6. My Name Is Nobody (1973) – Tonino Valerii

The main choice for most comedy-Westerns is almost always Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles (1974). While being a funny film and poking fun at the tropes of Westerns to the point of absurdity, Blazing Saddles is indeed a comedy that is a Western while Tonino Valerii’s My Name Is Nobody is more a Western that is also a comedy. This slight difference is why Valerii’s film appears instead of Brooks’ to chronicle the Western Comedy.

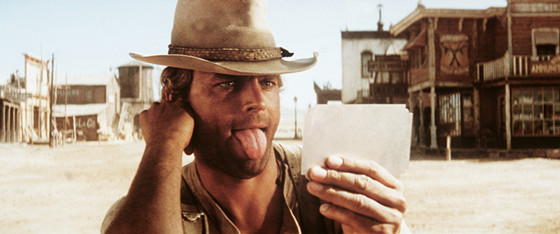

Conceived as the “ultimate joke” on Spaghetti Westerns, My Name Is Nobody contains the token gritty violence akin to the genre interspersed with instances of ridiculous comedy and cartoonishness. Snooty asides to American Western films and directors are also made. Sergio Leone himself had a major hand in the film’s development and lent his hand in the interesting shootouts that take place in the film.

Telling a simple story of Beauregard, an aging gunslinger who only wants to retire but is constantly pursued by ruffians who want to best him at his own game, teams up with a younger gunslinger who has grown to idolize Beauregard. Based on the adage that “nobody” is faster than Beauregard, the young gunslinger adopts the name “Nobody” and becomes a sly yet brutal fighter himself. The two take on the Wild Bunch, a group of mercenaries working for a corrupt gold baron.

The film is rife with references to previous Spaghetti Westerns, parodying the already over-the-top tropes of shooting multiple bullets through the same hole, taking on overwhelming numbers without a scratch, and lengthy zen-like buildups to explosions of violence much like kung fu or samurai films. It is an oft-overlooked work, but a perfect definition of a Western Comedy.

7. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974) – Sam Peckinpah

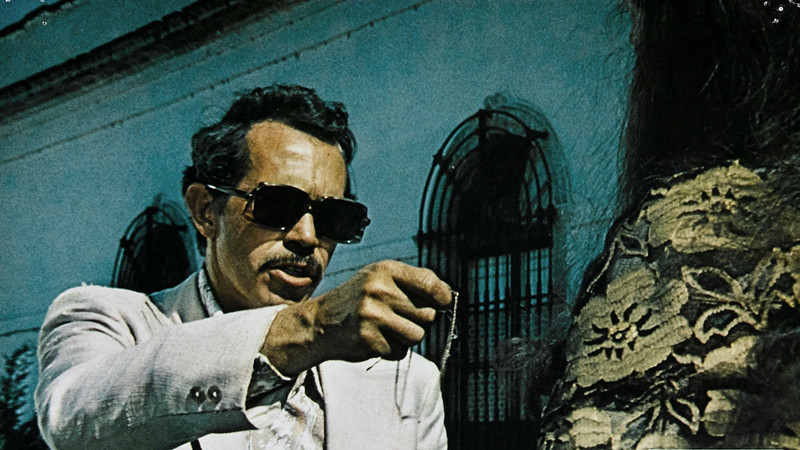

Already a key figure in Western films, Sam Peckinpah instead modernized the Western hero as a troubled alcoholic soldier-for-hire in a contemporary setting. This New Hollywood gem was heavily criticized upon its release for being too violent, too nihilistic, and most of all, too depressing.

After a Mexican drug lord find out his daughter is pregnant, he puts a bounty out on the child’s father, Alfredo Garcia’s head. The problem is, Garcia is already dead unbeknownst to the drug lord and many of the bounty hunters on the search. What follows is an ultra-violent yet poetic adventure going through the deserts of Mexico to small villages to lavish mansions where no one is safe from death.

The casting of Warren Oates as Bennie, was a good choice as he plays the character with tragic grittiness and sheer brutality once he has been forced to accept the chaos of finding Garcia and presenting the drug lord with his severed head.

Despite the fim’s violence and contemporary setting, Peckinpah was able to create a modern Western on a low budget with a unique plotline, exploring similar formulaic introspections and motivations seen in classic Western films. Tommy Lee Jones also played on this notion 30 years later with The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada.

8. Heaven’s Gate (1980) – Michael Cimino

A perfect example of a great movie made at the wrong time, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate was a death sentence on his career and New Hollywood Cinema alike. Gratuitously expensive, insanely over-ambitious, and exhaustively lengthy at 216 minutes long,

Heaven’s Gate actually presents a debunking of a Western tale immortalized by folk legend. Instead, Cimino offers little romanticism in his version of the Johnson County War in Wyoming where European immigrants faced oppressive violence and subjugation at the hands of corporate contractors and land barons.

Part of this film’s initial failure was due in part to the costs involved in the film’s production. However, this film was heavily criticized upon its release for its representation and treatment of America’s proud history.

This film portrays the folk heroes as gangsters and enacting a lawless genocide on an immigrant population that was rebuilding everything with their bare hands. The film is not without its moral arguments as well, featuring friends and enemies collaborating with each other, finding common ground, and choosing sides in a brutal fight for one’s rights.

The main component in this film is its merciless and unglamorized violence. Much like Cimino’s earlier effort, The Deer Hunter (1978) and Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian (1985), Heaven’s Gate presents a full on argument and critique of the men that helped “build” America. Turning the attention to the blood-soaked soil rather than the sprawling cities that eventually sprang forth.

9. Unforgiven (1992) – Clint Eastwood

One of the finest examples of the debunking of the Western myth comes from one of the masters of the genre himself. Clint Eastwood’s masterpiece has been considered the last true Western by many, yet its approach differs from most Westerns that have gain classic status. Much like Shane and McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Unforgiven focuses on the history of a character and uses it as a main plot point.

Hired to collect a bounty on two cowboys who cut up a prostitute’s face due to a misunderstanding, aging farmer William Munny picks up his gun after eschewing violence to bring the outlaws to justice. Along with another aging friend and an overzealous youngster, the trio must face off against the town’s sheriff, who doesn’t want violence to greet his town. And he will do anything to ensure this does not happen.

One of the main ways Eastwood flipped the genre on its head with this film is by casting himself in the lead. Not as a hero or softspoken gunslinger, but a man living with his own violent demons that he has put behind him. Dismissing most of his adventures as whiskey-fueled regrets, Eastwood portrays William Munny with a melancholic demeanor, ultimately shattering Eastwood’s own legendary status as a Western star.

The second main example of Unforgiven’s inversion of Western archetypes is that essentially the audience is rooting for the bad guys in this film. From a classic standpoint, an audience would view William Munny as a villain, ready to kill for money while the town of Little Whiskey’s sheriff Little Bill (played by Gene Hackman) upholds the law and prevents death and destruction from befalling his town. Instead, Little Bill is the brutal antagonist while Munny is more or less a victim.

Little Bill acts as a personal debunker of myths by telling the true stories behind certain gunslingers, ultimately crushing their legendary status in the public, while Munny dances on the edge of a razor, trying desperately not to turn back into the monster he once was.

Winning the praise of many fans and critics, Unforgiven is indeed a swan song to the Western genre, especially in an era where the action movie reigned supreme. Eastwood manages to tell a bulletproof story relying on just the right amount of action and grittiness to make it a full-fledged Western cinema classic.

10. Dead Man (1995) – Jim Jarmusch

Indie cinema in the 1990s is a topic often discussed in most film circles, and its treatment of the Western was not commonly seen in said decade. Jim Jarmusch came along and produced a bizarro-Western with an impressive cast and postmodernist agenda. Deemed “psychedelic,” the film is a mishmash of many different elements.

Featuring a soundtrack by Neil Young, Robby Müller’s cinematography draws on the landscape photographs of Ansel Adams, the motley crew cast ranges from veterans like Robert Mitchum to indie film regulars like Michael Wincott and Jared Harris to superstars like Johnny Depp. The film also includes a culturally adept treatment of Native Americans in a genre that usually paints the culture as savage and otherworldly.

Being a postmodern film, Dead Man’s narrative is scattered, much like other postmodern works of the time like Pulp Fiction (1994). The basic story is about William Blake (Johnny Depp), a bumbling accountant who arrives, and is promptly run out, of the Gotham City-like town of Machine.

With two deaths on his hands (one he is innocent of, the other self-defense), and a bullet in his chest, Blake goes on the run through the wilderness to escape the wrath of the factory owner whose son Blake killed. Along the way, he befriends a mysterious Native American Indian named Nobody who attempts to help him.

The well-versed Nobody tells Blake that the bullet wound is fatal and that he is in fact a dead man walking. Being that William Blake is named after the apocalyptic poet from the 18th century, Nobody believes Blake is the reincarnation of the poet, only now his works will be written in blood. Along the way the two meet an array of cutthroat villains who contribute to William Blake’s violent descent into murder.

One of the first black-and-white Westerns to emerge since the 1960s, Dead Man has a lot of referential chops while staying true to its own story. The characters are psychologically inaccessible yet contain their own unique quirks that distinguish themselves among the film’s large cast. Not necessarily well-liked by audiences, Dead Man is a divisive film, yet its poetic approach is of similar surrealist nature to Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970).