People like to complain about the sameiness of modern movies; but the fact is, there’s a vast supply of really different, really innovative, and above all, really weird movies out there. You just have to be willing to do some digging to find them. We hope this list will get you underway in your search for some delightfully absurd cinema.

1. Help, Help, The Globolinks! (1968)

You’ve got to admit, operas would probably be a bit more mainstream if more of them were about alien invasions. At least, that was probably what Gian Carlo Menotti was thinking when he wrote this one.

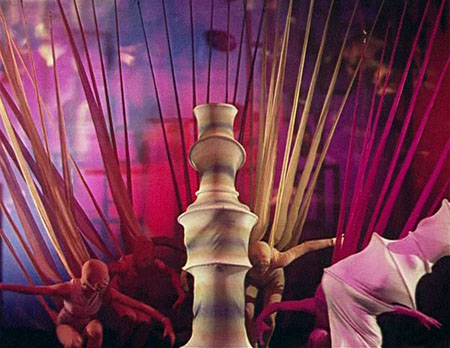

This film is, in brief, the first performance of Menotti’s very bizarre and quirky opera, performed by the Hamburg State Opera and screened on West German television in 1968. The notion of an opera about invading aliens (or “Globolinks”, as they’re called here) is bizarre enough in itself; an opera about invading aliens being defeated by a school band, because they’re apparently allergic to music, is something else entirely. This absurdity is exacerbated by the very creative representations of the aliens, which are depicted either as dancers tied to the ceiling with strange web-like costumes, or as enormous wriggling creatures shaped somewhat like chess pieces).

Combine this with the rather unnatural-sounding lyrics (being a German-language production of an opera originally written in English by an Italian librettist, some things were naturally lost in translation), and the whole thing feels even more like a constructed, unreal world than most melodramatic stage productions.

Really, it might all sound very esoteric, but if you’re even remotely curious about opera, it’ll give you a whole new perspective on the art style, and offer up an experience that’s part film, part stage production, and all profoundly weird.

2. The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea (1976)

Yukio Mishima is an author best remembered nowadays for his very eventful life, which included forming a right-wing nationalist militia and a failed attempt to overthrow the Japanese government. In amidst all this, though, he also wrote some very widely respected novels, including 1963’s The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea.

This particular adaptation – helmed by Lewis John Carlino, best remembered for all those Mechanic movies – moves the action from coastal Japan to coastal England; but otherwise, the story is more or less the same. Single mother Anna begins a torrid love affair with a sailor named Jim, played by Kris Kristofferson. Meanwhile, her son Jonathan falls in with a gang of boys lead by “the Chief”, a sadistic young man who spouts of Nietzschian philosophies about the need to defy adult rules.

It all sounds like a fairly standard, if rather dark, family drama; but the film plays itself out in a deliberately dreamlike manner, with lingering shots of the Devon coastline and the sprawling ocean beyond. There’s a haunting tone recurring throughout the film that makes it feel more akin to a fuzzy, semi-repressed memory than a straight narrative…and it’s one that you’ll be reflecting on a fair while after watching it, uncertain if you’re remembering it right, but knowing that it was a deeply haunting experience indeed.

3. Last and First Men (2017)

Last and First Men is a truly remarkable union of epic scale and minimalist presentation, exemplifying the sort of artistically driven approach that’s now rare even in short independent productions, and almost unheard of in feature length films.

Based on a novel by Olaf Stapledon, the movie tells the tale of how our highly evolved descendants, several thousand million years into the future, flee to Neptune to escape an expanding sun, where, ultimately, the species meets its end. One might expect such a story to be told by way of a glitzy, high-budget, effects-heavy production; but instead, this movie conveys it all through slow, steady, stirring narration (delivered by Tilda Swinton), accompanied by a constantly swelling, haunting score composed by Elazar Glotman.

The visuals, meanwhile, consist entirely of greyscale panning shots of the Spomeniks, a series of World War II monuments erected across the Balkans. With their rugged, Brutalist designs, these monuments, combined with the haunting tale of evolution and devastation we are being told, genuinely come to resemble alien architecture. It’s almost meditative, in a strange way, and perhaps more like an art gallery exhibit than a film; but overall, it’s quite unforgettable.

4. Tuvalu (1999)

Retro stylings may have become trendy in recent years, but films like Tuvalu demonstrate that they’ve always been present to some degree. Following the relatively simple (and perhaps even slightly cliché) story of Anton, a young man fighting to save his father’s ramshackle bath house from demolition while wooing the beautiful Eva, Tuvalu is styled after early 20th century cinema. With its alternately grey and sepia tones, its minimal dialogue (consisting mostly of grunts and single-word exchanges), its sped-up slapstick, and its crumbling, ruinous backdrops, the film evokes a strange meeting point between the artistic beauty of German Expressionism, and the whacky comedy of Chaplin and Keaton.

This heavy focus on retro aesthetic means that the film very much puts style before clarity. Combine this with the often bizarre nature of individual scenes (which include a blind lifeguard overseeing an empty pool and a man and woman playing tug-of-war with an undergarment through broken floorboards), and casual viewers may oftentimes find themselves perplexed at just what on Earth they’re meant to think is going on. However, for the more seasoned cinemagoer, Tuvalu is a wonderful reminder of the fact that contemporary cinema represents but one of the many ways that story can be conveyed on the screen. Cinema has evolved by leaps and bounds over the last century and a bit; and films like Tuvalu play an invaluable role in demonstrating both how far the medium has come, and how modern filmmakers could learn from the old masters.

5. Calamari Union (1985)

Calamari Union is the sort of film that proves that, just because a movie is European, surreal, and heavy with commentary, that hardly means it can’t be a whacky comedy.

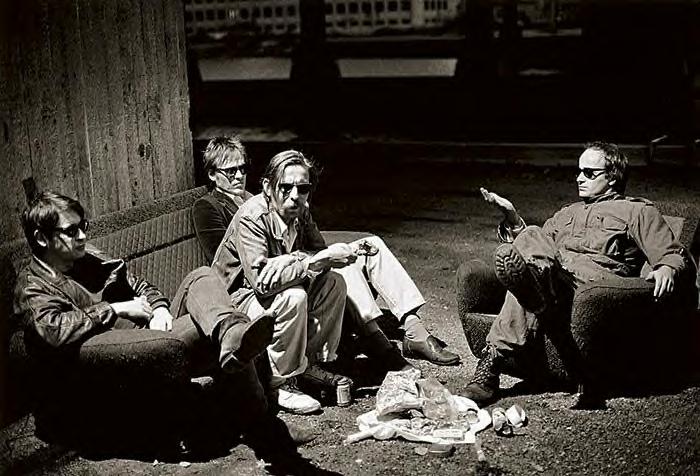

Directed by Aki Kaurismäki – a man not widely known internationally, but a filmmaking superstar in his native Finland – Calamari Union follows fifteen men named Frank, and one named Pekka, as they flee across Helsinki. Their destination is Eira, a seaside neighbourhood that they speak of as if it were a mystical promised land. Along the way, however, they run into multiple hindrances as various members of their group run out of money, become embroiled in crime and romance, and are murdered.

There’s plenty of social commentary that can be read into the film (it is, after all, about a group of men turning their lives upside down for the sake of moving to a more affluent neighbourhood that they perceive as some kind of paradise – the implications about contemporary social mobility are easy enough to discern). However, the film is, first and foremost, concerned with making the audience laugh – partially through genuine comedy, and partially through sheer absurdity.

The film primarily consists of vignettes and non-sequiturs showing the Franks swapping absurd dialogue or getting up to various mischief in their quest for Eira; the narrative is framed in a way that gives it a distorted sense of scale, with the simple act of trekking across a city made to feel like an epic journey by way of the disjointed nature of the scenes and the strange perspective that all the characters seem to have of this simple task. It’s a film that evokes that strange meeting point between confusion and amusement, balancing these elements out and playing them off each other in a way few movies can manage to do.