There comes a point in the third act of a film where something can change our entire perception. Sometimes the film derails and gets ridiculous, has a crazy plot twist, or simply surprises us in ways we didn’t expect.

Most importantly, we remember these third acts more than the rest of the film. Not that everything leading up to it is disposable, but the creative decisions behind the climax linger in our heads long after the credits are finished. Due to the nature of this list, spoilers alert ahead.

1. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) – Steven Spielberg

Yes, even Spielberg can’t always follow his uplifting endings, usually accompanied by John Williams and visual splendor. This is the one film in which Spielberg had wished he’d changed the ending. Everything leading up to the climax of the film is superb, but it’s the main decision of the protagonist that makes us ponder, like himself at the aliens.

The score, Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography, the spiraling descent of Richard Dreyfuss’ obsession, and of course, François Truffaut. Toward the end of the film, the aliens have finally arrived on Earth inside the secret compound by the United States government on Devil’s Tower. What follows is a stunning frame where we hold our breath and wonder what’s going to happen as the chants, rhythm, and sounds feel like we there as well. But when Dreyfuss’s Roy Neary gets on the UFO and essentially abandons his family, it can be a slight oversight.

This is what Spielberg regretted, because despite an uplifting and peaceful encounter of what could have been impending doom, we watch the father leave his family for his own selfish curiosity and wonderment. It doesn’t take away from the rest of the film, but it makes you question the protagonist’s true senses and wonder if he would have been better off alone.

2. Moonrise (1947) – Frank Borzage

A film that was sadly overshadowed during the height of the film noir era, much like the director, Borzage himself in the Hollywood era. The film plays out in film noir style, but with sensitive performances and a deeper meaning of love and understanding.

That’s the key to unlocking most of Borzage’s filmography and it is no different here. As we witness Dane Clark’s Danny desperate flee to escape law enforcement with the help of his murdered victim’s finance, Gail Russell, we see the true meaning of the film. In the third act after running around, Danny comes to his sense of understanding of love, morality, and ethics. Where most films at the time would have opted for a shootout or a gun crazy adventure, Danny simply talks to himself and the nearest cop and turns himself in.

In the final frames of the film, the actual whiteness increases as Danny’s sense of consciousness is awakened and is free from his past sins. This can either be a complete transcendental turnoff or pure cinematic enlightenment for a viewer. The choice is completely up to you as the third act is softer than the rest, but that’s what Borzage was trying to do: tell a film noir story with the sensibility of love and understanding.

3. Oldboy (2003) – Park Chan-wook

A film of Greek tragedy proportions soaking in originality, B-movie gore, neo-noir, and cinematic prowess, Park Chan-wook’s film put South Korea on the map for more exciting endeavors. In this case, we finally get the encounters we want in the third act of the film, but it doesn’t come without plot twists grounded in the characters’ choices.

As Choi Min-sik’s Oh Dae-su tries numerous dumplings and hammers his way through the criminal underworld, he finally meets the man responsible for his imprisonment. No surprise, its contains graphic scenes and dripping blood that we could only have expected and thoroughly enjoyed. But when we flash back to the reason why Oh Dae-su was imprisoned, it takes a traumatic turn.

After the incestuous relationship is revealed for our antagonist, one is revealed for our protagonist in which he weeps and cuts his own tongue out. It completely invalidates all the actions and consequences leading up to this point. Our emotions and reactions begin to play against one another as well. It leads to an epilogue that makes us wonder what actually occurred in the third act of the film, or where our characters went after that. Regardless, Park managed to give into our expectations while flipping the consequences of them, truly showing visual storytelling in his masterpiece.

4. Ismael’s Ghosts (2017) – Arnaud Desplechin

Desplechin’s filmography consists of films that go deeper into their subtext themes, derail for secondary stories, and truly take on a life of their own, much like life itself. Therefore, with his muse Mathieu Amalric, the last 20 minutes of this film go off the rails where the protagonist disappears from the narrative for large segments, but develops into a true French story with magical results.

As the film plays out with Amalric’s long missing and presumed dead wife, played by Marion Cotillard, and his new lover, Charlotte Gainsbourg intersect in his life, the true star of the film, Desplechin, takes full stage. The film weaves in and out of a secondary story that was introduced in the beginning; Amalric pops in and out of what is going on, and the feeling of the film can create a confusion. But if you give into the film, you can come away with a unique feeling that is undeniably French and most importantly, true to the aesthetic of the director and the filmmaking process itself.

Without previous knowledge of the director’s film and style, this may not be the film for them. And in the utmost terms, the third act would prove to be very frustrating and alienating instead of enthralling and exciting.

5. Jigoku (1960) – Nobuo Nakagawa

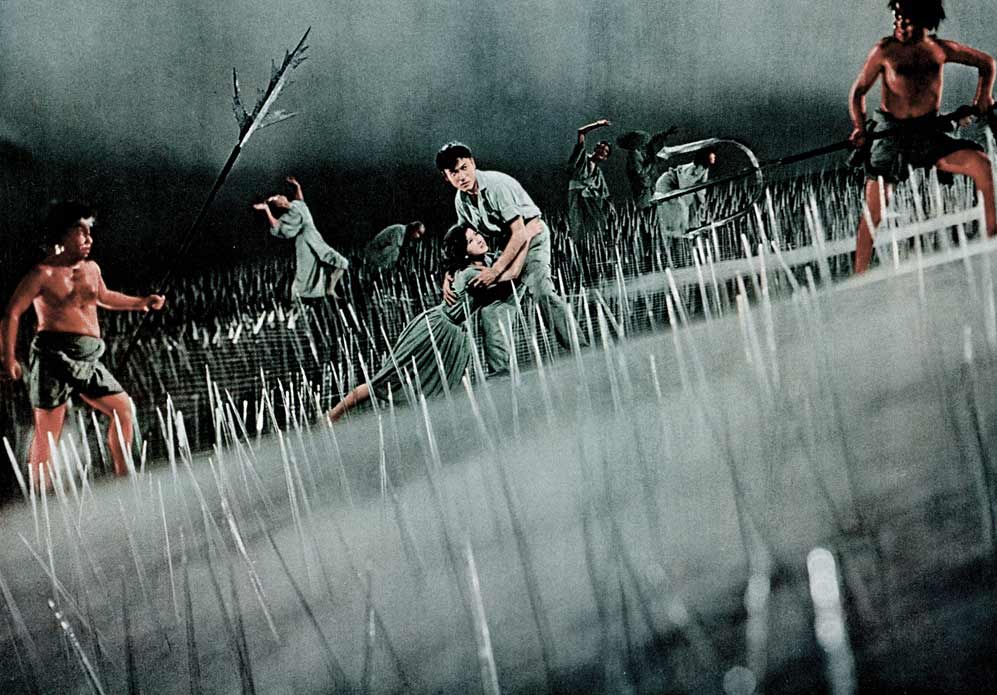

A film that translates to ‘Hell’ or ‘The Sinners of Hell’ by one of the masters of Japanese horror, Nakagawa. In the third act of the film, which is clearly the most memorable, we see our guilt-ridden student literally go into the depths of hell for a visual, horrific, and mind-bending experience.

The film’s core feeling is one of guilt and most of the negative demons like thoughts that plague one’s mind. As the film continues and as Shiro gets more and more agonized over his actions, it somehow makes sense to go to hell in this horror film. However, we are not treated to a typical kwaidan ghost story of Japanese horror folklore, but rather an all-out assault on our senses beyond what we could have imagined. It still holds up for non-CGI imagery and practical effects, because the emotional context is there and is still grounded in the realism of our character and the Japanese film world.

Nakagawa made a string of horror films, but never more here, as he literally went into hell, which serves as a primary inspiration and a status for the depiction of hell. And most importantly, when the film ends, we remember that third act more than anything.