon Chaney in his most memorable role. As the original screen Phantom, the “man of a thousand faces” delivers such an imposing performance, no actor who ever reprised the role came close to duplicating the sheer impact of his legendary portrayal.

The sets are elaborate and remarkably detailed, but the art-department highlight goes to Chaney’s horrifying make-up. The scene in which he reveals his true face to Christine is quite distressing, even to modern-day audiences.

The two-strip Technicolor ball scene is also famous and not without reason. But technology is not what makes the film a classic, if that was the case, at least one of the countless subsequent versions would have surpassed it in quality; nevertheless, it remains the definitive screen account of the tale.

20. Queen Kelly

Queen Kelly was originally planned as a five hour epic, but due to financing troubles and leading-lady Gloria Swanson’s dissatisfaction with the direction the plot was taking, only the first act was shot to completion.

In its 101 minutes of fascinating available material, we see a convent girl being abducted and then moving to East Africa to live with her aunt, who runs a brothel.

The remaining Queen Kelly is a bizarre tale that deals with hypocrisy and sexual repression. A small part of a much longer and comprehensive story that Stroheim aimed to tell. However, it is more than enough to serve as a testament to his skill; and as prove, that even Hollywood at times does not know how to make the most of its stock of talent.