Science fiction has been a very common genre in human narratives for a long time. In the middle of the 17th century, literary works were recognized that would have certain characteristics of the genre, but it was in the 19th century, with the great books of Mary Shelley, Julio Verne and HG Wells that, influenced by the rapid and significant technological advances of that era, created narratives that blended scientific facts with a prophetic (and often dystopian) view of human reality.

In cinema, it was not long after its appearance in 1895 that science fiction films began to appear; as early as 1902, Georges Meliés’ “A Trip to the Moon” fascinated crowds and showed the great potential that cinematographic art could have in portraying these kinds of stories.

Soon, the studios realized how much these stories fascinated the human imagination even more when told through images, and since then, more and more fictional films have appeared and consolidated the genre. The Star Wars franchise is one of the most successful in history, and many of the most acclaimed filmmakers have surrendered at some point to the genre, such as Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky.

Although any film that follows the conventions of the genre can be considered unusual in that they imagine a different reality from which we live, several filmmakers have managed to use characteristics of science fiction in a very peculiar way.

Whether it be in dealing with psychological, political, and existential issues in an unusual way, or in performing a purely aesthetic manifestation, some have extrapolated to the standards of the genre and have resulted in strange yet powerful films.

10. Alien 2: On Earth (Ciro Ippolito and Biagio Proietti, 1980)

The 1979 classic “Alien,” directed by Ridley Scott, is undoubtedly one of the great sci-fi films in history, considered a true milestone in the genre and acclaimed by the great public. However, not everyone should know “Alien 2: On Earth,” directed by Italian filmmakers Ciro Ippolito and Biagio Proietti.

Released a year after Scott’s classic, the production history of this film is as weird as the film itself; taking advantage of the success of the 1979 film, Italian producers decided to launch this “unofficial sequence.” This practice, however, was not new in Italy, and there are known cases of “false continuations” of various American successes, such as “Jaws,” “The Exorcist” and “Dawn of the Dead,” among others. FOX even attempted to sue Ippolito for using the name “Alien,” but since there was already a 1930 novel by that name, the case ended up being closed.

As its subtitle already shows, the film is set on planet Earth, where its inhabitants eagerly await the return of a spacecraft containing a group of astronauts who had left on a complicated mission. However, the ship arrives on Earth without its occupants, while scientist Thelma Joyce, in the midst of a TV interview, ends up having a catastrophic vision of the future.

Mysterious blue rocks begin to appear on the planet, which we will later know to be something far more dangerous than they seem. Along with her boyfriend Roy and other friends, Thelma embarks on an expedition to a mysterious cave, where they will face the dangers. “Alien 2” is a typical low-budget Italian horror and science fiction film; creative solutions to overcome financial constraints are seen, as well as the extreme use of elements and effects of gore and trash.

9. Je t’aime, Je t’aime (Alain Resnais, 1968)

Alain Resnais is one of the postwar filmmakers who best knew how to use the tools of editing as an establishment of the form, aesthetics, and language of his films. “Last Year at Marienbad” and “Hiroshima, Mon Amour” are the best known and acclaimed, but “Je t’aime, Je t’aime,” the only science fiction made by Resnais, has a relatively common plot that articulated in a bold way.

The protagonist of the film is Claude Ridder, a man who, after a failed suicide attempt, was selected to serve as a guinea pig in a scientific experiment that had only been previously tested on mice: nothing less than a time machine. But something goes wrong in the process and he ends up getting stuck in his stream of memories, and that’s where the film gets really weird; from this point on, the narrative is articulated as if it were the very stream of memories that Ridder is taking in your mind.

As scientists try to bring him back, the editing recreates his hesitation;, there are several scenes that repeat themselves, shots that bump and start over again, and gradually we understand what in fact happened in his life. One of the strongest points of the narrative is his Schroedinger cat-like element: we learn that Catherine, the woman who permeates Ridder’s memories, has died, and the big question about whether or not he killed her leaves the atmosphere even more engaging.

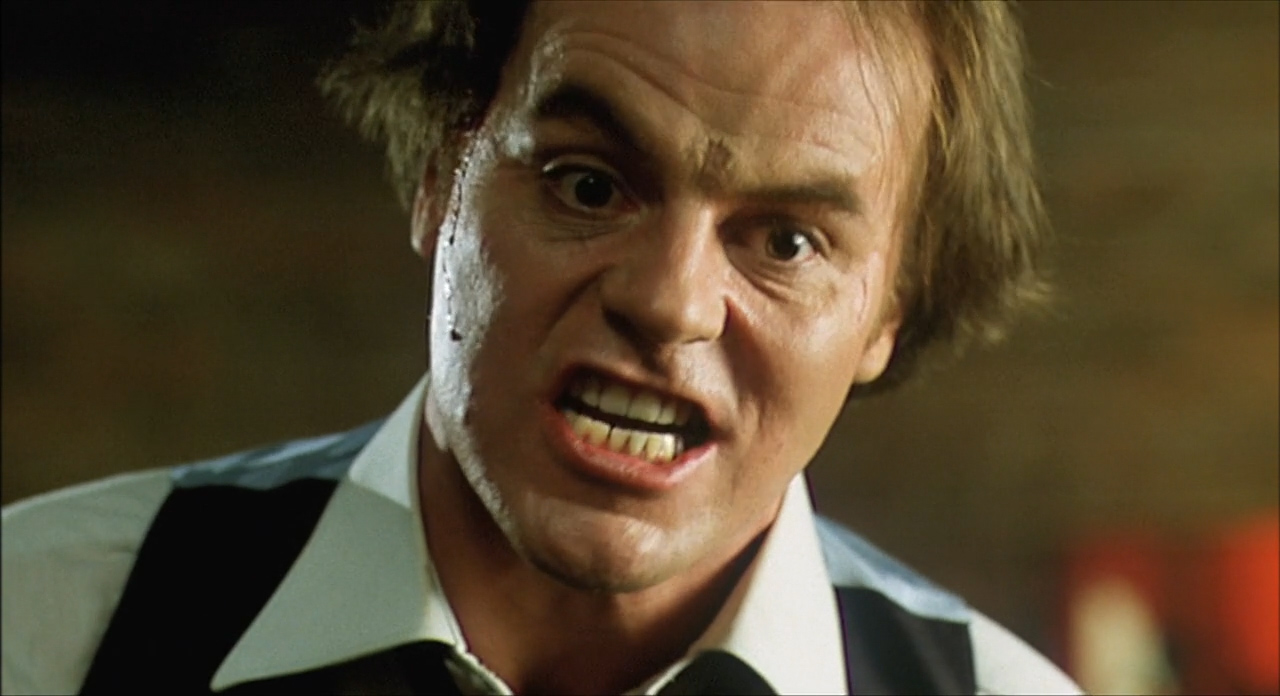

8. Scanners (David Cronenberg, 1981)

Perhaps “a movie that will blow your mind” has never been as good a definition for “Scanner.” David Cronenberg is a true master of making films that, above all, cause a great strangeness and discomfort to his audience (“The Fly,” “Crimes of the Future” and “Naked Lunch” are just some examples) and in this sci-fi with elements of thriller, the Canadian director does not disappoint.

Dr. Paul Ruth is a scientist at the major international security corporation ConSec. He runs secret research on scanners – humans who would have enormous telekinetic abilities – and can even control minds.

The great interest of the corporation in the scanners is the possibility that they can be used as weapons in the international espionage game, but his plans are obstructed after Darryl Revok, the most powerful of the scanners, literally blows the head off of an employee in front of several possible investors, and runs away to start a conspiracy of scanners with the goal of dominating the world.

Faced with these problems, Dr. Paul sees an excellent opportunity when he finds Cameron Veil, a scanner who knew nothing about his situation until then, and will now be used by ConSec in an attempt to contain Darryl’s breakthrough. With typical special effects from the 1980s, following an aesthetic line that explores the grotesque, “Scanners” is certainly a weird and unconventional sci-fi film.

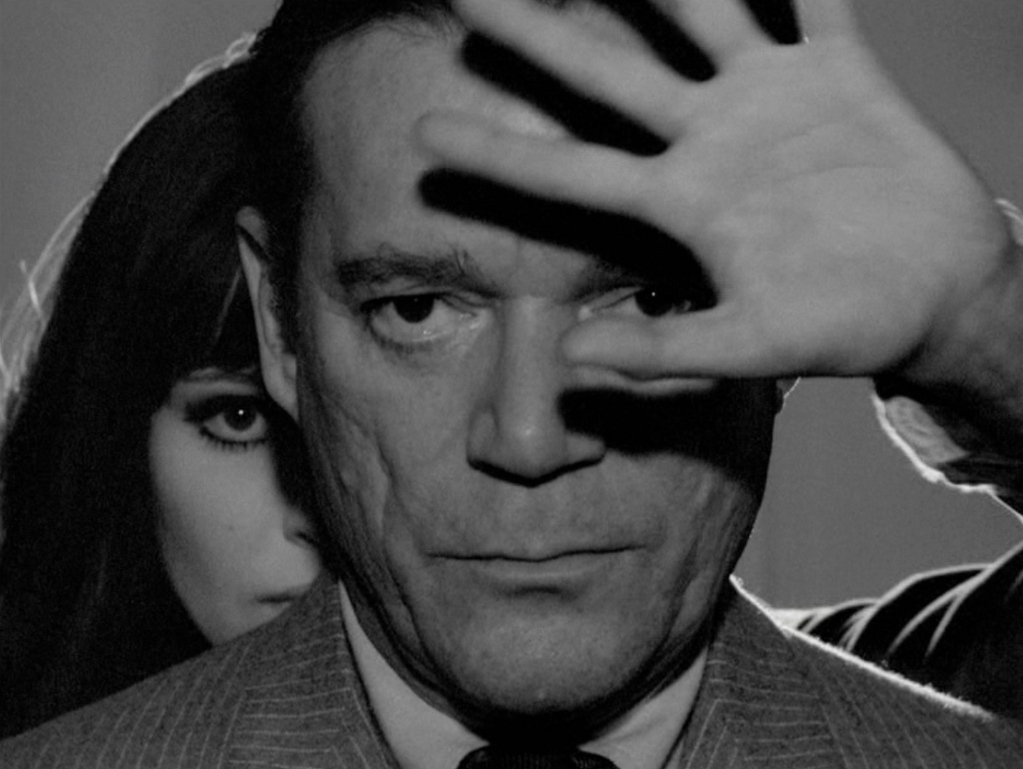

7. Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

In this 1965 film, Godard imagines a dystopian future in which existence is led by technology, in a narrative clearly influenced by the work of Jorge Luis Borges. Such a theme may not seem so innovative or surprising, but it is Godard’s way of dealing with it here that sets it apart from others. Using elements from the classic American noir films, “Alphaville” is a unique science fiction film with a sullen look that casts a beautiful reflection on the fate of humanity in the face of the hegemony of technology over human life.

Alphaville is a futuristic city that prevails over the power of Alpha 60, the computer that commands the inhabitants, having made them lose the capacity to have feelings. The protagonist is Lemmy Caution, a secret agent sent to Alphaville disguised as a journalist with the mission to find the scientist Von Braun, who is responsible for programming Alpha 60.

In the midst of his mission, Lemmy meets Natasha, the daughter of Von Braun who will accompany him and end up falling in love with him. With a dense rhythm and full of philosophical dialogue, we follow the mishaps of Lemmy and Natasha in this strange universe of future-noir created by Godard.

The film calls into question the ideals of progress at all costs and the utopia of a perfect world when permeated by the facilities brought by technology, something so in vogue in the 1960s as today. Something that was important to Gogard and becomes clear in “Alphaville” is his great distrust of an optimism about a more technologically advanced future.

The scene between Lemmy Caution and Alpha 60, which exemplifies some of the movie’s climate, is noteworthy: instead of a conventional confrontation, we have an elegant discussion in which Alpha throws puzzling questions, while Lemmy cites Pascal and uses the power of poetry to overcome the machine that is unable to understand such feelings.

6. Ga, Ga: Glory to the Heroes (Piotr Szulkin, 1986)

Part of a great generation of Polish filmmakers who emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s from the Lodz Film School, Piotr Szulkin became known mainly for his four dystopian science fiction films. This tetralogy is made up of films that hold in common an acidic criticism about the regime of the Iron Curtain to which Poland was subjected, and to a post-industrial society in which the media emerged as a great manipulator of public opinion.

In “Ga, Ga: Glory to the Heroes,” the protagonist is a silent inmate who will be the pioneer of a government program that intends to send its prisoners on somewhat dubious mission to unexplored planets, with the intention of colonizing them. In his departure, he receives the duty of nailing a flag in the soil of the planet and returning in a few days.

However, as soon as he arrives, he is welcomed as a ‘hero’. He is treated as a savior of the motherland, given some perks and moments of fame and praise, but all of this will be done under one condition: he must commit a crime and then be subjected to torture, which will be broadcast on TV as a great spectacle. He is never asked whether or not he accepts, as if it were simply the duty of a hero of a nation to propose a moment of hope to the people, and then be judged and exterminated through a totally spectacular process.

“Ga, Ga” is the Szulkin film with the greatest amount of comic elements and it is impressive how his art direction, despite the low budget, contributes to the creation of the allegory. Designed by Halina Dobrowolska, an important art director who has contributed to several films by Kieslowski, Wajda and Zanussi, she constructs here a universe that is at first gloomy and opaque, but which at the same time makes a satire of Polish society with the insertion of clearly symbolic elements with grotesque, flashy and exaggerated characteristics that seem to disrupt much of their surroundings, revealing the general apathy in which the characters live in such a context.