5. Irreversible

Gaspar Noé’s dizzying spin on the most B-movie of all narratives – a rape revenge tale – is the most electrifying film of the century so far. It’s so unabashedly tragic, it’s as if a wormhole opens in the middle of the film’s densely structured thematic landscape and you would drown in it were it not for the unflinching realism simultaneously amplifying and undercutting your misery.

Noé manages to perplex you, with the film’s impossibly elegant back flip that offers a piercing look into time’s construction of a tragedy. He travels through blackened streets and seedy bars, offers comfort in the warmly lit house of our romantic leads, and trauma in the white light of the subway leading to catastrophe.

“It’s safer” a woman tells Monica Belucci’s Alex about the path that would cause irreparable destruction in Alex’s life. Nothing is as it seems, and there is no closure – only a serene simplicity wrapped in a genius narrative gimmick. Yes, someone was killed and someone was raped and beaten with the intent to kill. We read that in newspapers every day. Irreversible cares to tell the tale of lives behind those headlines, hence the discomfort.

4. Come and See

As inviting as that title is, the film’s increasingly infuriated visual prowess is hardly so. Ambulances had to be called in to take viewers for whom the film proved too graphic to the hospital. The history behind Klimov’s classic is vital and harsh, and all that can be said about the film is the same. Its significance not only as a harbinger of wartime truth but as a cinematic milestone handily trumps its insistence on not shielding its audience from the cruelties of the darkest time in human history seen through the eyes of a teenage boy.

Speaking of Aleksei Kravchenko’s immersive, swan-like central performance, it is the beating heart of a film that without it would have simply been the cinematic equivalent of a brick thrown in your face. With it, it’s beautiful, compassionate and consoling. His silence is louder than blood-churning screams, and is perhaps closest to Meryl Streep’s earth-shattering work in Sophie’s Choice than any other performance both in impact and miraculously, in technique.

Come and See is not forgiving. It punishes us for the crimes of our societal flaws, still so deeply entrenched their stains splash on the surface now and then as we try to bury them. It never aims to be perfect, but its visual beauty – an amalgamation of the glorious and the jarring – is some of the most honestly haunting work ever put to screen.

3. A Clockwork Orange

Stanley Kubrick’s filmography is as absurdly brilliant if taken chronologically as it would be any other way. Placed between “2001: A Space Odyssey” – his grand, elliptical, concerto to the universe, and “Barry Lyndon” – a glacial, reflection of the meaninglessness born out of the impermanence of human life, “A Clockwork Orange” is rather akin to a good boy turning naughty to prove a point.

Alex DeLarge, Kubrick’s endlessly quotable and fascinating protagonist is fond of raping, drugs and Beethoven’s Ninth, as described in Anthony Burgess’s monumental book. And while the adaptation is a glorious recounting of those predilections, among others, it’s also a cautionary tale about the perils of a society where choice is not afforded – not just to the innocent, but to the criminal as well.

You punish them, it concurs, but you do not manufacture purity in them. Kubrick’s images are riddled, as always, with great ambiguity and thus the lacing of that violence and inhumanity with a singular visual beauty and swoon-worthy classical music might cause some, as it did Roger Ebert, to confuse it with endorsement. But looking closer, you see the ridiculously inane methods employed by the administration to turn Alex into a good man in the film fail, obviously, but their failure is so spectacularly filmed, it wouldn’t matter what Kubrick was alluding to. We’d be eating off of his hands either way.

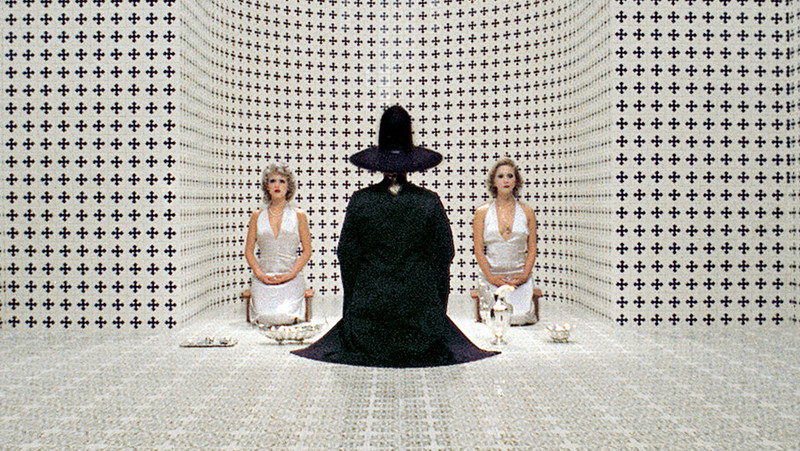

2. The Holy Mountain

Is Jodorowsky’s masterpiece a big, puffed-up joke? Well, if you’re laughing, you’re either too oblivious to its apathy towards our species and its mindless, aimless quest for realizations bigger than its grasp, or willing to shrug off its hardened reflections of politics, morals, industry and society as too abstract to mean anything. Either way, you need to re-examine its vulgar poetry and its shameless political incorrectness.

In all its squishy, swampy, frankly disgusting mannerisms and movements, The Holy Mountain is such an effortlessly transportive and devil-may-care artistic experiment, you spend days unravelling its many mysteries, musing about its dangerously coherent themes and its ridiculously flamboyant grandiloquence. You trust the filmmaker to safely deliver his heightened vision to you, but it’s not in Jodorowsky’s nature to do it in a platter with sections divided for categories of nutrition.

Instead, his film is a plague. It sinks its teeth into you and begins biting until you concede to its demands and let it toy with your emotions and your palate for the, to put it bluntly, radically gross. You will survive and come out of it given so much to think about the way we lead our mundane lives that all those images seem almost necessary, if not entirely hospitable.

1. Sátántangό

If it were told to a cinephile today who wasn’t aware of it, that a seven-hour long Russian film shot entirely in black and white was the most starkly modern and relevant film of the last 30 years, he or she would probably mock the claimant for being out-of-touch. But if Béla Tarr’s mammoth creation is allowed to linger in your consciousness as it does every time you consume it in all its witty, bleak and desperate glory, it’s all too clear what sway it would hold in the court of film.

Aside from its relentless, unfettered tonal darkness, Tarr’s epic is mostly about a small town and the people that inhabit it. It details their lives in the most considered of brush strokes, each lingering, impeccably paced moment allowing you to breathe in their reality and constantly question their existence as an objective viewer.

Is it God’s view Mr Tarr is claiming to possess here? No, simply a man’s. A view so humble in its opinion of administration, power and community as well as harmony, freedom and aimlessness that it might as well be God’s. Any other, more generous or less harsh, could hardly be truer.