The Romantic Western figure is a staple of American folklore and has extended its reach in poetry, music, literature, and most especially film. Tales of cold-hearted bandits and moral law enforcers, corrupt sheriffs and mistaken outlaws set against the backdrop of the undeveloped and expansive Old West that held promises of fortune and enterprise.

In 1903, Edwin S. Porter made the iconic film The Great Train Robbery, a short work that tells a start-to-finish story of a group of outlaws who rob a train, kill a few people, and then get hunted down and killed themselves. This formula became the run-of-the-mill representation of the Western, the apparent lawlessness made even more blatant in the film’s final shot of actor Justus D. Barnes firing his revolver at the camera/audience.

Once films became longer and more linear, the Western was romanticized. The advent of sound allowed romantic subplots and emphasis on the hero. Hollywood’s Golden Age produced Western icons in John Wayne, Montgomery Clift, and Gary Cooper.

Directors like John Ford and Howard Hawks made films that became instant classics, romanticizing the lone gunman fighting bandits, and Indians (although the latter subject foreshadows the eventual demythologization of the Myth of the Old West) in picturesque locales like Monument Valley. Themes of Westward expansion and manifest destiny was the most common theme where man’s definition is owning land and upholding justice.

Although such common themes worked for the Western throughout Hollywood’s Golden Age, John Wayne’s rough-and-tumble yet youthful image from 1939’s Stagecoach got a grittier makeover in 1956 with The Searchers. Widely regarded as the greatest Western ever made, the film portrays the aging star as a bigoted and violent man. Still an image of the Old West, Wayne’s character Ethan Edwards is framed by a doorway by the film’s end and walks off alone into the massive horizon alone.

This iconic image signalled a change in the Western mythos. Since The Searchers, many filmmakers began to disassemble the characteristic traits of one of cinema’s most popular genres, and while John Ford and and other popular directors continued to crank out formulaic Westerns, the genre was on the wane.

In the decades to come, New Hollywood Cinema and the rising influence of World Cinema began to signify a change in what was already familiar. Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch gave audiences a bloody and bullet-riddled requiem to the Western hero while a new movement was found in Europe in the 1960s: the Spaghetti Western.

In the 1980s, novels like Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove presented ultra-violent and tragic views of the Old West retaining the genre’s epic nature but telling a wholly different story. The aging image of John Wayne gave way to the likes of gruffer and morally ambiguous character actors such as Clint Eastwood and Warren Oates. The Western would never look the same again.

For this list, a selection of films that both aided in the debunking of the Western myth or are direct effects of said changes. They retain some of the Westerns formulaic traits, yet completely flip them on their heads, challenging societal understandings of a Romantic era, commenting on the violent history of America, and even changing the perceptions of certain Western stars by the stars themselves.

1. High Noon (1952) – Fred Zinnemann

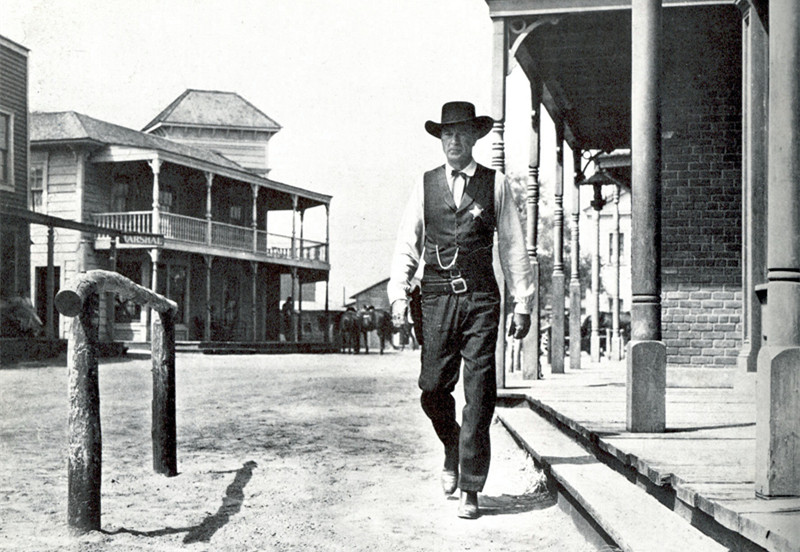

The earliest addition to the list is formulaic enough in its pacing and story. A band of outlaws long to gun local sheriff Will Kane down out of vengeance. Shirking all his sheriff responsibilities in order to settle down with his recently married wife, Kane turns to the townsfolk to help him stand up against the oncoming threat… only to find out that they are all refusing to help him. Now standing alone, Kane must face being outgunned and outnumbered on both sides of the law.

Despite the standard story, the subtext of High Noon gives the film its layering. Open to multiple interpretations, High Noon’s main point of controversy was its subjective treatment of the Red Scare which was happening at the time.

Communism was a threat to America’s moral fiber and the film’s screenwriter, Carl Foreman, was a blacklisted former Communist who refused to name names when called upon by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Blacklisted for not caving under pressure, ostracized by fellow Hollywood types who turned tail and did name names to HUAC, Foreman channeled his frustrations and embodied them in the moral, yet abandoned character of Will Kane.

Still being a hit with a happy ending, High Noon was one of those films that helped start the “demise of the Western” trend that was starting to unfold in the 50s. Winning four Oscars, the film does stand out on its own today, even despite the Western’s golden boy, John Wayne, calling High Noon “the most un-American thing I have seen.” Interestingly enough, the film was also attacked in the Soviet Union due to its praising of the individual.

2. Shane (1953) – George Stevens

Another early film that help shuttle the Western to its demythologization and “demise” as many scholars call it, Shane was another individualistic story told from the eyes of an unwanted man with good intentions. Rather than focus on the smalltown politics of High Noon, George Stevens’ Shane is set along the backdrop of the Western frontier, a landscape often explored in classic Westerns.

The titular Shane is a wandering drifter who stumbles onto a land war. Siding with the victims of gangsterism, Shane acts as a lone protector of a family undergoing pressure from a ruthless cattle baron. What follows are a series of debates and violent events that present a critique of America’s big business interests in the formulation of the Western frontier.

Alan Ladd plays Shane, who is of little words and of tough demeanor. Yet at the same time, despite being the film’s protagonist, he is subject to rumors and has a possibly violent past that he is trying to escape from. Taunted by the cattle baron’s gunslingers and soldiers of fortune, Shane’s hand eventually is forced to exact brutal justice, making him no better than his antagonists.

The film’s closing scenes, of a wounded Shane riding off into the sunset towards almost certain death was a new and bleak image of the prototypical invulnerable Western hero. Lauded by critics and hailed as a Western cinema masterpiece, Shane presents an atypical view of a Romantic hero.

3. Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) – Sergio Leone

After the 50s saw Hollywood play around with the notions of the individualistic gunslinger as hero, the Western was on the wane, with many titles being reverted to B-movie status by the time the 60s came around. However, the Spaghetti Western movement taking place in Spain and Italy during that decade presented a grittier and more violent approach to Western cinema.

One such director who enjoyed breaking the rules in terms of genre was Sergio Leone, who already hit it big with his popular “Man with No Name” trilogy, making a young Clint Eastwood a star worldwide. Leone’s masterpiece in genre-breaking came with 1968’s Once Upon a Time in the West, a modern epic detailing Westward Expansion, corporate greed, lifelong vengeance, and roads to redemption.

The film follows four characters, each from different walks of life and social classes. Each one has a vendetta to settle, either against society or with each other, and it is all told through Leone’s zen-like camera angles attributed to Akira Kurosawa’s samurai films. The opening sequence unfolds a violent gunfight that sets itself up through diegetic sound and extreme slow pacing, suddenly exploding in a maelstrom of bullets and death.

A main point of genre-breaking that Leone also gave audiences was in casting all-American good guy Henry Fonda as a ruthless child-killing bounty hunter/enforcer for a greedy land baron. His blue eyes shine bright as he gains a certain gratification from killing.

The film seems amoral at times, with the heroes gunning down outlaws, lawmen, and each other over the course of the film’s nearly three-hour runtime. Despite this, Once Upon a Time in the West is an unrivalled classic. Often mimicked but never topped.

4. El Topo (1970) – Alejandro Jodorowsky

After the phenomenon of the Spaghetti Western, Chilean-born filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky took the Italian formula for the genre, and infused it with experimental surrealist imagery and themes. The bastard creation unique to Jodorowsky’s style became the operatically violent El Topo.

Casting himself as the titular character, Jodorowsky portrays El Topo in a mostly silent manner. Told in two parts, El Topo ventures into the desert, finding apocalyptic atrocities wreaked on villages and innocents. He wanders and doles out justice until he is given the task of defeating four great gunslingers in order to become the greatest gunslinger in the world.

After being tricked by his muse and his female alter ego, El Topo spends the next few years in solitude, eventually re-emerging as a god-like monk who takes on a village full of cultists. His journey runs full-circle as El Topo’s past comes back to haunt him.

El Topo is not a Spaghetti Western in the true sense of the genre, but the genre’s violent content and near-silent dialogues are definite influences on Jodorowsky’s strange film. The filmmaker adds some unique touches to his character, galloping through the desert shaded by an umbrella, a naked child his only other accompaniment.

The film begs many questions, but was worthy enough to become a midnight movie phenomenon at the time of its release, garnering praise from artists and critics alike and has set a template for many experimental Westerns and art films that came after it.

5. McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) – Robert Altman

After Sam Peckinpah blew the Western tradition away with The Wild Bunch in 1969, it was not easy to come by a Western that could dynamically mimic the message Peckinpah was going for with his magnum opus. However, in the era of New Hollywood cinema, filmmaker Robert Altman was crossing lines and breaking boundaries with his own unique brand of cinema.

Already well-known for his breakdown of the war film with his comedy M*A*S*H (1970), Altman set his sights on the Western with an intention to completely upend the genre’s dominant traits. The lone hero, the quaint village, the woman with the heart of gold, the outlandish brute; all of these characters get a makeover in McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

Set at the turn of the 20th century, John McCabe arrives in the town of Presbyterian Church, Washington where he aims to strike it rich and set himself up for a life of relaxation and gambling. Playing on legendary rumors that he is a cold-blooded gunfighter, McCabe becomes a local playboy amid the town’s small mining community.

Teaming up with a British madam named Constance Miller, the two run a brothel which makes the town prosperous. With prosperity comes corporate interest, however, and McCabe and Mrs. Miller become embroiled in a land war with the local mining corporation who would rather settle things violently than negotiate.

This film plays on the notions of the Western hero even more than High Noon, Shane, and The Searchers combined. McCabe is a bumbling man clearly only interested in himself, Miller is an uncouth madam whose Cockney accent distinguishes her as an outsider.

The film’s setting is most definitely in the West, but instead of deserts and plains, Presbyterian Church is in the forests of the Pacific Northwest. The final gun battle is more a game of fearful cat-and-mouse where McCabe only finds advantage through hiding from rather than confronting his enemies. The film plays with the formula brilliantly and along with Vilmos Zsigmond’s grainy photography (in order to give the film an old photographic look), solidified McCabe & Mrs. Miller as an atypical Western.