Film is, traditionally, a medium for storytelling. When watching a film, one usually expects to be able to comprehend the narrative and message of the film (if there is one) on a purely mental level. There are many films, however, that breach far beyond conventional narrative structure or logic.

Some films don’t have a definitive interpretation. Some films work better on a metaphysical level rather than an intellectual level. Some films make sense emotionally, but not logically. This list explores such films that are better felt and experienced rather than fully understood.

1. Eraserhead (1977)

Being one of the first and most important American cult classics, Eraserhead is an unfathomable 1977 debut from the iconic director David Lynch. To call the film surreal is a gross understatement.

The film has no arc or logical narrative in the traditional sense – it instead dwells in the mental hellscape and paternal dread of its anxious and bed-headed protagonist Henry, brilliantly portrayed by John Nance. Eraserhead creates an environment of industrial drones and decay. Phallic creatures hide in the dark. A little woman sings in the radiator. A pimply, wailing frog takes place as Henry’s newborn child. It’s a film that revels in the deconstruction of the human body and sex drive.

Admittedly, Eraserhead is, on paper, little more than a hodgepodge of nonsensical repulsive imagery and body-horror surrealism. But in the hands of such a capable artist like Lynch, the film perfectly captures the angst of adulthood, parenthood, and lust in a crumbling, oppressive urban landscape.

The film doesn’t work on an intellectual level; there’s no use breaking down or analyzing the plot. The dread and vision of Eraserhead is felt in a deep, subliminal sense, and it sticks with the viewer long after the credits roll. Eraserhead is both a landmark in cult cinema and one of the greatest (and strangest) directorial debuts of all time.

2. Angel’s Egg (1985)

Directed by Mamoru Oshii of Ghost in the Shell (1995) fame, Angel’s Egg is an often forgotten but essential masterpiece of abstract cinema and animation.

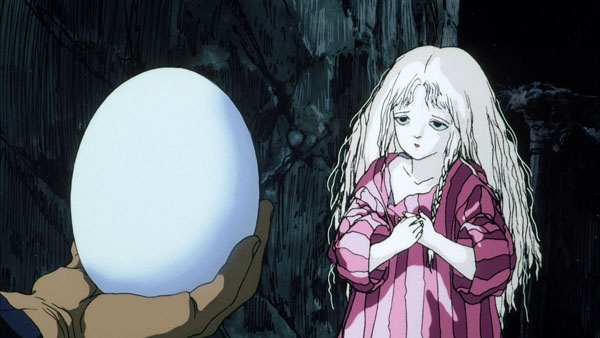

The film follows a mysterious young girl with long, flowing hair as she wanders around a gothic, decaying landscape, cradling a large egg in her arms. The few lines of dialogue in the film are few and far between, shared between the girl and an older boy she meets, who carries a cross-shaped weapon on his back.

Visually, Angel’s Egg is stunning – the hand-drawn animation creates an entirely unique and haunting atmosphere. Like the other films on this list, Angel’s Egg succeeds on an emotional sense rather than an intellectual one. Oshii utilizes biblical imagery and themes in the film to reflect his own betrayal of the Christian faith. In this way, Angel’s Egg is a deeply personal and somber film. There’s a sense of loss throughout the film; the loss of identity, of innocence, of purpose – perhaps feelings Oshii experienced in his rejection of faith.

The film’s two characters wander aimlessly and silently in a beautiful and eerie landscape, seeped in an eternal night. Angel’s Egg reflects the eternal wandering; the eternal search for satisfaction, until the journey has gone on so long one forgets what they were even looking for in the first place. It’s a quietly soul-crushing and gorgeous work of art.

3. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)

Uncle Boonmee is the 2010 international breakthrough from multi-medium Thai artist and director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, more commonly referred to in the West by the name of “Joe.” Based on a 1983 novel by Phra Sripariyattiweti, the film was the first Asian Palme d’Or winner at Cannes since 1997, and the first Thai film to ever receive the honor.

The film’s plot is secondary, and to attempt to understand the film in a linear sense is nearly impossible in one sitting and besides the point. Uncle Boonmee, like most of Weerasethakul’s work, explores the ideas of memory and reincarnation – the ways in which all living things are alive, reborn, and continue to live in a spiritual sense.

Rather than guiding us along a definitive narrative, the film creates a space – a space of overwhelming peace and tranquility, and a space to reflect on our own being in the universe. It’s a pseudo-fantasy world simultaneously steeped in the reverie of Thai folklore and the realities of a tumultuous modern existence. It’s both a deeply personal film and an entirely universal one.

Uncle Boonmee dwells in the limbo between the edge of life and the beginning of death, like witnessing a fading dream. It’s a landmark of contemporary cinema and a necessary viewing for anyone interested in avant-garde narrative cinema.

4. Gozu (2003)

Gozu is not for the faint of heart. Directed by the prolific Japanese cult maverick Takashi Miike, the film makes good fun diving into all of the most taboo psychosexual crevices of the human mind, and then some. It’s a nasty and bizarre film, entirely beyond rationality and comprehension, but brilliant in execution.

Unlike many of the films on this list, Gozu has a more linear approach to plot. That being said, things still get very strange very quickly. The film opens on a member of the yakuza named Ozaki, played by frequent Miike collaborator Show Aikawa.

Ozaki is unhinged mentally, as made clear by his spontaneous murder of a pedestrian chihuahua under suspicion it was a literal enemy threat to the yakuza syndicate. The yakuza boss, viewing Ozaki as a threat, orders his subordinate Minami to get rid of Ozaki – that is, to kill him. Just when Minami thinks he completed the job, however, he finds Ozaki’s body has completely disappeared. Insanity ensues.

Miike relishes in messing with the viewer. The last shot of this film is literally a man laughing maniacally at the camera, breaking the fourth wall and mocking the audience. If Hitchcock enjoys “playing the audience like a piano,” Miike has us on little puppet strings. It may be impossible to connect the dots and create a definitive meaning out of the film, but that’s beside the point.

Gozu doesn’t make sense on an intellectual level – it assaults its audience with an entourage of hysterical discomfort and debauchery. The question isn’t whether or not one objectively understands Gozu, it’s whether or not one is willing to enjoy the sick, twisted ride. In this way, everyone may find their own meaning in Gozu, similar to much of Miike’s other transgressive works.

It’s a subjective experience that forces the viewer to plug their own experiences and subconscious emotions into the film, rather than a film attempting to force its own moral agenda and meaning upon the viewer. Gozu is not a comfortable or comprehensible experience, but it is a necessary one, and one of Miike’s greatest films to date.

5. Taste of Cherry (1977)

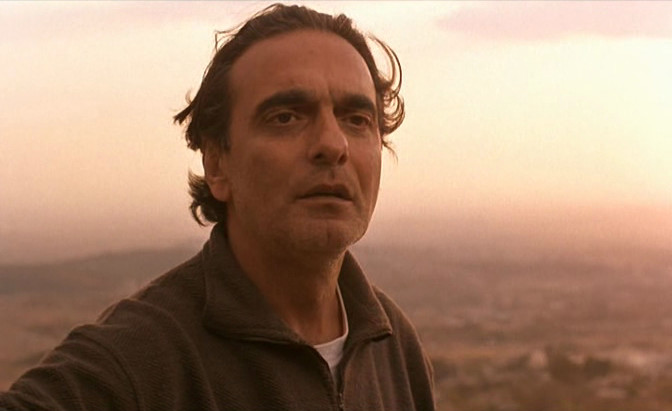

Directed by the prolific Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami, Taste of Cherry is a quiet and simple yet powerful testament to life and finding one’s personal meaning.

The plot of the film, unlike others on this list, is incredibly straightforward. A middle-aged man drives around Tehran looking for someone to complete a job for him, in exchange for a large sum of money. What this job is remains a mystery for the first act; detailing any more of the narrative would detract from the film.

Even though Taste of Cherry is rather easy to comprehend, its simplicity allows room for multiple interpretations. Taste of Cherry succeeds because it is not an objective or mental exercise, but an emotional one. It’s not a film that should be understood on mere intellectual terms, but rather a film that allows meditation, processing, and reflection.

Taste of Cherry even breaks the fourth wall and reminds its audience that what they are watching is nothing more than a film, further presenting its central question: why do you wake up every morning? It’s not a film with answers, but a film that opens room for discussion around an age-old dilemma.