Film is a unique art form that is able to reveal what lies beyond what is seen in ordinary life. It is able to convey unique perspectives on life and rather than give answers, it makes the viewer ask questions. Sometimes films focus on bright side of life, others on the fatality of it, and other in its absurdity.

The variety of films that deal with life itself reveals a richness of perspectives that can only by conveyed with film language. Here is a list of 10 films whose subject is life itself – these are films that make us experience a unique glance of life.

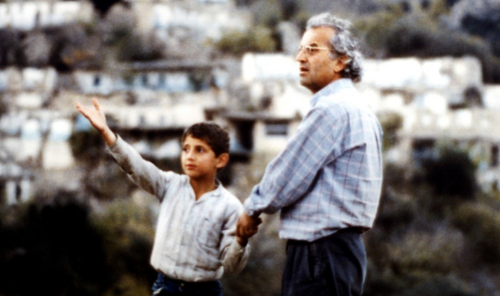

1. Life, and Nothing More…

Also known as “Life Goes On,” this film is Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s portrait of the 1990 earthquake aftermath in Iran. The earthquake killed more than 30,000 people and left devastation all over certain regions of Iran. The events of the film are based on Kiarostami’s search for the protagonist of one of his previous films all over the wrecked lands.

In his journey, we witness how the earthquake has affected the lives of the people and how are they trying to get over all of the damage it has done to them. This film is the second part of the Koker trilogy, following “Where Is the Friend’s Home?” (1987) and followed by “Through the Olive Trees” (1994), and it was released two years after the earthquake in 1992.

As the second film in the trilogy, “Life, and Nothing More…” is a middle point between the straightforward realism of “Where is the Friend’s Home?”, and the continued breaks of the fourth wall that can be seen in the last film of the trilogy. It is crafted in a docu-fictional style where the alter ego of Kiarostami is portrayed by the main character.

This film is a great example of how Kiarostami subverted classic conventions, such as shooting inside a car, to create his own rhythm and cadency that convey a different perspective on cinema and life.

2. Dreams

One of Akira Kurosawa’s last films, a collection of short films portraying the relationship between nature and humankind. The short films are based on the dreams that Kurosawa had through the years, and are told in a style that breaks greatly with some of conventions of Kurosawa’s style.

In contrast to the Classic Narrative that the Japanese masters perfected with films such as “Seven Samurai” or “The Throne of Blood,” in “Dreams” we see a style that bound together the episodes of the film though thematic chains, and does not rely so heavily on dramatic tension.

The short films that comprise the film show different stages in the relationship of humans with nature; it starts with the innocence that a child has and it develops with more cruel and harsh post-apocalyptic portraits. In the film, we also see how a group of men is able to survive in the hardest conditions and how a village is able to live in harmony with nature.

It is in the last episode, called “The Windmill Village,” that a conversation involving humans and their customs with nature takes place. In this conversation, a visitor arrives in the village and talks with an old man who appears to leave in greater peace that the rest of the characters we see through the film.

3. The Apu Trilogy

Released between 1955 and 1960, the Apu Trilogy consists of “Pather Panchali” (1955), “Aparajito” (1956) and “The World of Apu” (1959), directed by legendary Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

The three films of the trilogy were internationally awarded in festivals such as Cannes, Berlin and Venice. In these films, we see the growth of Apu during the early 20th century in rural Bengal; the films portray the struggles of Apu with responsibility, poverty, and his desires to become a writer.

There were two heavy influences for Ray in the making of this trilogy: Italian neorealism (especially “Bicycle Thieves”) and the style of Jean Renoir. These influences can be seen in the austerity the production had and in the preoccupation the Ray had for the mise-en-scene. But these influences did not make Ray neglect what he as an Indian filmmaker could express; the three films have their own style distanced from Renoir and De Sica.

4. Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring

The film, released in 2003 and directed by South Korean film director Kim Ki-duk, portrays the life of a Buddhist monk from childhood to old age. The stages of life are related to the seasons in the title, as the film displayed episodes with decades of distance. The film is split into five episodes since spring is repeated at the beginning and end, inducing a cyclic conception of life.

The film had a positive reception among critics and is often described as film that rather than giving answers, makes the viewer ask them, and also reveals a very specific perspective on life and the passing of time. One of the main traits of the film is the set of a floating monastery in a lake; it is in this monastery where the fils and conversations takes place during the life of the Buddhist monk.

5. My Dinner with Andre

In this film we see the encounter between two friends who see each after they have taken distinct paths several years before. These two friends are the screenwriters and main characters of the film: Andre Gregory (Andre) and Wallace Shawn (Wally).

Through the long conversation, the different perspectives on life that the two friends have are shown through the various topics they discuss. Their conversation can be seen as an analogy between Eastern and Western, or between Europe and the United States in the nature of existence and the meaning of life.

At first Wally is amazed by the esoteric experiences that Andre had with Jerzy Grotowski, involving theater and performances; in these first moments it appears that Andre has a life with much more fulfillment than Wally. But as the conversation keeps going, a side of Wally’s capitalism-based life is start to be thought of as something that Wally is not willing to give up.

The two friends start to disagree and expose their perspective on what is worthy about life and if they think it can be changed. We as witnesses of the conversation are put into the perspective of Wally who after the conversation is left with more questions than answers.