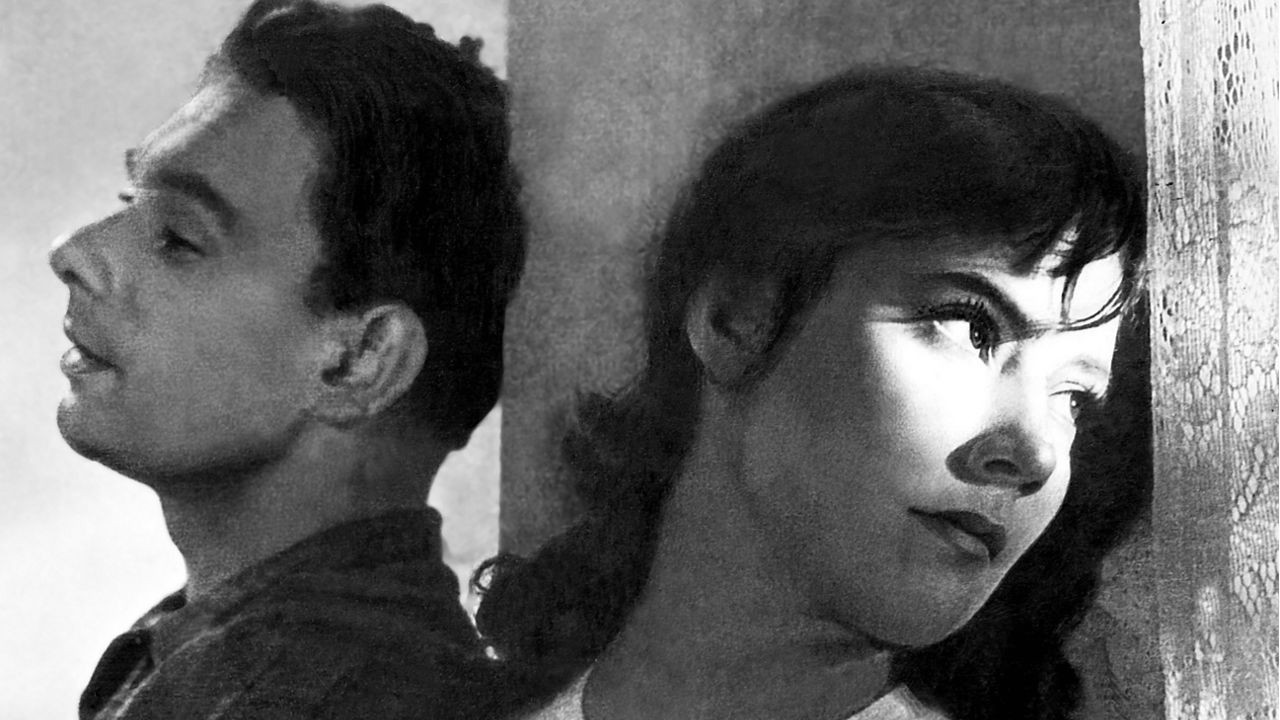

Romantic love is one of the most tumultuous of emotions, ranging from elation to heartbreak in mere moments. It’s something nearly all people experience, making sad romantic films one of the most popular of film genres. Whether it’s the forces of society, illness, being married to the wrong person or simply unable to deal with one another, watching people made for each other unable to truly live happily ever after quickly leaves viewers reaching for their handkerchiefs.

There is meaning in these films beyond mere despondency. They can act as warnings, a reminder to cherish true romance in one’s life and not let it pass you by. And for those who have lost, the effect of watching can be both cathartic and comforting. From Hollywood tearjerkers to some of the most renowned arthouse films of all time, this list shows that sad romance spans both conventional and auteur-driven cinema.

Spanning from 40s Britain to the Soviet Union, Hong Kong to the mountains of Wyoming, our picks show that heartbreak is a universal emotion and can happen to anyone, anywhere. Read on below to find out what we picked as the saddest romantic movies of all time, and the reasons why we picked them. It goes without saying that spoilers will follow.

10. The Notebook (Nick Cassavetes, 2004)

You can’t discuss the saddest romances of all time without mentioning at least one Nicholas Sparks’ adaptation. The American novelist specialises in romantic pairings that are seemingly doomed from the start.

The Notebook was Sparks’ first published novel with the adaptation making stars of its two leads, heartthrobs Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams. They play Noah and Allie, a young couple in 1940s USA who fall deeply in love with one another under the distrustful eye of Allie’s rich parents, who disapprove of her being with someone so poor.

The Notebook has been unfairly maligned as cheesy nonsense, but the direction by Nick Cassavetes, son of the legendary indie director John Cassavetes, is surprisingly robust, imbuing a simple story with genuine heart. It helps that the dialogue – full of memorable lines such as “what do you want!” – is so strongly delivered, especially by Ryan Gosling who was actually cast against type for this film.

It pulls on the heartstrings thanks to its unique framing device, and the reveal that the woman with dementia in the beginning is Allie and the man reading the story to her is Noah. It’s the rarest of things: an ostensible ‘happy’ ending that is nonetheless deeply sad.

9. The Cranes Are Flying (Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957)

The crowning achievement of Soviet cinema and one of the finest anti-war films ever made, The Cranes are Flying is a devastating experience. Telling the love story between Boris, who joins the Soviet army in a fit of patriotism, and his girlfriend Veronika, it finely details the way the war split lovers apart. It was one of the first Soviet Films to really deal with the negative effects of the Second World War, and changed how women were portrayed on screen.

In a cruel twist of fate Boris is killed in battle. Veronika doesn’t know, and is forced to marry another man, thus making her family believe she has betrayed her lover. The emotional effect of these decisions is heightened by the handheld camerawork, which was deeply innovative for the time.

While shaky cam is now mostly associated with action films, cinematographer Sergey Urusevsky used it to get into the subjective emotion of his characters. Here the camerawork creates a breathless effect, allowing us to feel exactly like Veronika does. This is bolstered by a mesmerising central performance by Tatiana Samoilova in only her second ever role. Simply put, it’s a masterpiece, with acres of empathy for all women who lost men during that war.

8. Dr Zhivago (David Lean, 1965)

Based on the Boris Pasternak novel of the same name, which was banned in the Soviet Union due to its anti-communist message, Dr Zhivago is a sweeping love epic for the ages. Spanning over three hours, it takes place against the backdrop of the pre-WW1 years, the Great War itself and the October revolution.

Our hero is Lara – introduced by her own memorable theme composed for the film by Maurice Jarre – played with remarkable composure by Julie Christie. Her fate endlessly interweaves with Zhivago, despite the both of them being married to another, as the both of them are swept up by the tides of history.

It’s a patient film, slowly building up until it reaches a heartbreaking conclusion. David Lean was no stranger to the epic, having just directed Lawrence of Arabia previously. Here he uses every inch of the frame to help give this love affair an extraordinary depth, photographing snow, steppes and city life with great care. Its unafraid to show the bleakest parts of the Stalinist regime, criticising a brutal administration that meant that good people couldn’t be happy together.

7. Love Story (Arthur Hiller, 1970)

The Notebook of its time, Arthur Hiller’s Love Story is a tale as old as time. Boy meets girl. They fall in love. Girl gets terminally ill. Unashamedly melodramatic, its reputation as merely a “weepie” is unfair considering that amount of life that is found in the film hitherto to its tragic latter half.

Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal play the two lovers, Oliver and Jenny, who meet at Harvard. As is common in these stories, he is the heir of a rich family while she is a working-class classical music student. Their dialogue rings true as the two of them bicker endlessly before finally overcoming their socioeconomic differences.

Love is seen as more important than financial wealth, as Oliver forsakes his father’s support to move in with Jenny. But as they plan for a family, Oliver finds out that Jenny is dying of a terminal illness.

While on paper it sounds mawkish and manipulative, the strong direction by Hiller as well as the great acting by MacGraw and O’Neal elevates Love Story into a truly timeless tale. It also features one of the most quotable aphorisms from cinema, “Love means never having to say you’re sorry”, spoken by Oliver after his father apologises for Jenny’s death.

6. The English Patient (Anthony Minghella, 1996)

Based on the novel by the same name by Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient was a massive critical sensation when it came out, receiving 12 Oscar nominations, winning nine, including Best Picture. This achievement was deserved considering how irresistibly romantic The English Patient is. Ralph Fiennes plays Count Laszlo, a cartographer and pilot who falls in love with traveller Katherine Clifton, played by Kristin Scott Thomas, in the Sahara desert in the 1930s.

Interweaving this love affair with the story of Hana, played by an Oscar-winning Juliette Binoche, The English Patient uses its generous runtime to really immerse the viewer into its character’s lives.

The editing is remarkable, going between flashbacks and multiple time frames with ease, leading to a conclusion, devastating because it seemed all so preventable. Yet another love story told against the backdrop of World War II, it gathers its romantic power through the strength of its performances and the epic, Lean-eque cinematography.