At the 2019 Oscars, Roma (2018) – Alfonso Cuaron’s semi-biographical, Mexican-language film – equalled the record for the most Oscar nominations by a film not in the English language. With 10 nominations in total (including Best Picture), it went on to win Best Achievement in Cinematography, Best Achievement in Directing, and Best Foreign Language Film.

Bong Joon Ho’s film, Parasite (2019), followed Cuaron’s benchmark brilliantly at the 2020 ceremony, going onto win Best Achievement in Directing, Best Original Screenplay, and being the first South Korean film to win Best International Feature Film. Crucially, though, Parasite also became the first ever film not in the English language to win Best Motion Picture of the Year – a momentous, overdue achievement.

2020 boasted, as many years do, a tremendous variation of international cinema more generally, too. Take Honeyland (2019), for example, a passive yet tender North Macedonian film nominated for Best Foreign Language Film along with Parasite, as well as Best Documentary Feature. Or, of course, Pedro Alomodovar’s heart-wrenching and beautifully personal Pain and Glory (2019) which also stood side-by-side Parasite and earned Antonio Banderas his first ever Oscar nomination.

There is also Poland’s Corpus Christi (2019), or France’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019), or Portugal’s Vitalina Varela (2019), or China’s So Long, My Son (2019) – to name a small few – that have recently been released and amassed large critical success. Director Bong Joon Ho, in his acceptance speech at the Golden Globes, urged audiences to “overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles” in order to be “introduced to so many more amazing films” and the aforementioned list is a great advertisement for that sentiment.

Parasite’s Best Picture win marked a significant moment in cinema and award history, and is one that hopefully opens up avenues for more diversity at the forthcoming Oscars and a wider acceptance of international cinema generally. By taking Parasite’s example, then, here we look at other films that won Best International Picture since the category’s inception in the 1940s, illuminating a breadth of great international cinema classics.

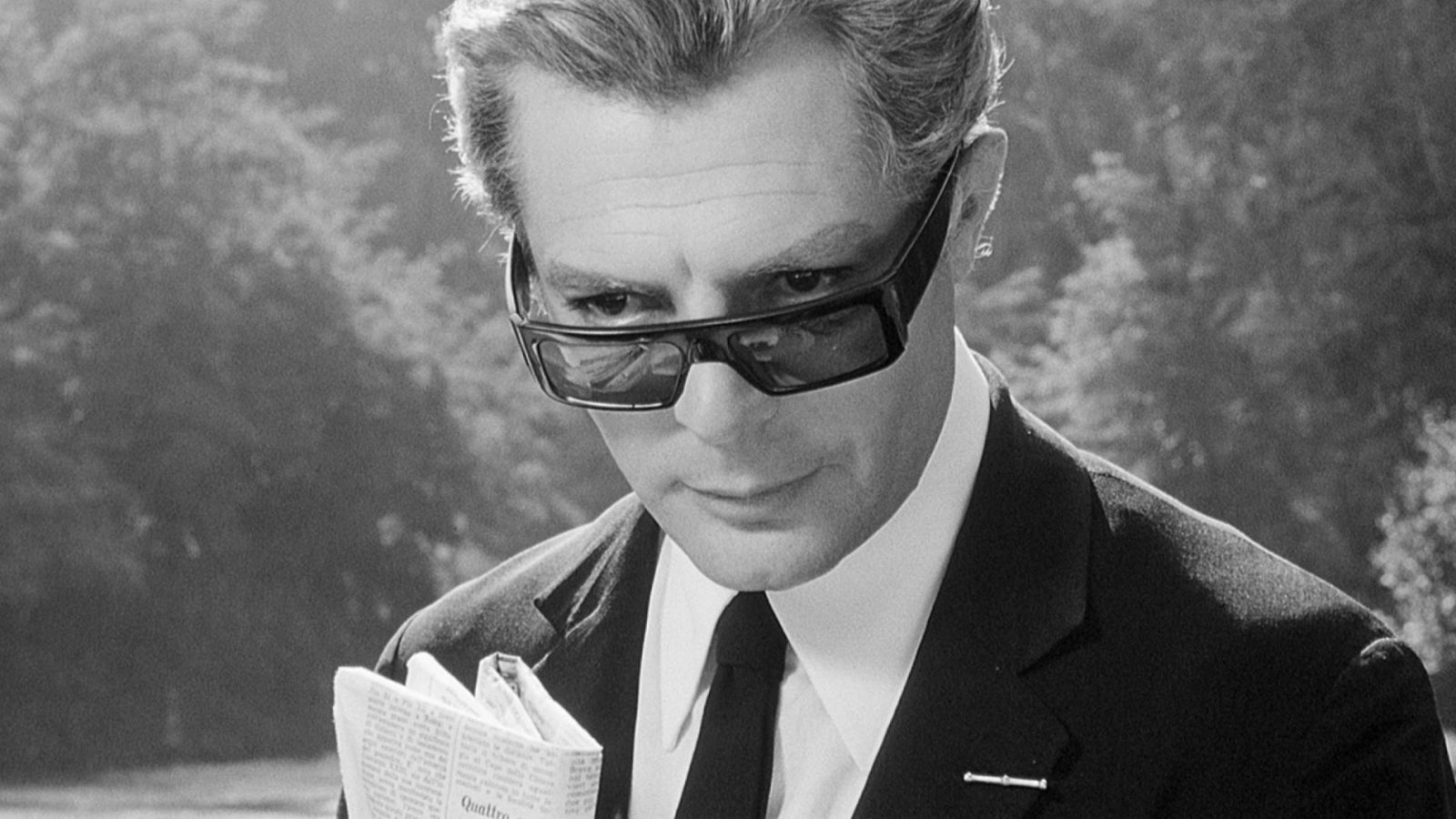

10. Mon Oncle (Jacques Tati, 1958)

French filmmaker Jacques Tati moulded his career around physicality and performance art and his films were often reminiscent of the work of Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, or Charlie Chaplin in its use of slapstick comedy and wit. Tati was one of the few filmmakers that managed to bridge sound cinema with the silent era, using gesture and movement as his principal film language.

In Mon Oncle, Tati uses this slapstick, comedy-of-errors style to tackle modernity and the growing post-War obsession with consumerism. The world is meticulously designed with automatic garage doors, large, reflective water features, and brutalist sculptures that would give any science-fiction film that followed it a run for its money.

At the heart of the film is Tati’s lovably bumbling Monsieur Hulot as he humorously contends with new trendiness in an often disastrous manner. Hullot may be foolish but he is ultimately likeable and endearing in ways that those around him are not. He is someone who is attentive and kind to others – whether that be by collecting his nephew from school or gifting an apple to a girl who lives nearby – where others would rather pander to public expectation.

While Tati probably mastered this style in his later feature films, Playtime (1969) or Trafic (1971), it was Mon Oncle that won him the coveted Academy Award for the Best Foreign Language film, and deservedly so.

9. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

Bicycle Thieves is probably the most recognisable title to come from the Italian Neorealist movement of the 1940s and 50s. A precursor to the French New Wave, Kitchen Sink Realism, contemporary contemplative cinema, and many more, the Neorealists sought to find authenticity and truth via the means of narrative filmmaking. Forced against political writing and in a post-War period where Italian filmmaking was teetering on a knife edge, the Neorealists used innovative techniques like on-location filming, natural lighting, and non-professional actors. Many of the films to come out of the movement interrogated the conditions of the poor, their characters usually being working class or out of work completely.

Bicycle Thieves employs these characteristics and brings the Neorealist style to a head. In a documentary vein, it holds a mirror to the harsh Italian, post-War landscape that is laden in poverty, homelessness, and destitution. It is a simple story of a man’s search for a job, of which comes in the form of a bike that gives him transport to become one of the cities’ poster-hangers. On the job, though, he has his bicycle stolen, leaving him on a gruelling and endless hunt for his only means of income with little hope in sight.

Bicycle Thieves is an understated yet moving account of a man and his son’s struggle with poverty and one that is a landmark in post-War cinema. Its lasting legacy continually proves that it is an undeniably inspirational and magical work of cinema and was only the third film ever to win in this category – an honorary award in 1950 for the Most Outstanding Foreign Language Film.

[side note: Bicycle Thieves was marvellously adapted in 2001 in Xiaoshuai Wang’s Beijing Bicycle; updated, retextured, and placed into a new geographical context, Wang creates another beautiful piece of work that is definitely worth your time.]

8. Black Orpheus (Marcel Camus, 1959)

French Director Marcel Camus came to prominence with his first Brazilian-themed film, Black Opheus (or Orfeu Negro), that won the 1959 Palm d’Or and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Black Orpheus is a reimagining of the Orpheus and Eurydice Greek myth, beautifully and vibrantly re-contextualising the story around the Rio de Janeiro Carnival. Doing so, Camus reinvents the story with stark imagery, colourful dance sequences, and a joyous, rapturous soundtrack that elevates the love story into something more spiritual.

Here Orpheus (Breno Mello) is a streetcar conductor, loved by his favela locals because of his beautiful singing and his ability to raise dawn from his guitar playing; Eurydice (Marpessa Dawn) is a country girl visiting Rio for the first time, lost in the bustle of Rio’s vivacious Carnival atmosphere. They meet by chance on the streetcar and Eurydice is overcome by Orpheus’ musical talents. Much like Eurydice, we are also overcome and treated to a colourful musical score and one that gave birth to the Latin American pop sound, “bossa nova.”

What is essentially a tragic love story, Camus manages to balance heartbreak with energy and joy. Notably, Orpheus’ time in the underworld, cleverly imagined here as Rio’s Lost Person Department in an empty police station, is truly heart wrenching. Camus follows the film’s tragedy, though, with moments of hope and joy whereby young admirers of Orpheus continue his ethos of song and dance, so that even in moments of pain the overriding love for music endures.

7. A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, 2011)

Asghar Farhadi’s first success in this category, and ultimately Iran’s first win too, came with his gruelling yet socially poignant film A Separation – only to win again a few years later with The Salesman (2017).

A Separation centres on two parents who both want the best lives for their family. Simin (Leila Hatami) wants to leave Iran for a more liberal country, giving her daughter a freer life; Nader (Payman Maadi) wants to stay in order to care for his elderly father who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. The two’s disagreement forces upon them an unwanted divorce which sees Simin leave to stay with her mother. The question then asked is: how does Nader continue leading his working life without a wife in the house? The film’s answer is a tough test of strength as Nader is then accused of manslaughter by the husband of his in-home carer who claims she had a miscarriage after she was pushed when Nadir fired her.

A Separation is a difficult yet engrossing watch as its moral examination becomes an emotional hook. Every character, here, tries to do good and each have justified motives but ultimately not everyone has all the facts. The endeavour for moral good, then, causes confusion and conflict, making even the most fractured of lives even more agonising.

6. 8 ½ (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Along with the Neorealists (De Sica and co.), Fellini was another name that recurrently cropped up winning in this category during its earliest incarnations. Both La Strada (1954) and Nights of Cabiria (1957) are worthy of being mentioned here, though it is Fellini’s masterwork, 81/2, that stands out from the bunch.

Repeatedly seen topping many critics lists of the greatest films ever, 81/2 follows fictional film director Guido Anselmi (played brilliantly by Marcello Mastroianni as a Fellini stand-in). A film about creative stagnation, Guido travels to a luxurious spa in an attempt to reinvigorate his inspiration to complete his latest science-fiction epic – a film being hailed as his next masterpiece. Followed by his lover and then his wife, Guido tries (and mostly fails) to balance the film world of producers and actors with his personal life, at once confusing the two yet finding solace and happiness among the difficulty of a fragmented life.

A beautiful mix of truth and lies, reality and dream, honesty and adultery, Fellini carves out the most salient depiction of the film industry by brilliantly blending fiction with autobiography.