Ever since the politique des auteurs was adopted by British and American critics from the French magazine, Cahiers du Cinema, directors have been established as the main creative figures in film production. They get the credit for a film’s meaning and for its style, irrespective of the many key contributions from the screenwriter, actors, cinematographer et al. In a sense, they are seen to imbue the work with their own personality and this trace of a personal signature became a new criterion of value in assessing a movie’s worth.

In fact, some French writers went as far as saying that even the lowliest film by a great auteur was worth more than the best film by a journeyman. Odd then that so many films by great directors go unheralded, even when they display so much of the personality for which their makers are celebrated. So, here are ten films that have been totally overshadowed by their more famous cousins, but which share the same DNA, the same family resemblance if you will, and the same hallmarks of genius.

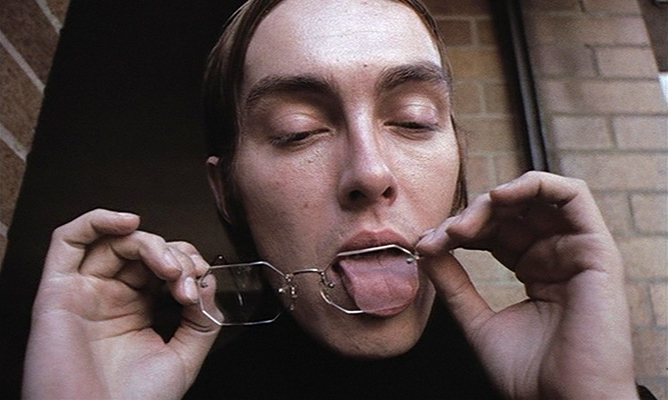

1. Stereo/Crimes of the Future by David Cronenberg

Often the most neglected films in a director’s career are their early works, when they’re getting to grips with the medium and their approach hasn’t fully matured. But these first efforts are also fascinating because they show the new filmmaker in the raw, arguably at their purest, when their ideas have not been compromised by commercial imperatives or audience expectation.

So it is that this strange pair of shorts by Cronenberg, made before his feature debut five years later, are actually his most original and experimental pieces. Which is apt because they both deal with experiments: the first an experiment in telepathy, observing young test cases interacting with each other in an isolated building, the second the aftermath of an experiment which has gone wrong and annihilated the female population. Cronenberg fixates on the psychosexual consequences in each case, following them through with merciless logic to their deliciously subversive conclusions.

2. Young and Innocent by Alfred Hitchcock

Hitchcock, of course, made the key film of his career in his formative years, The 39 Steps (1935), from which the themes and motifs of his later films fractal outwards in ever differing patterns. The first of many remakes and revisions came as early as 1937 in the form of Young and Innocent (1937) in which another dashing young man is falsely accused of murder and goes on the run with a plucky young gal.

The two forgotten leads, Derrick De Marney and Nova Pilbeam, are as spirited and amusing as their colourful names would suggest, and there are enough set pieces to satisfy the most ardent Hitch fan, most notably an incredible tracking shot across a ballroom full of dancers that zeroes in on the face of the drummer, only for his eye to twitch, giving away his true identity…

3. Summertime by David Lean

That David Lean’s Summertime (1955) is neglected is all the more surprising given that it allowed its star, Katharine Hepburn, to play a rare melodrama role, a middle-aged spinster unexpectedly finding love in Venice and was apparently named by Lean as his personal favourite among his films. But it was also a transitional work, as Lean moved away from smaller budgets and British locales to a more epic canvas in more romantic places. And transitional works often confound our sense of what a director does or what they stand for.

There’s none of the literary heft of Lean’s earlier Dickens adaptations, nor the pompous grandstanding of Lawrence and Zhivago. Instead there is Hepburn’s performance, unusually nuanced and naturalistic for a film of this kind, the lush score, and an understated pictorial elegance, most beautifully realised in the farewell wave from the train that ends the picture.

4. Il Grido by Michelangelo Antonioni

Similarly, Antonioni’s Il Grido (1957) marks a turning point in his oeuvre, retaining the linearity and realism of his early work but anticipating the more opaque narrative style he developed in the ’60s. It also stands out among his films because of the way it foregrounds a working class protagonist, a factory worker compelled to drift from village to village, from woman to woman, in search of a connection.

As such, it lays the foundations for the emotional and spiritual restlessness experienced by Monica Vitti in L’Avventura (1960) and Jack Nicholson in The Passenger (1975), but importantly without taking its eyes off the gritty realities of blue collar life poverty, industrial action, and hardship. Antonioni reportedly had problems with his American star, Steve Cochran, but there are a number of great actresses among his screen conquests including Alida Valli and the intriguingly named Dorian Gray.

5. Il Generale Della Rovere by Roberto Rosellini

Antonioni’s great contemporary, Roberto Rosellini, received awards but also an ambivalent critical reception when this film was released in 1959. After two groundbreaking periods in his career – his Neorealist war trilogy and then his celebrated work with Ingrid Bergman he served up a much more conventional narrative feature here, in which Vittorio de Sica plays a con man blackmailed by the Nazis into imitating a partisan leader.

Shot on studio sets with touches of melodrama, it seemed to mark a decline in ambition. But on its own terms, it works beautifully. De Sica proves he was as exceptional an actor as a director, and it’s a great prison movie. Maybe the reason it remains underrated is because it is untypical of its maker, and the personality cult around auteurs means we downgrade anything that doesn’t conform to our conception of their style.