Those who are interested in not only cinema but also in any kind of cultural expression such as literature or music will always find in this list one of the debated aspects when it comes to art, censorship, and control. Many controversial films have been banned by censorship bodies or local or state authorities.

The ubiquity of cinema means that films are more than just cinema screenings; film censors see themselves as omnipotent classifiers who control the type of audience that sees a film because they know cinema could be more dangerous than a firearm to fight against tyranny and injustice.

In this list, you will find 10 directors who were banned in their country since their works were considered to be unappropriated. As you will see, the main censors are two figures that have always been the ones who have had the power to decide what can be watched and what can’t: the authoritarian government of different countries, and religious institutions. Taking this into account, it’d be a good idea to bring a quote by the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw from “Mrs. Warren’s Profession” (1902):

“All censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions. All progress is initiated by challenging current conceptions, and executed by supplanting existing institutions. Consequently the first condition of progress is the removal of censorship.”

10. Jean Marie Teno (Cameroon)

The provocative director Jean Marie Teno belongs to the “new” generation of African filmmakers who decided to experiment with different forms and styles. He has used his cinema to talk about the problems of his home country: the political and social issues in postcolonial Cameroon. He uses aesthetic and narrative strategies to combines elements of fiction and documentary, creating an innovative structure.

Teno admitted that it was Daniel Kamwa’s “Pousse Pousse” (1975) that showed him the importance of cinema and the power cinema has in order to show social issues in Africa. One of Teno’s best fictional documentaries is “L’eau de misère” (1998), which deals with the social issue of polluted water supplies in Cameroon.

He has used his socially conscious filmmaking to show the raw reality Cameroonians have been living. Another example of one of his films that criticizes the Cameroonian politics is “Afrique, je te plumerai” (“Africa, I Will Fleece You,” 1992) in which he explores the continuing legacies of colonial oppression.

We should not forget that he started to produce and direct social issue films when he arrived in France in 1978, five years before Prime Minister Paul Biya came to power. It would have been impossible for Teno to screen in Cameroon his films under Biya’s regime, who is one of longest ruling leaders in Africa.

Eight years before Teno arrived in France, the president Ahidjo implemented the state of emergency, thus increasing repression. The president had enough power to enforce the state of emergency and the so-called state of siege.

Life in Cameroon was becoming worse due to emergency regimes. Teno admitted to The Africa Report that “the situation of cinema in Cameroon is terrible,” and he also asked himself that “when you’re in a country where the state is omnipotent, ever violent and always repressive, is there any kind of debate possible?”

9. Jafar Panahi (Iran)

Jafar Panahi was taken from his home along with his wife and 15 of his friends in 2010. That same year, Panahi remained in Evin Prison and although the government confirmed his arrest, the charges were not specified until the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance claimed that he was arrested because he “tried to make a documentary about the unrest that followed the disputed 2009 re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.”

Panahi confessed to Abbas Bakhtiari, director of the Pouya Cultural Center, an Iranian-French cultural organization in Paris that he was mistreated in prison and that his family was threatened. In 2011, a court in Tehran endorsed Panahi’s sentence and ban. Since then, Panahi was placed under house arrest and he was denied the ability to travel abroad.

The ensuing international response to Panahi’s imprisonment condemned the arrest and the ban. Not only did people from all around the world, or even famous directors such as Paul Thomas Anderson or Francis Ford Coppola, urge Panahi’s release, but also 50 Iranian directors, actors and artists signed a petition seeking Panahi’s release.

Panahi had been constantly persecuted by his own government for almost 10 years before he was banned in 2011 by the Iranian government. However, despite the ban, he has managed to work doing what he loves. In fact, one of his best films was made after the government’s unfair treatment.

The docufiction film “Taxi” (2015), starring and directed by Panahi, shows us the life of the director who pretends to be a taxi driver in order to hear pieces of his passengers’ life without expecting any payment in exchange for his work. He has the chance to talk to a conservative-minded man, a pirated video vendor, an injured man and his wife, a pair of old women, and his niece, Hana. When Panahi picks up Hana from school, she wants Panahi to help her to create a short film for a school project, and they both discuss one of the rules given by her teacher: the avoidance of siahnamayi, the idea of showing a negative image of Iran.

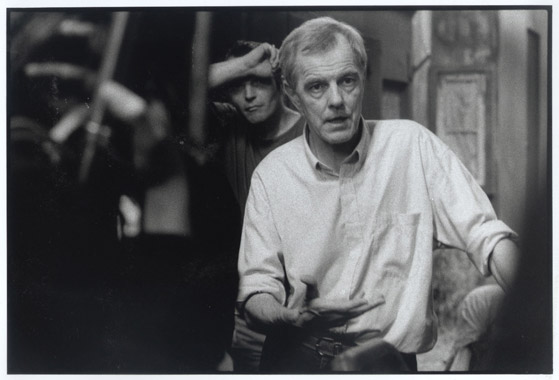

8. Peter Watkins (England)

The English director Peter Watkins uses his mockumentaries and dramatic films to analyse society. In “Punishment Park” (1971), President Nixon decrees the state of emergency in the United States, and he decides not only to send every supporter of the anti-war movement to this “park” located in the Mojave Desert, but also feminists, conscientious objectors, or communists, among others who were considered to be a “risk to internal security.”

The film criticised the police brutality in the U.S., and it was there where the film was heavily attacked when it was released in 1971; it was considered to be a paranoid fantasy, and Hollywood refused to distribute it. The DVD version is introduced by Watkins’ question, which makes everyone assess what is happening:

“With all [that is] happening in the world today, can the film ‘Punishment Park’ remain dismissed as a so-called paranoid fantasy?”

Taking into account the type of controversial cinema he makes, if we go back in time, specifically to 1964, we can see that he has found several difficulties in screening his films. “The War Game,” a low-budget film without any hero and thought to be by many a landmark anti-war film, was banned from being shown on the BBC following government intervention. This drama-documentary, which intended to mark the 20th anniversary of the dropping of the nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, depicts the horrors of the nuclear attack, which made the government decide to withdraw the film since it was thought to contain “inaccuracies.”

In 1966, the struggle began when the film was released at London’s National Film Theatre, but it was mainly through churches and community halls where the film was screened, presented as an educational screening by groups who were against nuclear weapons. However, the BBC kept the ban and it didn’t lift until 1985.

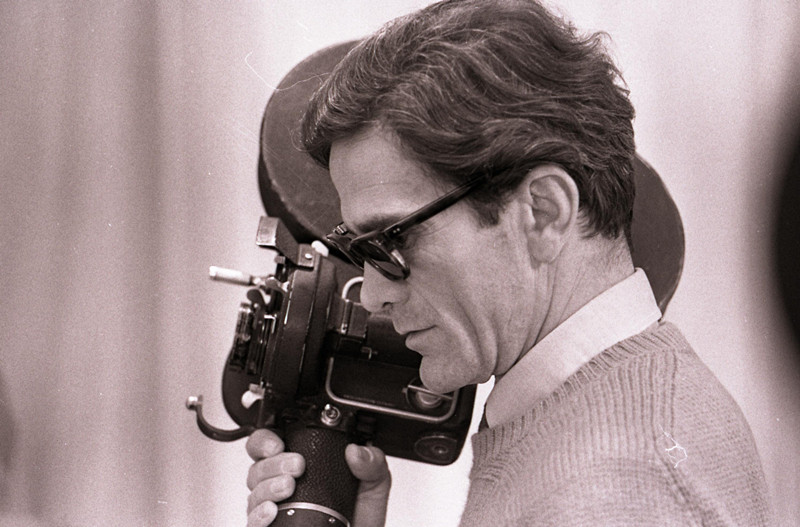

7. Luchino Visconti (Italy)

Between 1939 and 1944, Italy averaged 72 films annually. This shows the importance of cinema under Mussolini’s fascist regime. After WWI, the Italian cinema industry almost collapsed, so Italian movie theatres were forced to screen only foreign films. However, the reluctance of the fascist regime to screen foreign films, and the policy of self-sufficiency, not only economically but also culturally, helped the Italian film industry to rebound.

Mussolini believed that cinema was the most powerful art of the era, and for this reason he paid too much attention to what was screened in Italy. In fact, the regime founded the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in 1935 and it built one of the most famous film production complexes, Cinecittà, in 1937.

Nevertheless, all that glitters is not gold; cinema was supported by the regime, but you had to stick to the fascist principles if you didn’t want to get into trouble. In 1943, the year that witnessed Il Duce’s downfall, Visconti’s first feature “Ossessione” (“Obsession”), based on James Cain’s novel “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1934), was banned in Italy since the director created a protagonist who could be considered to be homosexual.

The protagonist opposed the idea of “manliness” promoted by the fascist regime. The outraged reaction of the church authorities and the Fascist regime banned this film. In fact, the film was even destroyed by the Fascists, but Visconti managed to hide a duplicate of the film.

6. Jan Švankmajer (Czech Republic)

Jan Švankmajer is one of the greatest surrealist directors, not only by his undoubtedly multidisciplinary skills to contribute to the most innovative films and shorts of cinema history, but also because he was one of the few people who dared to fight against the authoritarian communist regime in which Czech Republic was under. For this reason, the most significant influence on Švankmajer is the authoritarian context in which he worked.

Following the Prague Spring of 1968, a revolutionary attempt whose main objective was the liberalization of Czechoslovakia as a communist state, Švankmajer’s film “Leonardův denik” (“Leonardo’s Diary,” 1972) was banned due its implicit critique of communism. Although he was told by the censors not to mix reality and fiction in this short film, the director decided to ignore the censors’ request, and as a result, he was banned from making animated films for seven years.

Once he was permitted to return to filmmaking, he agreed on filming approved literary adaptations such as Hugh Walpole’s “Castle of Otranto” (“Otrantský zámek,” 1977) and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” (“Zánik domu Usherů,” 1981), to name but a few. However, he used in these films irrational images that came out of the unconsciousness to criticise the authoritarian regimes and repression.

Later in his career, Švankmajer was banned again in his home country; this time the short film “Moznosti dialogu” (“Dimensions of Dialogue,” 1982) was censored by the government because it showed the failure of personal and more specifically political communication.