While not as flashy as the most celebrated auteurs of today, whenever Alexander Payne releases a new film, it is a worthy event for cinephiles. As a director working in the realm of dramedies that are equally humorous and downbeat, Payne, whose new film, “The Holdovers,” has been nominated for Oscar Best Picture this year, specializes in a class of films that are reminiscent of a previous generation.

When critics lament “they don’t make these kinds of movies anymore,” this generalized body of movies is representative of Payne’s filmography. The director brings a unique vigor to adult-oriented, human dramedies about aging, companionship, and self-reflection. On the exterior, his films come off as milquetoast, but his acidic humor and melancholic streak push the limits of what audiences expect from mid-life crisis road-trip comedies. Here are all of Alexander Payne’s films ranked.

8. The Descendants (2011)

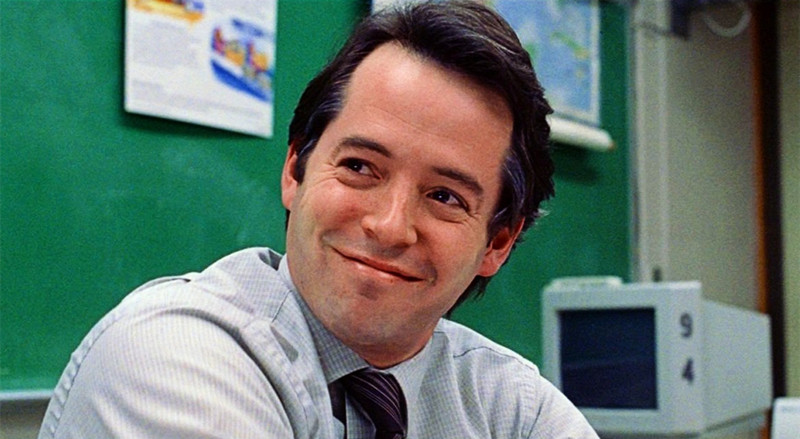

Alexander Payne solidified his status as one of the best working directors in Hollywood following his golden age in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, which was capped off by “Sideways.” During perhaps his creative prime, he disappeared from the big screen for seven years. He promptly returned to critical acclaim and recognition from the Academy Awards with “The Descendants” in 2011. While the consensus at the time regarded this film as quintessential Payne, it holds up the least within his filmography, as it strives for the traditional beats of dramedies about middle age and family in the form of a star vehicle for George Clooney.

“The Descendants” follows a lawyer, Matt King (Clooney), a lawyer based in Hawaii who is conflicted by the pressure to sell his family’s valuable land trust in the wake of a boating accident that leaves his wife in a coma. He uses this unfortunate predicament to rekindle with his daughters Alex (Shailene Woodley) and Scottie (Amara Miller). Each performance is authentically lived-in and vulnerable, which is on par for a Payne film. Clooney, in particular, who received a nomination for Best Actor, allows his glamorous star persona to be stripped down in favor of exposing his character’s lonely soul and lack of insight into his surroundings. A careful eye for location is an essential trait of Payne’s, as his appreciation for Hawaiian culture and the natural beauty of the land is evident in “The Descendants.”

However, the emotional core of the film, involving a man shaking out of his monotonous life and preparing his daughters for the tragic death of their mother, is surprisingly tepid. Payne, who expressed in an interview recently that too many movies extend their welcome in the runtime, directs his films with a propulsive pace. With “The Descendants,” however, the pacing is sluggish, and it never leaps off on the right foot. Where his other films are unafraid to lean into absurdist humor or the darkest pockets of his characters’ emotional angst, “The Descendants” continuously operates in vacant territory. By no means is the film of poor quality. It routinely hits the right beats of a serviceable comedy and drama, but compared to the rest of the Payne oeuvre, it is noticeably ordinary.

7. Citizen Ruth (1996)

Alexander Payne’s debut film appears as an outlier in his filmography, but when mirrored with his follow-up, “Election,” the pathway to him being the great satirist of his generation is foreseeable. While this thematic trait has faded away in his cinematic arsenal over the years, Payne is interested in scathing critiques of society and politics. In particular, he has an affinity for juxtaposing harsh political satire with the backdrop of an innocent setting. Payne’s rich storytelling was announced to the public in 1996 in his prescient political satire, “Citizen Ruth.”

The film stars Laura Dern as a drug-addicted and impregnated woman, Ruth Stoops, who becomes entangled in a fiery birth control debate in her town after a judge orders her to get an abortion or else she’ll be facing a felony charge, with both sides soliciting her as a totem for their respective argument. In the film community, Payne is rarely associated with his contemporaries who emerged in the ‘90s indie boom, including Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, and Paul Thomas Anderson. He would go on to make films that run counter to these auteurs who have developed their unique worldviews. “Citizen Ruth” belongs to this underground filmmaking movement, as it taps into a counterculture inspired by the films of New Hollywood. Payne’s filmmaking infancy presents him as a more visually aggressive director looking to subvert the medium, where in his later years, he found a middle ground that used a familiar cinematic template while still retaining his voice.

Like many debut features, “Citizen Ruth” is raw. Payne’s future films will all be more focused. It is evident that Payne’s heart is in Ruth’s character. Tracking her as an individual belonging to the lowest rung of the class hierarchy who suddenly vaults to political prominence is a surefire way to develop a character and comment on the spontaneity of public influence. Payne’s fixation on this enticing concept muddies the usual dissection of loneliness and angst that are present in his best films. His sardonic tone that was perfected in “Election” prevents Ruth from being one of Payne’s most expressive characters. Nevertheless, “Citizen Ruth” is a justified scathing critique of how political discourse alienates marginalized people. In this case, the stifling of a woman’s voice regarding her right to choose is especially damning.

6. Downsizing (2017)

The ultimate outlier of his filmography, Alexander Payne used his cachet after years of being celebrated by critics and awards bodies to step into the vast field of science fiction. Along with his venture into uncharted territory, Payne sought to combine his skill for humanist dramas with his eye for social satire to produce his most ambitious film to date, “Downsizing.” Critics and audiences were not enthralled by the director’s ambition. The film became a major critical and commercial flop. While the flagrant criticisms are valid, “Downsizing” is a misunderstood film with an uncharacteristic tone and vision that deserves a second look.

Payne’s sci-fi dramedy tells the story of Paul Safranek (Matt Damon), who chooses to partake in a scientific breakthrough where his body is shrunk to a microscope size to live a life of wealth and splendor in an experimental community. His wife, Audrey (Kristin Wiig), backs out at the last minute, leaving Paul alone to befriend a Vietnamese activist, Ngoc, (Hong Chau). The flow and narrative structure of the film is jarring, which may explain the dismissal it received from audiences.

The opening act is quintessential sci-fi world-building, complemented by a dramatic arc of a financially struggling married couple looking for an escape. Then, the story pivots to a fish-out-of-water story of Paul just trying to survive in this bizarre downsized world. The third act is unexpectedly minimalist, shifting into a traditional Payne film about kinship between two lost souls. While unconventionally paced, “Downsizing” has a mind of its own, and it refuses to conform to genres.

Reclaiming “Downsizing” as a flawless masterpiece is impossible, as the flaws are apparent. The third act, while ambitiously forgoing its sci-fi labyrinth environment, loses the social edge of its commentary that the story was founded upon. The chemistry between Damon and Chau is a breakthrough, and the character dynamics between them are intriguing in concept, but, in execution, the relationship is lackluster in energy. Furthermore, the treatment of Ngoc, a persecuted activist by the government, is dealt with in a patronized manner by Payne. The dazzling universe created by Payne is impressive for a non-genre filmmaker. Considering that he abandons his sci-fi elements, the world takes on a superficial purpose.

On the contrary, transforming the downsized world into one that mirrors reality is an argument that Paul cannot escape his issues of trust, no matter what universe he belongs to. In context to the woes of Ngoc, his traumas pale in comparison, which is a sobering act of reflection on Payne’s part. At the very least, it is hard to deny the inherent wonder and mystery of the opening section of “Downsizing.”

5. Nebraska (2013)

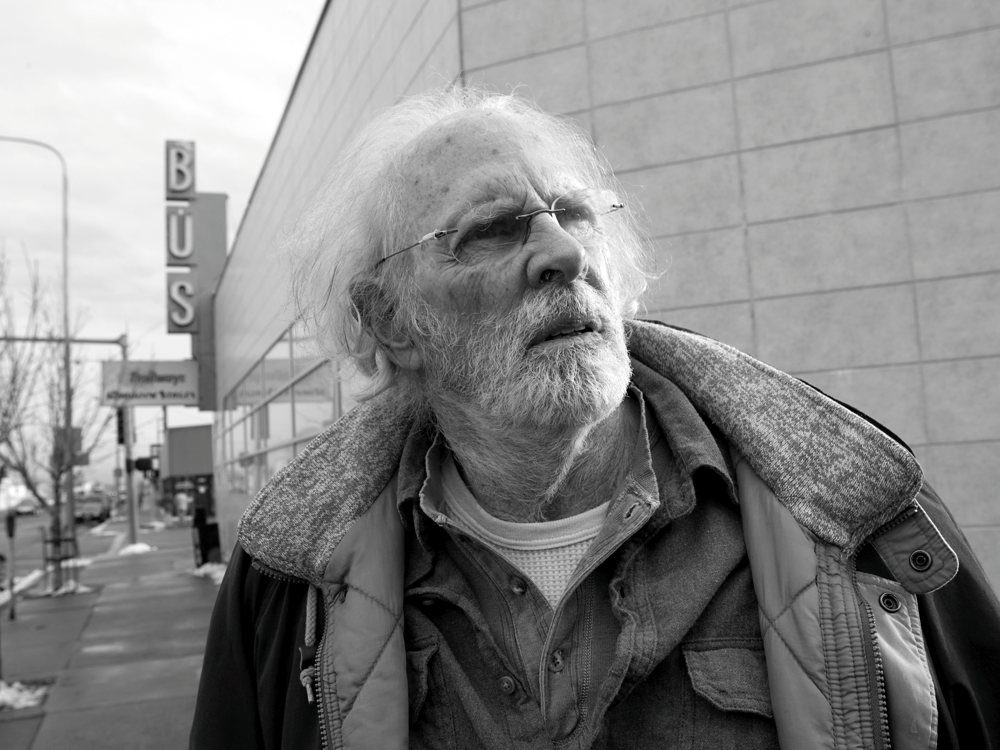

Nebraska, the state of origin for Alexander Payne, has been a fabric of Payne’s work in the past. His fondness for its milieu of working-class folk and the open vistas along the countryside served as the heart of his 2013 film, “Nebraska.” At perhaps the apex of his critical and awards acclaim, Payne continued to operate in familiar territory but directed the story of a road trip between a father and son with just enough pathos and inscrutable character motivations to make it stand out and express the director’s voice as an auteur.

“Nebraska” tracks an elderly, booze-addled father, Woody Grant (Bruce Dern), who embarks on a cross-country trip with his estranged son, David (Will Forte) to claim a million-dollar Mega Sweepstakes Marketing prize, and to settle some differences in his titular home state. Following the more saccharine turn in “The Descendants,” Payne reclaimed his acidic edge in his third film to be nominated for Best Picture.

The black-and-white photography appeals to this tonal decision. Beyond the defined visual aesthetic, the cinematography adds a discernable emotional resonance that suggests an aimlessness involving the complex relationship between Woody and David. Not only are the two entering an unknown void in this journey, they are venturing into a world that is lost to the past. Woody’s return to his hometown to settle lost scores is both an act of desperation and a cleansing of the soul. Payne relishes in the uncertainty in “Nebraska,” as the film presents some of the director’s finest practices of ambiguity. For the viewer, the alluring charm between Woody and David, gorgeous photography, and intimate character studies take them along for the ride regardless of the unclear motivations.

Payne’s unique tone, one that perfectly infuses expressive comedy with a downbeat meditation on purpose and aging, is exquisitely realized in “Nebraska.” There is a dual complex to his equal parts admiration and ridicule of the extended Grant family. Despite the film being penned by someone else, Bob Nelson, “Nebraska” is pure Payne, even if it radiates as a reductive work in instances.

More so than any of his other films, his 2013 film closely examines how men of differing generations and attitudes can relate to each other through their past failures and regrets. David can see himself morphing into Woody, the absentee father who could never bond with his son, but by enabling his father’s indulgent fantasy of winning a phony promotional giveaway, he slowly discovers that life can still contain a vigorous spirit in one’s later years. “Nebraska” is a fitting inflection point in Payne’s career. His cynicism has waned–sensing some merit in the idea of redemption. However, one can only grow through matters of cumbersome self-reflection.