Japanese cinema has been on the decline for quite a few years. The structural issues of the industry and the lack of interest from younger audiences have led the production companies to the secure paths of the family drama and the novel/manga/anime adaptation, which seem to generate the most revenue. This tendency has led to a lack of original movies and the shrinking of the independent industry.

However, deep down in the depths of the industry, something seems to be moving again during the last few years, with a number of new filmmakers presenting extreme but rather interesting new movies, in a tendency that may manage to lift the industry once more, although it is still early for any definite indications. At the same time, the “underground” splatter industry seems to thrive as always.

Nevertheless, with a focus on diversity, here is the list with the 25 best Japanese films of the last seven years, in another compilation that could easily include 50 or more titles and a completely different order.

25. Helldriver (Yoshihiro Nishimura, 2010)

Splatter could be missing from this list, and who else to represent the category but the master of gore? “Helldriver” is another preposterous splatter film by Yoshihiro Nishimura, this time engaging with zombies.

Taku and his sister Rikka are a couple of roaming sadistic murderers who eventually decide to kill her abandoned husband. During the act, his daughter Kika arrives and attacks the couple. Subsequently, a meteorite falls on Rikka, releasing a toxic gas that transforms every resident of northern Japan into a zombie, and her into their queen.

Some years later, the country is split in half by a wall that separates the healthy population of the south part from the zombies in the north. The government hires Kika, who is now a skilled zombie killer, to lead a team of outlaws to the north to kill the zombie queen.

Nishimura, as usual, incorporates as much absurdity as possible in the film, starting with the movie’s titles that appear after almost half an hour has passed. Furthermore, the zombie boxer, the guards with the peculiar helmets, and a fighting scene involving a kind of pole dancing are only a few of the irrational scenes and notions appearing here.

Nishimura’s usual aspects are also present: constant bloodbaths, surreal humor, impressive battles and a rudimentary effort for social remark, specifically concerning drugs and racism.

Eihi Shiina as Kika is remarkable as usual.

24. Villain (Lee Sang-il, 2010)

Being a Zainichi Korean, Lee Sang-il had always a rather different perspective toward film than his Japanese colleagues, which has his films standing apart, despite the fact that they follow most tendencies of the local cinema.

The script is based on the homonymous novel by Shuichi Yoshida. Yuichi Shimizu is a young man living with his grandparents, since his mother has abandoned him. He works as a blue-collar day labourer, and has to take care of his grandparents, which does not leave him with much time to take care of himself or find a girlfriend. To deal with this problem, he frequently enters dating sites, where he meets girls, but ends up paying them for sex instead of trying to form a relationship with them.

One of these girls is Yoshino Ishibashi, a young insurance saleswoman, who has moved into the dorm the company offers, despite her father’s protests. Although she has a “commercial” relationship with Yuichi, the one she truly wants is Keigo Masuo, a spoiled, playboy student who does not share the same feelings. One night, while she has a date with Yuichi, she meets Keigo by chance and chooses to go with him, leaving a frustrated Yuichi standing. The next day the girl is found dead.

Lee does a great job of combining the classic, indie Japanese style with the slow tempo, with a number of sequences that are reminiscent of the quality Hollywood films, and the Korean crime ones. In that fashion, he directs a movie that lingers among the social drama, romance, and crime genres, all the while retaining an impressive balance.

Another trait of his work is that he manages to draw the best from all of his cast, although Satoshi Tsumabuki stands out as Yuichi, in a very difficult role that has him lingering continuously between being good and evil.

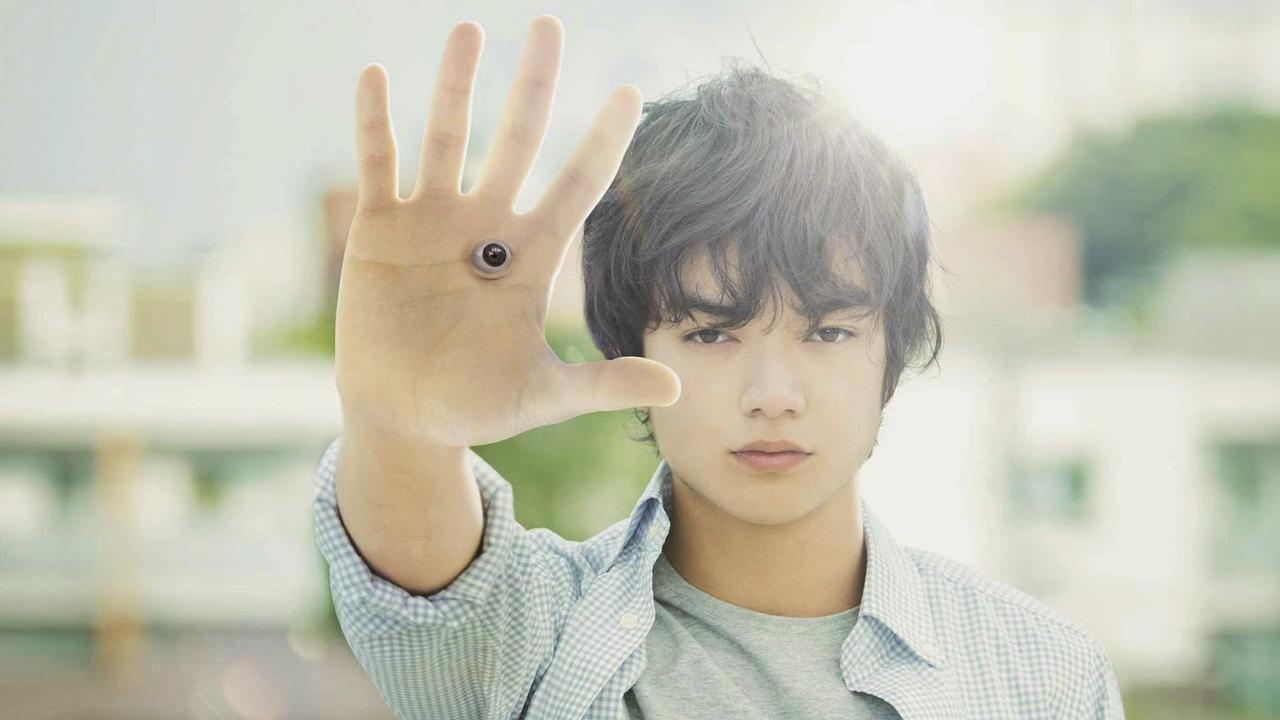

23. Parasyte (Takeshi Yamazaki, 2015)

Another competent adaptation from a manga, this particular film was screened in two parts. A number of alien parasites enter Earth and proceed to enter the brains of human hosts, taking total control of them. However, one of them fails to enter its respective targets’ brain and eventually ends up in the hand of a high school student named Shinichi Izumi.

Izumi, as soon as he overcomes his initial shock, adapts to the idea of a symbiosis with an alien organism, since Migi, as he names it, gives him the ability to confront the other parasites that come after them, at least when they are not feeding from other humans.

In the second segment, and particularly due to a number of dramatic incidents that have occurred in Izumi’s life, he has transformed from a fearful high school boy to a determined vigilante.

Yamazaki’s biggest achievement in “Parasyte” lies with the fact that he managed to accurately portray the combination of slapstick and grotesque aesthetics the original medium entailed. Also of note is the way he uses humor, which appears randomly and unexpectedly at points in the film, as with the scene where Izumi and Migi cook together.

The large budget of the film resulted in impressive though minimalistic special effects that find their apogee in the scenes where the aliens devour humans and the various battles. The film entailed a wonderful cast, including Shota Sometani, Eri Fukatsu, Tadanobu Asano and Jun Kunimura.

22. Rurouni Kenshin Trilogy (Keishi Otomo, 2012,2014)

Based on the homonymous and extremely popular samurai-themed manga and anime, this live-action trilogy is the one that actually instigated the phenomenon of elaborate adaptations.

The films revolve around the adventures of Himura Kenshin, a ronin who has abolished his past as a government assassin. Along with his newfound comrades, he fights against Makoto Shishio and his gang, who want to overthrow the government and plunge Japan into chaos.

Keishi Ohtomo managed to retain almost every aspect of the Kyoto-arc of the original, including the characters, the romance, and the magnificent battles. In particular, in the first aspect, the depiction of the many heroes of the original, is one of the film’s biggest assets, with Takeru Satoh being the Kenshin every fan of the franchise wanted to see.

With actors like Emi Takei, Tatsuya Fujiwara, Go Ayano and Teruyuki Kagawa, all of whom portray their characters elaborately, this trilogy is one of the definite masterpieces of this list.

21. We Shall Overcome (Chie Mikami, 2015, Japan)

Probably the lesser-known category of Asian cinema, since, for a long time, not many of them were released outside the borders of the country. Thankfully, in the last decade, the interest toward the Japanese documentary has increased, with a number of them finding screenings in festivals all over the world, and many on digital media and streaming platforms.

The Okinawa islands are located in southwest Japan. There was intense land warfare in Okinawa when the Allied Forces invaded at the end of World War II and, more than 100,000 locals died in the Battle of Okinawa. After the war, Okinawa was under a different administration of the United States Military Forces than the mainland. As a result, many Okinawans had to surrender their land to the American military bases.

The Japanese Constitution was not applicable in Okinawa during this time. In 1972, control of Okinawa was given back to Japan, but the military bases and the impact of the oppression remained. And now, in 2015, there is a plan to build a new military base, complete with a port, an airfield, and an armory.

The documentary deals with the continuous and desperate struggles of the islands’ inhabitants to keep the US military from building the base, disrupting one of the few virgin seas remaining in the world. The documentary focuses on three central figures of the movement, Hiroji, Takechiyo and Fumiko, examining their everyday life and through them, the history of the islands since World War II.

All three of the aforementioned individuals are unique characters. Hiroji, a relentless leader of the movement, is every day in front of the US military base in Henoko, shouting messages, rallying the rest of the demonstrators and trying his best to obstruct the trucks transferring materials for the new base to the camp. Takechiyo has his whole family (wife and three children) dedicated to the cause, with them even having weekly rituals regarding their protesting. The scene where his older son gives a speech in front of the crowd regarding the cause is one of the most touching in the film.

20. Lowlife Love (Eiji Uchida, 2016)

Tetsuo is a film director who had mild success with a film he shot some years ago, but has not produced anything from that point on and his life is in shambles. He is 39 years old, he still lives with his parents and sister in a small house, and has a constant lack of money. His miniscule income comes from some overpriced acting lessons he gives to a number of students he has promised to include in his next film, and from shooting AV videos that he sells to some Yakuza via his assistant, Yoshihiko.

Eventually, hope appears in front of him in the faces of two new students: Minami, a timid and naive girl who wants to be an actress, and Ken, a scriptwriter. Both of them appear to be extremely talented and Tetsuo believes he will be finally able to shoot a film in the way he wants. Around those characters roams Kida, a suspicious producer and former director; Kyoko, a ruthless aspiring actress; Kano, a former indie director who has become commercially successful; and Kaede, a girl obsessed with Tetsuo.

Eiji Uchida centers his film on the two words of the title. The first one actually describes the various characters appearing in the film, not one of whom appears to be decent or unselfish. The one on the top, however, is definitely Tetsuo, played in a suitably awful fashion by Kiyohiko Shibukawa. His character is immature, lazy, devious, and in constant readiness to exploit everyone around him to achieve his goals of shooting a moneymaking film and having sex.

The overall depiction of the no-budget industry is gruesome, especially for actresses, who are presented as prey for the male filmmakers, particularly because they are intent on shagging their way into movies. The approach the director takes toward them borders on misogyny, although he stresses the fact that since the directors are not even slightly better humans than them, sex is actually their only way to make it.

19. The Boy and the Beast (Mamoru Hosoda, 2015)

Nine-year-old Ren’s mother has recently died, leaving him in the care of relatives he despises, since his father is nowhere to be found. Eventually he runs away and stumbles upon the parallel dimension of Jutengai, which is inhabited by monsters.

The lord of that world is about to retire and is set to appoint his successor between two extremely different characters: the noble Iozen and the loner, bearlike warrior, Kumatetsu. Eventually Ren ends up being the latter’s apprentice, in a peculiar teacher-student relationship. After some years, the adolescent Ren returns to the human world and falls in love.

Hosoda directs a film that was bound to be commercially successful (second highest-grossing film in the year 2015 with a total box office gross of $48.6 million) due to a number of Japanese fans’ favorite ingredients: lonely teenagers, supernatural beings, humorous moments, and a plethora of epic battles.

Furthermore, he presented a number of social messages, including ones regarding the relationship between parents and children, adulthood, the need for education and the benefits of patience, calmness, cooperation and effort, giving in that fashion, depth to the film. However, the film’s main purpose is to entertain, and Hosoda succeeded in that by also presenting many humorous moments, with most of them occurring when Ren and Kumatetsu are fighting.

As is the rule with the director’s films, the visual aspect is spectacular, with the production shouting “big budget” from the first scene. The animation is magnificent with the movement of the characters being realistic and fluid, even when a plethora of individuals is moving simultaneously, an event that mainly occurs in the human city.

The characters are magnificently drawn, with the drawing and the concept of the animals with human characteristics (boars, bears, monkeys, a pig-monk, and the ultimate leader who is a constantly disappearing rabbit), being cute, beautiful and funny.

18. Anti-Porn (Sion Sono, 2015)

Back in April 2016, Nikkatsu announced that it was going to relaunch the “Roman Porno” film series. One of the filmmakers chosen was Sion Sono in probably the most obvious choice. This film is his contribution to the project.

“Anti-Porn” is quite difficult to describe, since the borders between fantasy and reality, and past and present, are almost non-existent. In that fashion, the film starts with Kyoko, a famous novelist and artist who wakes up in a studio bursting with a yellow color, except the toilet, which is vividly red. There is obviously something wrong with her, as she starts to rave about anything that comes to her mind, without actually making sense, like when she shouts “I am a virgin and a whore.”

Things become even more frantic when her assistant, Noriko, enters the studio. She seems to be utterly subservient to Kyoko, who treats her as harshly as possible, both psychologically and physically. A little later, an editor and a photographer arrive along with their three assistants, all of whom are extravagantly dressed, not to mention that two of the assistants are wearing strap-ons.

Sion Sono directs a film that looks more like a theatre play than an actual movie, at least for its largest part, as it unfolds inside a single set. Apart from that, Sono seems to be in his element, as the total artistic freedom he was offered allowed him to let his extreme artistry run amok.

In that fashion, the film includes lesbian sex, plenty of abuse, the protagonist throwing up every time she is about to have an orgasm, and women running around naked for no apparent reason. That is when he is not being completely blasphemous, as the film also shows, a number of times, Kyoko’s parents having sex and her watching, when she was a teenager.