5. The River (1951, Jean Renoir)

As is the case with many other directors cited on this list, Jean Renoir proved that, even in the tail end of his career, he still had ample curiosity about the world and an even richer desire to explore new aesthetic possibilities when he made “The River.”

This movie represented many “firsts” for the filmmaker: his first to be produced outside both France and the US; the first to star mostly non-professional actors; and, most notably, the first film he shot in color. But aside from the particulars of Renoir’s own career, it was also one of the first mainstream movies made in the West to be set in India (and it was actually filmed there on location).

In fact, over time, “The River” has been accused of being a colonialist fantasy, and though undoubtedly the story is told through a firmly outsider’s perspective, it never commits any of the common mistakes or offenses that white filmmakers fall into when portraying a different culture. The movie never “otherizes” the Indian people, nor does it treat their traditions as a strange, exotic thing; there’s tremendous respect and naturalism in the observation of their way of life.

Martin Scorsese said this was, along with “The Red Shoes,” the most beautiful color film ever made, and it’s hard to disagree with him: Renoir used Technicolor to highlight the gorgeous landscape of the country with its bright green vegetation, perfectly complementing the director’s methodical compositions (his father would’ve been proud).

In direct contrast to the last two movies of this list, “The River” is extremely light on plot; it has a very free-flowing structure that frequently cuts away from the main narrative for atmospheric flourishes (there’s even a napping montage at one point). But that’s very purposeful: Renoir uses the meandering nature of the movie to comment upon the cycles of life itself, of birth, death, and rebirth.

4. The Man Who Would Be King (1975, John Huston)

The late period in any director’s career can often be, as stated throughout this list, an arduous creative time, be it for lack of interest from the public, difficulty finding funding, or just downright personal failure in reaching the same heights of their youth. However, for some more fortunate filmmakers, the final stretch of their lives can finally mean getting their dues after a lifetime of hard work; a renewed opportunity to get their dream projects off the ground – as, for example, Scorsese did recently with both “Silence” and “The Irishman.”

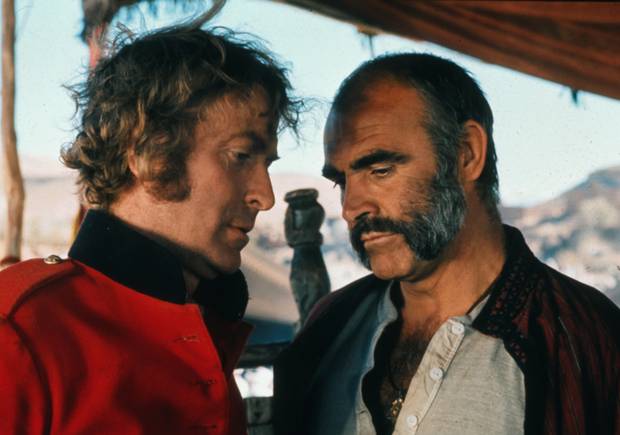

Such was the case as well with John Huston, who spent decades trying to make “The Man Who Would Be King,” being fascinated with the story since first hearing it as a child. He finally got his wish in 1975, when his adaptation of Richard Kipling’s novella of the same name came out. The story follows two former officers of the British Army (played by Michael Caine and Sean Connery) in 19th century India, who set off to find the land of Kafiristan, a mythical place that no explorer has laid eyes on for centuries. Arriving there, things take a surprisingly positive turn for them – until, of course, their luck runs out.

Huston was a craftsman who could effortlessly alternate between styles, going from cynical, disillusioned, borderline nihilistic dramas to populist escapism, and this movie found him on the peak of the latter. It’s the most entertaining film of his career, and one the most impressive craft-wise, with impeccable widescreen compositions and perfect control over pace and tone.

The fact that it took so long to make is one of those instances in which the long wait was actually a blessing in disguise, since it allowed for Caine and Connery to be a part of the movie. Originally, Huston wanted to cast American actors in the roles, which definitely would have diminished the appeal of the characters; their Britishness is an essential part of how they view the world and behave in it and, thus, a key element that informs their outcome. Plus, Caine and Connery’s electrifying chemistry only makes everything even more entertaining.

3. To Be or Not to Be (1942, Ernst Lubitsch)

Critics and film scholars to this day still debate the meaning of the so-called Lubitsch Touch, a term originally invented by a PR person to turn the director into a brand name, but which eventually gained actual artistic significance. Some say it means a particular visual style of humour and wit; others argue it represents a specific kind of storytelling sophistication and charm. Billy Wilder claimed it meant the use of the “superjoke”; that is, the unexpected joke on top of an already great gag. Whatever its definition, though, everyone agrees there is such a thing as the Lubitsch Touch, a certain je ne se quais that makes his work essential and unique.

Perhaps no movie embodies this Touch (and all its definitions) better than “To Be or Not to Be,” Lubitsch’s phenomenal satire of the Nazi regime. Starring the spectacular Jack Benny and Carole Lombard (in her final film before a tragic plane crash shortened her life way too early), the plot concerns a troop of actors in German-occupied Poland who get involved in a scheme to capture a Nazi spy.

“To Be or Not to Be” is one the most genuinely funny screwball comedies ever made; it doesn’t elicit just timid smiles, but absolute belly-aching laughter. Repeated jokes have rarely been used to better effect than is this movie; every single gag is great on its own, but their sequential use throughout the narrative is brilliant (you will never hear the name Schultz the same way again). And the plotting is key in achieving that humour as well: there are very few movies that can rival this one for tonal balance. Once the espionage story gets going, every scene is simultaneously hilarious but also filled with spine-tingling suspense – two different moods that work not in spite but because of each other, an expertly crafted game of tension and release.

And on top of that, the movie is also a profoundly humane denouncement of the horrors of its time: it was released in 1942, right amid World War II, and never shied away from portraying the humanity of its Jewish characters – and the evil of those who would deny it.

2. Certified Copy (2010, Abbas Kiarastomi)

There’s a tendency nowadays, in mainstream film discourse, to treat all of cinema as a puzzle waiting to be solved; as if there’s one single and unquestionable explanation that would definitively resolve a piece of art. It’s why we have so many “Ending Explained!” type videos proliferating on YouTube. How refreshing and hopeful, then, that a movie like Abbas Kiarastomi’s “Certified Copy” exists, something that not only defies one single definitive interpretation, but builds the entire narrative around the mystery of what is actually going on.

If you haven’t seen the movie, I hesitate to spoil the nature of the plot in here and where the story goes, so suffice to say it begins with a British writer (William Shimell) in Tuscany promoting his latest book, who meets up with a French woman (Juliette Binoche) to go on a tour across the city. From there, in typical Kiarastomi fashion, we accompany their conversations during the drive, which slowly transition from casual acquaintances making small talk into something else.

“Certified Copy” wasn’t exactly the first movie Kiarastomi made outside of Iran (he directed a documentary about Africa and parts of his film “Tickets” abroad), but it was still the first full length feature he undertook away from home – and also one the first to star professional actors. However, these scenery and technical changes didn’t at all affect his particular style, which is on full display here. The naturalistic look at people engaged in philosophical conversations about life and love; the visual exploration of the breathtaking landscape around the characters; and the general interest in the nature of art and how it shapes people’s lives (a theme he explored more famously in his 1990 classic “Close Up”).

What makes this movie special in his canon, considering it features so many of his trademarks, is precisely the ambiguous nature of the story; the surprising turn it takes halfway through and what it reveals, not about the characters, necessarily, but about our own understating of how narratives work; a turn that poses a question that haunts the entire movie as well as the viewer, who will want to return to this again and again in search of the answer for it. The fact we will never be able to truly find it is an essential part of the movie’s beauty.

1. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962, John Ford)

It’s natural, for any artist, having reached old age and artistic maturity, to look back on their young work and reflect upon them, both on a personal level and on the marks it left in the world. With John Ford, those marks couldn’t possibly be any bigger: there is perhaps no single more influential director in the history of cinema, with an incomparably vast imprint on world filmmaking. Proof of it is the fact that Orson Welles reportedly watched “Stagecoach” on repeat while making “Citizen Kane,” and Kurosawa was hugely inspired by Ford’s style when conceiving his chambara epics. And even aside from that, how many other directors can truly say they basically helped to shape an entire genre, as Ford did with the western?

So, what do you do when all that legacy is behind you, when you’ve cemented your place in the history of the medium and transformed into a legend? If you’re an artist of Ford’s caliber, you make “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” a movie that precisely comments upon the weight of legacy and the elemental, complex, human truths hidden behind the myths we know.

The movie begins when revered old senator Ransom Stoddard (played by the incomparable Jimmy Stewart) returns to the city that gave him fame when, years ago, he killed the notorious criminal called Liberty Valance (the legendary Lee Marvin). He’s there to attend the funeral of his old friend Tom Doniphon (John Wayne), who died in obscurity. Approached by journalists, Stoddard remembers how they met – and, through flashbacks, the narrative reveals what really happened all those years ago in these men’s lives.

John Ford spent a good portion of his early career mythologizing the Old West, in films like “Stagecoach” and “My Darling Clementine,” creating the heroic iconography of a largely fictitious and misleading idea of the American past. In his later work, however, especially after the war, he pivoted to doing precisely the opposite – to demythologizing the west, revealing the ugliness masquerading as heroism that defined America’s vision of itself. He made a few more movies after this one, but “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” is definitively his final statement on this topic, laying bare the lies the country tells itself to perpetuate their ideals – and how history eventually accepts those lies as truth.

It’s one of Ford’s most melancholic movies; far gone are the adventurous shootouts and horse chases, this an old man’s film, a tender look at a fading time when cowboys and their lifestyle had to give way to modernity. An all-around masterpiece and a contender for Ford’s very best ever.