5. The end of Diane Selwyn in Mulholland Drive

What was initially an unaired TV pilot, “Mulholland Drive” is Lynch’s most nuanced and ambitious work when it comes to represent the ambiguous and fractured nature of its characters psyches.

Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts) is a failed actress who works as a waitress in Hollywood, while her ex-girlfriend Camilla (Laura Harring), having already moved on from their relationship, is enjoying a successful and comfortable life as a movie star.

Through the film, it’s suggested that Diane’s jealousy and frustration make her imagine herself as Betty, an alter ego who is able to achieve everything that has been supposedly denied to her in real life, including a successful film career and the love of Camilla. However, unable to cope with her unrequited love and lack of success, Diane hires a hit man to end the life of her ex-partner. The film ends with a guilt-ridden Diane committing suicide in her room.

Diane’s last moments are both terrifying and heartbreaking to witness. After finding a blue key in her apartment, meaning Camilla is dead, Diane begins to suffer hallucinations in which she is tormented by the elderly couple from the beginning of the film. The lights flicker violently as Diane’s ear-piercing screams fill the shrinking space around her. Desperate and inconsolable, she takes a gun from her bedside table and turns it against herself.

Her suicide feels even more meaningful and tragic because of the way Betty is portrayed through all of the film. Diane doesn’t let any of her flaws remain in her alter ego. While she clearly has possessive and sexually dominant tendencies, Betty is naive, innocent and kind. This way, Diane is not only showing contempt for Camilla and the world that surrounds both of them, but also for herself and the way she behaves.

The film is not just a perfect summary of some of Lynch’s main themes such as identity, dreamlike imagery, and criminal backgrounds, but also one of the most emotional, intense, and all-around beautiful films in the director’s oeuvre.

4. Laura Dern walks towards the camera in Inland Empire

The tenth and last film in Lynch’s career is also arguably the least accessible of his works. Shot entirely on digital video and stretching for almost three hours, “Inland Empire” is a garish, confusing and uncomfortable experience from beginning to end.

The film shares many details with the director’s own “Mulholland Drive.” Both films are articulated around an identity crisis of their protagonists, as reality and dreamscape are intertwined to the point that it is difficult to discern one from the other, and in both of them, Hollywood and the film industry in general are represented as a machine that chews and feeds on the dreams and hopes of those not careful enough.

Although the film is incredibly tense during all of its footage, its scariest moment comes in what seems to be a completely innocuous sequence. We see the character of Susan (Laura Dern), who’s only lit by a flashlight in front of the camera, walking towards the screen in slow motion. As she gets closer to the viewer her smile slowly turns into a grimace, culminating in a sped-up close-up where we see her face distorted because of the the wide-angle lens of the camera.

The scene is so nightmarish thanks to the combination of the height and the focused nature of the light source, which is totally unnatural to the eye of the viewer, as well as for the change in speed and startling sound cue that accompanies Susan’s grin.

Although Lynch has expressed his disinterest in returning to the big screen, “Inland Empire” is a more than successful farewell that, at least for now, closes his film career on a obscure and gripping note.

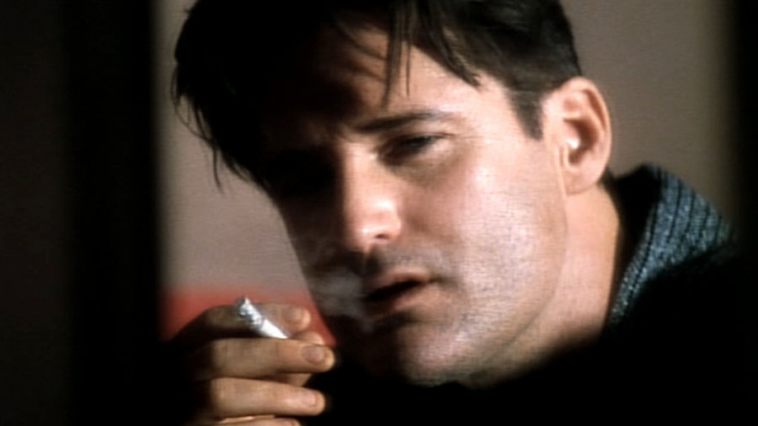

3. Fred watches the tape alone in Lost Highway

The disruption that an unknown presence is inflicting in Fred’s life in “Lost Highway” is represented both in a metaphorical and in a literal sense: first with the creepy tapes that Fred and his wife Renee receive anonymously at their home, and then through the supposed affair of the latter with one of their friends.

Both threads collide when Fred decides to play the last tape sent to the couple all by himself. Even though its footage seems to be fairly similar to the one found in the previous one, this time, instead of watching the couple asleep in their bed, the tape ends with a bloody and desperate Fred surrounded by the torn apart body of his wife.

Lynch plays again with the ambient noise, adding some little cues in order to emphasize the beats from the scene. However, it is the height and smoothness with which the camera moves that makes the scene so sinister. Its point of view makes it clear that no real person could have recorded the footage by any conventional methods, suggesting the presence of something both menacing and ethereal. The grotesque ending is made even more unsettling when Fred himself acknowledges the camera upon him without giving away its operator.

Although many of its motifs would be later explored in “Mulholland Drive,” “Lost Highway” still remains Lynch’s most stylized film and one of the director’s most well-known works.

2. Behind Winkie’s Diner from Mulholland Drive

Among all the sequences from Lynch’s filmography, the one that takes place at Winkie’s Diner in “Mulholland Drive” is both his most unexpected, ominous, and the one that best reflects the ambiguity and eeriness that we commonly associate with the realm of the dreams and nightmares.

The setup is fairly simple: two men are having breakfast at the diner when one of them tells the other about the recurrent nightmare he’s been having about a monstrous man who is standing in a nearby alley. In order to get rid of his uneasiness, both decide to check out the place so the man can finally get over his fears at night.

Although we have been told how the whole scene is going to develop, we’re still expecting nothing to show up behind the restaurant. Its lightning doesn’t suggest that we are in any sort of dreamscape, and visually everything around the men seems to be pretty normal and unremarkable. And then the monster appears.

The whole sequence is amazingly acted and is filled with awesome little filmmaking details, like the way it suggests that the second man is reenacting his friend’s nightmare for a brief moment while he’s taking care of the bill; the sound of the cars that becomes an unidentifiable noise that gradually increases in intensity as both men move toward the corner; and, the best of them all, the way every sound in the scene gets deafened at the end after the monster vanishes, mirroring the man who’s collapsed in his friend’s arms.

The scene has become a classic in the director’s filmography, leaving the viewer scared and confused but also deeply staked in the mysteries concealed inside “Mulholland Drive.”

1. All of Fire Walk with Me

David Lynch may have a lot of horror-like sequences in his filmography, but “Fire Walk with Me” is probably the only one of his works that can be considered like a proper horror film by itself, from sexual abuse and murder to straight up evil possessions.

If “Blue Velvet” was about the unknown terrors that you may find in your own neighborhood, “Fire Walk with Me” has them disguised as the people you are supposed to trust the most. Those who watched the TV series know what’s coming: Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) will be brutally murdered by her father Leland (Ray Wise) before the end of the film.

Anticipation is something that is not usually taking into account when it comes to depict the troubled and sometimes horrifying nature of dreams. Memories, desires and expectations get tangled with our deepest fears and “Fire Walk with Me” is possibly the darkest materialization of those in the whole Lynch’s ouvre.

The film is exhaustingly distressing, especially thanks to Wise’s terrifying portrayal of Leland and his erratic, menacing behaviour. There’s a lot of sequences that depict sexual assault, substance abuse, domestic violence and murder but they are perfectly handled thanks to Lynch’s ability and respect when it comes to capture his characters’s emotions through captivating and iconic visuals and sound design.

However, everything else pales in comparison to the last sequence of the film. Laura’s murder is at the same time intense and brutal, but also heartbreakingly tragic for both her and Leland, who begs unsuccessfully for his daughter’s life. We only see fractured images of the event, heightened by the flickering lights accompanied by the choral music in the background, and then the aftermath.

Talking about the music, in the great Red Letter Media’s review / discussion of the film – that also covers some of the points discussed above in much more detail – it is said that Laura may be sacrificing herself in order to protect the people around her and this theory certainly is reinforced by the film itself given the inclusion of Luigi Cherubini’s Requiem in C minor segment Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God”) which plays both during her murder and also in the final credits.

However, there’s a certain ambiguity in Laura’s tears of happiness in the end, especially with its Christological implications taken into account. She is finally free but the violence and abuse can not be erased, something that can still be felt in the much lighter TV series.

Even if it is debatable if “Fire Walk with Me” is (along Mulholland Drive) the director’s darkest film, it is certainly one of his most interesting works given its subject matter and the open presence of supernatural elements. A horrifying and grueling but towering work that only gets better with time.