6. Massacre Gun (Yasuharu Hasebe, 1967)

Stripping back the exclusively high brow content for a minute, let’s take a look at this overlooked Yakuza thrill-ride, Massacre Gun. Thankfully brought back to life by Arrow Video a few years ago, Hasebe’s thrilling crime film makes for a real stand-out from the gangster genre, mimicking the best traits of crime cinema from all around the world, from the incredibly smooth and slick film noir that had become huge in America a couple of decades before to the Italian neo-realism that grounded the crime in reality, Massacre Gun is a film of many influences and yet it proudly wears each and every one of those influences on its sleeve, creating a simple but nevertheless engaging Yakuza film that really deserves a lot more recognition for its beautiful, almost orchestral cinematic harmony.

7. Your Face (Tsai Ming-Liang, 2018)

Tsai Ming-Liang has already made his mark on the 2020s with his latest film, Days, which is surprisingly tender considering that it comes from the often quite deranged Tsai, however, those with a keen eye will recognise Your Face as perhaps his most tender film. A talking heads documentary that is largely without talking, the film is simply a collection of close-ups of faces of interviewees, who can choose to talk if they like, sit silently and look into the camera or even sleep peacefully in one case.

With such a gentle approach to the documentary style, intelligently cobbled together from Tsai’s humanist interests as well as his always fascinating approach to slow cinema, Your Face is a striking and memorable film thanks to its complete departure from expectations. It becomes a beautiful and truly meditative (a word that seems to be thrown at too many films lately) piece that takes a little adjusting to but lingers in the memory in a way that few other films do.

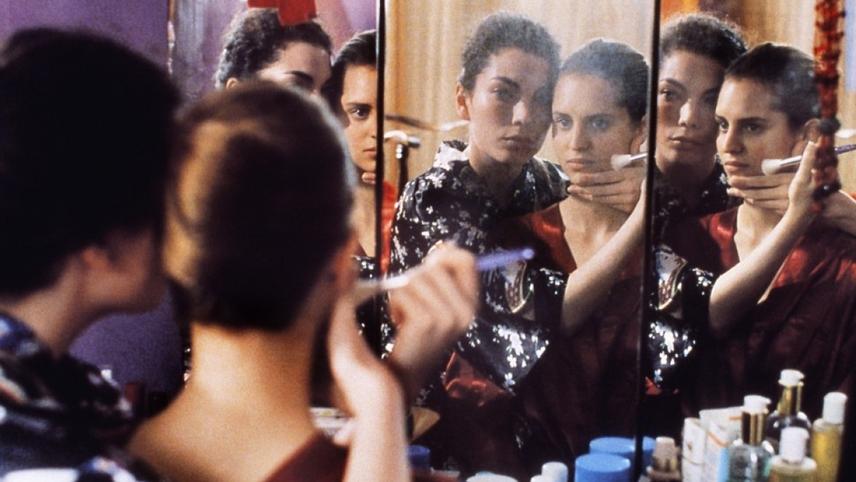

8. Secret Things (Jean-Claude Brisseau, 2002)

Jean-Claude Brisseau’s work seems to be quite overlooked and forgotten generally, but in the case of both Secret Things and The Exterminating Angels especially it can be painful to see just how left behind the two films are considering their quality. Secret Things is a really quite disturbing and menacing film about two women who decide to leave their lower paying jobs and use sex to their advantage in an office setting to manipulate their way to the top leagues, whilst having plenty of erotic fun in the process.

Channelling inspiration from so many different cinematic greats, from Bunuel to Hitchcock just to name a couple, Brisseau creates something quite unlike most any other film and really drives home the ideas about power and manipulation present in sex. It’s a perfect blend of sleazy and incredibly intelligent, meaning that you can essentially watch what is at times really quite pornographic without feeling any real guilt about it, and beyond that simple pleasure, it’s just an incredibly good film with important points to make about sex in the modern world. I’m sure it’s no surprise to find out that such a film is also from France!

9. Melancholia (Lav Diaz, 2008)

Lav Diaz is definitely a director who needs little introduction by now, but for those unfamiliar, his style revolves around extremely long films, slower pacing and long takes focused on Filipino life… and Melancholia might be his crowning cinematic achievement. Clocking in at around eight hours (yep – you’re reading that right – eight hours!) and focusing in on the lives of three characters who try to dispel their angst that comes from living in the Philippines in an… unorthodox way.

Funnily enough, the fact that this film is eight hours makes it no easier to talk about in terms of both plot and form, with both being in a world of their own and the plot especially being hard to really define in any meaningful way without ruining the greatness of the film. Diaz masterfully juggles the narrative with his technical approach to it, managing to make the form act as a key player within the narrative itself that becomes the guideline for much of the important emotion of the story.

The performances are just incredibly lifelike and down to earth, Diaz’s cinematography as always is a brilliant mix of both gorgeous and urban which creates this distinct mood that really makes his films feel all the more real as well as all the more cinematic simultaneously and, as has been said before, the ambition and audacity of this narrative and the way in which the form is used to tell it is simply mind-blowing.

Diaz is an endlessly impressive director, and thankfully one who is starting to get more and more credit overseas as time progresses, but even so, he is in need of much more credit for his major work and importance to the slow cinema movement that is also slowly becoming increasingly recognised by film fans as something exciting and even seeing it as a potential game changer for the general approach to cinematic storytelling.

Melancholia is one hell of a film, and it deserves to be seen by so many people – try not to let the runtime put you off, or start with Diaz’s Norte, The End of History (2013) instead, which clocks in at a more reasonable four hours and is a great introduction to his style.

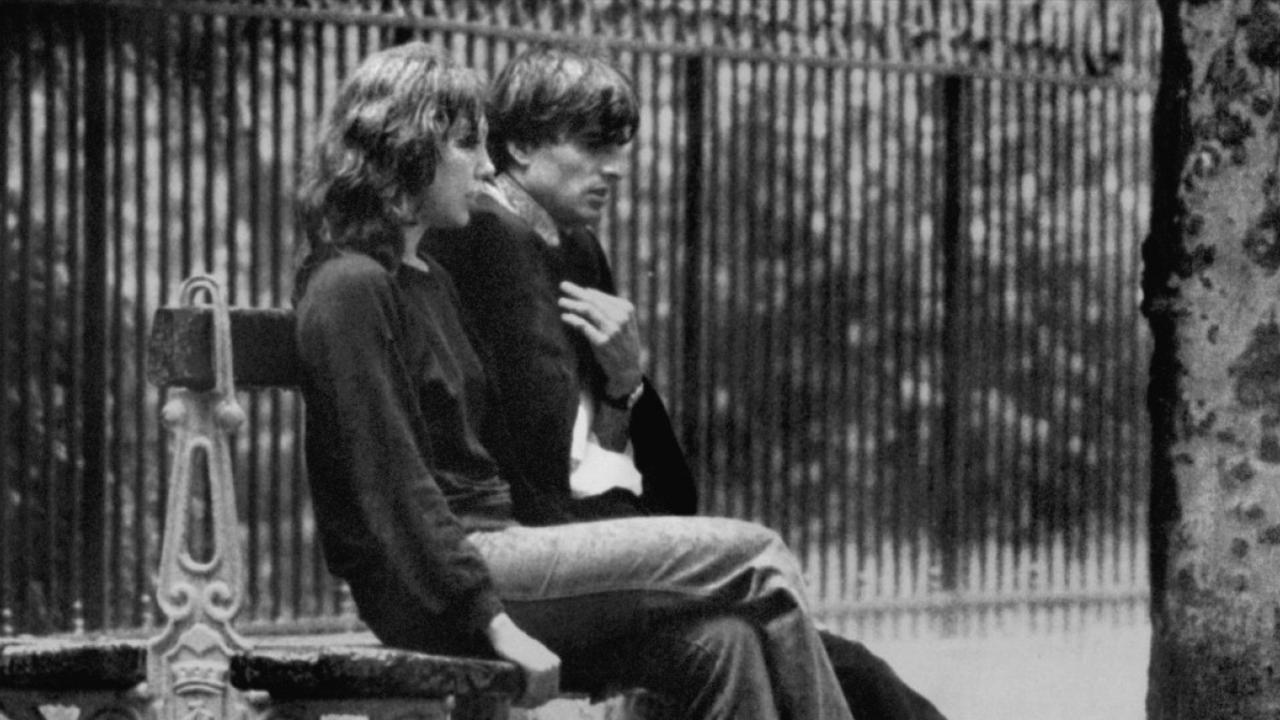

10. L’Enfant Secret (Philippe Garrel, 1979)

One of the first features from the highly regarded French director Philippe Garrel, L’Enfant Secret (The Secret Child), is a semi-autobiographical film looking at Garrel’s reaction to Nico cheating on him with Alain Delon and them having a child together. More than that, however, it is an absolute blinder of a film about the struggles of a couple and the more private effects that actions can have on a family structure as a whole.

Utilising more varied cinematic techniques than most other directors (showing the lasting influence of the French New Wave as well as Garrel’s own style) to help the audience to find the emotions of the characters and then consistently twisting the narrative to also twist those set-up emotions, Garrel has a masterful hold over the way that the narrative moves as well as a strong hold on his almost helpless audience. It’s genuinely quite thrilling to see a director hold such a control and be able to put his audience in such a trance – it doesn’t happen very often, and yet Garrel manages to do it with some consistency.