In more ways than none, Steven Spielberg is synonymous with the art of film directing. Not only is his commercial success unparalleled, but he is also responsible for some of the most iconic films, characters, images, and thematic ideas of Hollywood history.

In essence, Spielberg is the ideal filmmaker, equally populous and crowd-pleasing as he is intelligent, groundbreaking, and artistically sound. Everyone knows the classics, but Spielberg, who has directed over 30 films throughout his illustrious career, has underseen and overlooked gems in his reservoir.

1. Duel (1971)

Watching a significant director’s debut film in retrospect of the current context is always fascinating, especially when the seeds of their artistry were intact. While merely a T.V. movie, Duel is the definitive blueprint to Jaws, as well as the masterful staging and viscerally accessible entertainment that Steven Spielberg perfected. The film has become an object of cult fascination over the years, and it is the Rosetta Stone for how Spielberg emerged as the populous voice of a generation.

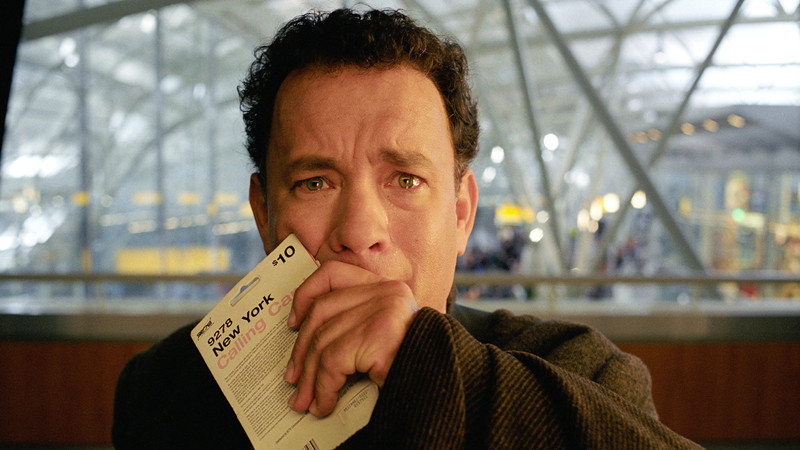

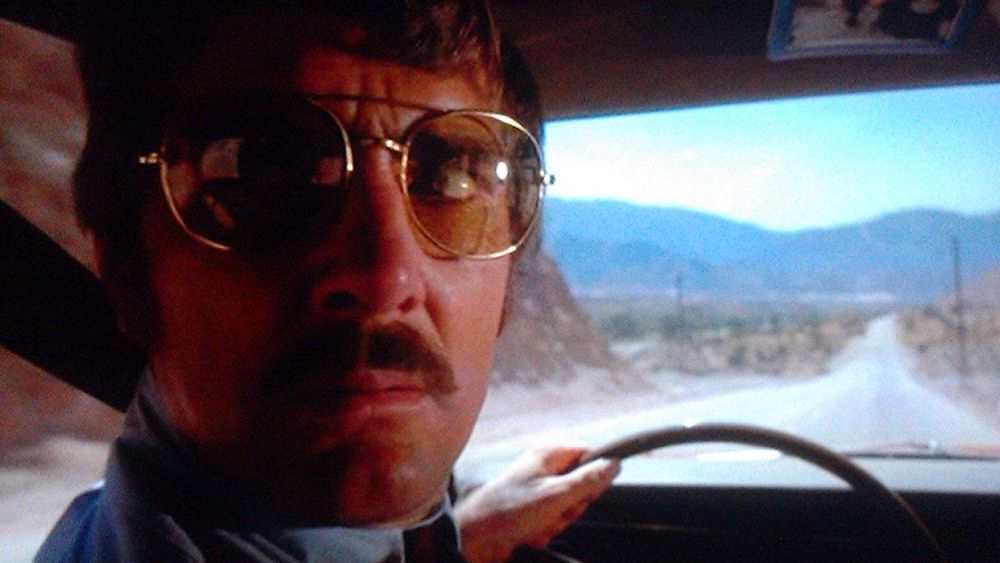

Duel follows a business executive, David (Dennis Weaver), who commutes to an appointment with a client when an ominous truck driver terrorizes him during his trip. The truck continues to chase after him on the road, and David is forced to drive for his life. Plot-wise, Duel mirrors the crux of Jaws. Other stylistic and thematic elements, such as the elevation of trashy B-movie material and the fear of the enemy being the dramatic device rather than the entity itself, lends the 1971 TV movie as the true predecessor to the summer blockbuster. The truck driver, and even the truck itself, remains a faceless figure lacking any tangible motivation throughout, which only heightens the treacherous stakes.

Once the frantic cat-and-mouse game between David and the truck ignites, Spielberg never figuratively lets his foot off the gas. The accelerated momentum of Duel is too rampant for the small screen. On a textual level, the film utilizes the desert setting to, perhaps implicitly, exploit the dynamic of a white-collar, suburb-dweller trekking out to the frontier and confronting the danger of the wild west. Whether or not this is designed to comment on a sociological phenomenon, this juxtaposition further adds to the thrills and cinematic bliss of Duel.

2. The Sugarland Express (1974)

His arrival on the big screen, this early work is not as omnipresent with the traditional Steven Spielberg DNA. Indebted to New Hollywood films about outlaws on the run, The Sugarland Express is a downbeat spin on the director’s exploration of family and adventure, and the integration of classic Hollywood figures and ideas into a modern world. While Spielberg pivoted in a different direction, films of this limited scope could have boded well for his artistic craft.

In The Sugarland Express, Lou-Jean (Goldie Hawn) and her husband Clovis (William Atherton), who recently escaped from prison, are on the run from the law after taking a police officer hostage in their attempt to kidnap their child from foster parents. The film may remind audiences of counterculture road movies like Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider on the surface, but Spielberg’s formative expressive camera movements and explosive action set pieces offer something slightly more palatable.

If anything, The Sugarland Express demands more attention to the psychology of broken people. Spielberg is perhaps too committed to testing his abilities as a director of spectacle. Because of this, however, he proactively discovers ingenious ways to shoot the most rudimentary sequences. Every angle, shot length, and framing device is employed by Spielberg.

His admiration for Westerns and the filmography of John Ford is evident in the casting of Ben Johnson and the characterization of powerful lawmen at the end of the line. If The Fabelmans reminded Spielberg and his audience anything, a shot comprised of a horizon in the middle of the screen is, described by David Lynch’s portrayal of Ford, “boring as shit.” The Sugarland Express laid the groundwork for Spielberg as a wondrous visionary.

3. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984)

For some baffling reason, Temple of Doom has been subjugated as part of the “bad Indiana Jones” films alongside Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. While the 2008 Indy comeback film is ripe with flaws, the 1984 sequel pushed the envelope for franchise filmmaking and the MPAA rating board. Spielberg uses a bankable franchise and beloved character to vault towards deranged filmmaking that he never aspired to before.

The Temple of Doom is set before the events of Raiders of the Lost Ark, following Indy’s (Harrison Ford) quest to reclaim a rock stolen by a secret cult lurking beneath the catacombs of an ancient palace. It is refreshing to watch a prequel that isn’t relentlessly bogged down in expanded universe lore, or panders to fanbases regarding a favorable portrait of the central character. Furthermore, the plot of the film is superfluous. Spielberg is focused on incredible spectacles and dazzling set pieces. Temple of Doom has an escalation and momentum that boosts tension and the livewire character dynamic between Indy, Short Round (Ke-Huy Quan), and Willie (Kate Capshaw).

The film mimics its own minecart chase, never slowing down until the closing credits. Spielberg sees no creative boundaries with his film, as he gleefully leans into both horror and slapstick comedy, with the former of the two being so pronounced that the PG-13 rating was implemented thanks to the movie. The film’s depiction of Southeast Asian people is slightly problematic, to say the least, but all of these indelible facets of Temple of Doom highlight how bold and daring Spielberg was at the time. He easily could have phoned in an Indy sequel just for the paycheck, but he chose to up the ante by giving the character a gonzo treatment.

4. Empire of the Sun (1987)

The mid-late 1980s saw Steven Spielberg, perhaps at the height of his popularity and commercial success, chasing after an Academy Award by tackling serious “adult” stories. The films of this time, including The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun, are still embedded with his sense of wonder and hopefulness in the face of danger. With his latter film in 1987, Spielberg got his first taste of a historical epic about the immense gravity of political turmoil, all through the perspective of a child, in Spielberg fashion.

Empire of the Sun centers around a young English boy, Jim (Christian Bale), who struggles to survive under the Japanese occupation of China during World War II. An expert in directing child actors, a young Bale is a perfect match for Spielberg. He has a delicate touch regarding elevating children to make them sympathetic and relatable to adults. Following this story with lofty stakes from young Jim’s eyes is seamless. Despite being a film about wonder and sentimentality amid a national crisis, Spielberg displays a remarkable amount of restraint from his typical wonder and sentimentality. In this case, Empire of the Sun relies on natural emotional manipulation.

For better or worse, the film is usually leveled and doesn’t give into monumental payoffs, especially in the first half. The section before entering the internment camp contains some of the most harrowing sequences and imagery of the director’s filmography, as the despair of war-torn China correlates with the inherent danger of shattered innocence. Empire of the Sun operates as a transition phase for Spielberg, as he juggles the wholesome quest for hope against a dire historical context later seen in Schindler’s List and Lincoln.

5. A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

In 2001, Steven Spielberg was handed the impossible task of completing an unfinished project by the recently passed Stanley Kubrick. Two directors with seemingly counterintuitive artistic and thematic styles would converge to produce A.I. Artificial Intelligence, a science fiction riff on Pinocchio. What was criticized at the time for muddling the cynical outlook of Kubrick as a result of Spielberg’s hopefulness is in actuality one of the soulful and sobering depictions of humanity of all time.

In a dystopian future, where A.I. is set, a highly advanced robotic boy, David, (Haley Joel Osment) vows to become real to inspire the love of his human mother (Frances O’Connor). Kubrick’s imprint on the narrative is inseparable, but make no mistake, this is Spielberg’s alluring vision. The film’s distinct three-act structure gives it a sprawling scope. Some cite this as messy storytelling, but Spielberg’s exploration into how advanced technology only suppresses the hearts of broken natural and artificial life forms across various walks of life is magnetic. A.I. expertly walks a fine line between the bleak distortion of artificial life and longing for human affection remarkably.

There is an unnerving dreamscape to A.I. that mirrors the moral quandary of the future of artificial intelligence that lingers today. The characters, environment, and feelings are all familiar, but they are ultimately impenetrable. Basic human core values, love, companionship, and trust, all are muddied in this universe. The paradox surrounding the manufacturing of affection is met with an inevitable reality of David, a programmed robot, doing whatever it takes to satisfy its coded definition of becoming a real boy. On the surface, the film’s ending is a tiring illustration of Spielberg’s sappiness, but only in a subversive reading does it conclude that artificiality clouded as blissful reality is the cruelest form of closure.