Starting in the art world of Paris in the 1920s by artists and poets such as Andre Breton, Guillaume Apollinaire and Louis Aragon, surrealism was adopting as a way of allowing the unconscious to freely express itself. Inspired by the dream theories of Sigmund Freud, surrealism foregoes rational explanation in favour of strange juxtapositions, illogical developments and non sequitur – using surprise as a means to create a new reality.

Its most famous proponents were painters such as Salvador Dali and René Magritte, whose witty and unusual images sought to change the very way one views the world. This influence spread to cinema in the late 20s and 30s, often adopted by arthouse directors who wanted to find new ways to express how things could be viewed and to shake up the status quo.

Whether it’s merely to replicate the experience of dissociation, to shock the viewer to a new political reality or to provide elevated sensory sensations, surrealism is a brave, avant-garde mode of filmmaking that can be a highly rewarding experience.

In many ways cinema is the perfect art-form to express themes of the surreal, as it relies on the suspension of our disbelief. Surrealism is primarily an auteurist means of expression, a highly personal way of ordering reality in one’s own vision, directors seemingly giving the viewer full access to their own unconscious.

The choices that we have picked here reflect the amazing diversity of surrealism, spanning all the way from 30s Paris to 60s Prague to 70s Yugoslavia. Read on below to see which films we picked. Don’t like our choices? Sound off in the comments below.

10. Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, 1929)

No overview of this genre is complete without mentioning Luis Buñuel, who created a vast body of cinema over 50 years that is easily the finest of all surrealist canons. His first film, Un Chien Andalou, was created in Paris with the famous painter Salvador Dalí.

Lasting only 17 minutes long, its dream-logic visions birthed an entire new way of looking at cinema. It features the iconic image of an eye being cut by a razor, with gel streaming out of the eye, a bizarre image the kind of which was not seen in cinema before.

The entire point was to create a film where there would be no rational explanation for the images that appear on the screen, but instead follows the logic of a dream. It wasn’t supposed to make sense, but to shake up the conventional bourgeoisie expectations of cinema. You may not find meaning there – but if you’re willing to open yourself up to it, prepare to have your understanding of cinema expanded.

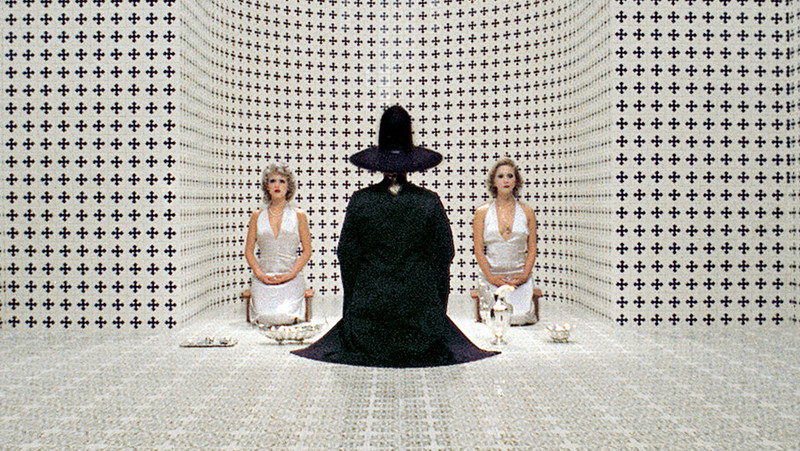

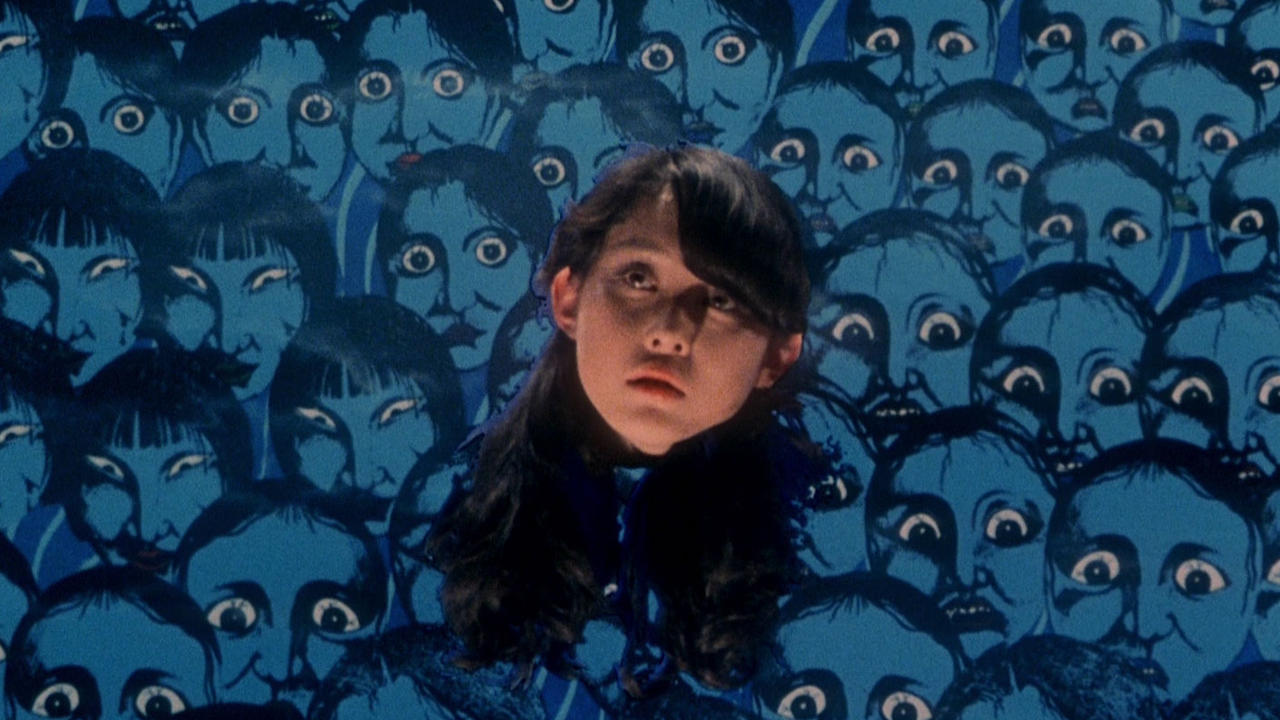

9. House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

A horror film unlike any other, House has to be seen to be properly believed. Taking the cheeriest approach one can find to a ghost killing a group of young schoolgirls, House is the true definition of the phrase “one-of-a-kind.” Moving along at a frenetic pace, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House is a baffling yet deeply enjoyable experience. Surrealism has rarely ever been this fun.

Featuring a piano that eats people, multiple animated breakaways, black and white flashbacks, collage effects, and a cat with the power of omniscience, House sees Obayashi employ the entire kitchen sink in service of creating the most batshit crazy films ever made. And somehow it just works: this is a true cult classic midnight movie.

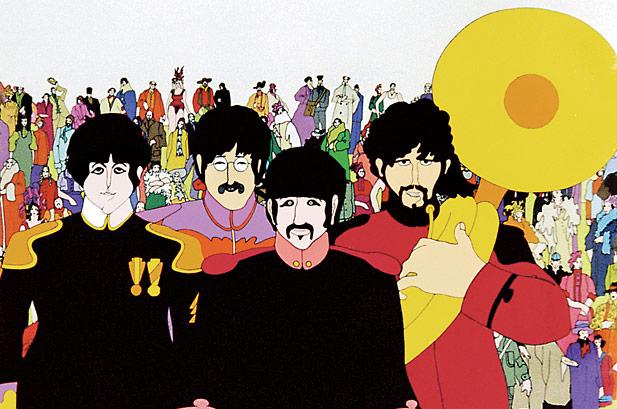

8. Yellow Submarine (George Dunning, 1968)

While perhaps not the best Beatles film – A Hard Day’s Night takes that honour – Yellow Submarine is the perfect trippy exploration of the hippie generation. Seemingly inspired by the sensation of taking LSD itself, its visuals mark a landmark in film animation.

Set in the magic world of Pepperland, it tells the story of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, who are attacked by the Blue Meanies. The band escape and use the Yellow Submarine to find the Beatles and ask them for help.

Making full use of the visual possibilities of animation, the world is comprised of paradoxical landscapes such as the Sea of Holes, and even contains nods to classic surrealist motifs such as Magritte’s big green apple. Aided by a soundtrack by The Beatles themselves – featuring classics such as “Lucy in The Sky With Diamonds” and “All You Need Is Love” – Yellow Submarine is one of those rare films that unites children and adults alike.

7. Weekend (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967)

Using the chaos that occurs on a trip out of Paris as a state of the nation address, Jean-Luc Godard’s endlessly inventive Weekend is easily one of his best movies. Here he embraces surrealism completely yet still finds a way to bend it to his own ends.

Self-reflexive and anarchic to a point of total saturation, it is an assault on the senses that doesn’t really let up until the final scene. It is most famous for a single tracking shot of a traffic jam that goes on for three-quarters of a mile, taking in a whole panorama of French society.

Abandoning their car, the protagonists set off cross-country where they meet historical characters, end up in other people’s movies and see endless, bloody violence. Occasionally characters will break the fourth wall and recite political points directly to the camera itself – making Godard’s didactic approach thrillingly explicit. While his other films may be bogged down too much one way or the other towards politics or a complete abandonment of cinematic norms, Weekend strikes the perfect balance.

6. Daisies (Věra Chytilová, 1966)

One of many anti-authoritarian films on our list, Daisies is a landmark of feminist cinema and one of the most important films in the Czech New Wave. It’s a madcap exploration of two girls that is completely dadaist in its approach, a formally radical film that gleefully rips up the rulebook.

Its two protagonists are Marie I and Marie II, two young girls who have no interest in obeying the patriarchy, and spent the seventy-minute runtime taking advantage of older men. In an iconic scene, the two girls literally cut up phallic objects, such as bananas, with scissors, making its central theme highly explicit.

With a radical approach to juxtaposition, editing, sound-design and colour-filters, Daisies borders on incoherence – but this formal inventiveness and willingness to go against the conventions of cinema is the perfect metaphor for these girls refusal to play according to the rules of men. Like W.R: Mysteries of the Organism, it was banned in Czechoslovakia and director Chytilová was forbidden to work at home until 1975.