17. Lavoura Arcaica aka To the Left of the Father (2001)

The ideological fidelity of Luiz Fernando de Carvalho to the pages of Raduan Nassar’s book can be perceived initially in the director’s concern for a detailed construction, from the use of the original text, through the intelligent ideas in Beth Filipecki’s clothing, to the functional elegance of the brazilian Gordon Willis: Walter Carvalho, beautifully using the contrast shadows/light, establishing from the beginning the metaphor with the “out of focus” life of the protagonist Andre (lived by Selton Mello), numb by the forbidden passion that he feels for his sister (Simone Spoladore, balancing perfectly in her silence the repressed sensuality and fear).

The young man leads us through the labyrinth of his emotional memory, instigated to awaken from his existential coma by the unexpected visit of his older brother, who is determined to take him back to the bosom of the family. Filipecki subtly evinces Andre’s gradual maturity in costume, since he usually wore light clothing (unlike the gravity in dark tones of his father and siblings), attached to the love of his sister and the almost erotic connection with his mother. He only begins to dress in dark tones when he returns home, accompanied by his brother, not being more psychologically immature.

The speech of the father (spectacular Raul Cortez), who celebrates patience as the greatest virtue of man, comes into direct conflict with the free and curious spirit of his son, who prefers to risk losing himself in the long road of self-discovery, living in fear of stepping outside the comfort of his home. By claiming to be the prophet of his own history, he shows the desire to cut off any tie with society’s code of conduct, confronting figures of authority and denying any form of repression, elements very real in the military dictatorial context that the nation lived at the time in which the book was released.

The orgasm that follows the mechanical act in the initial scene, analogously framed by the sound of a moving train, symbolizes the freedom acquired by the young man in that essentially embryonic room, where loneliness is an important act of learning.

16. Pixote – A Lei do Mais Fraco aka Pixote (1981)

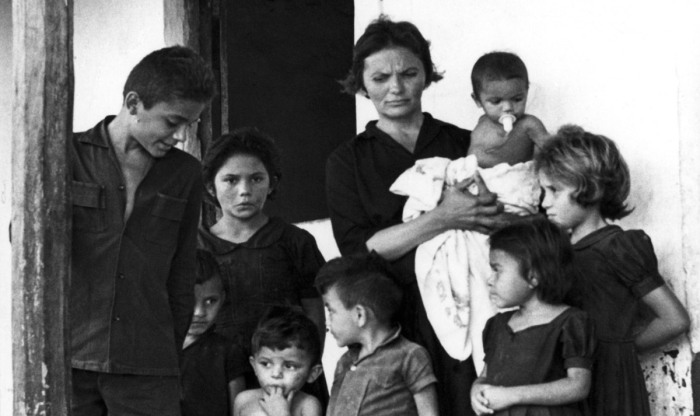

The cruel reality of the streets is evidenced by the director Hector Babenco, in his best work, addressing the loss of innocence in children exposed to a world of crime and prostitution. Little Pixote is sent to a reformatory, but discovers that the system there is corrupt, and that perhaps he was safer away from the clutches of the law. The real life of Fernando Ramos da Silva, the young protagonist reflected the art, he was murdered by police officers seven years later, after returning to a life of crimes.

15. Ganga Bruta (1933)

Started in 1931, this silent film directed by Humberto Mauro suffered considerable delays. The producer Adhemar Gonzaga dreamed of filming the project in the Amazon, which ended up not happening, with problems of money. Still, the production symbolized a professional maturity of brazilian cinema, with internal scenes captured by four cameras, something usual in Hollywood at the time, but new to the Brazilian film industry.

When it was released in 1933, already inserted in a society dazzled by sound cinema, the project had to be adapted to the new demand, with the insertion of audio clips, dialogues, noises and songs. The most beautiful thing to note is that, despite these changes, silence remains the most interesting and creative aspect of the final product.

Sound, an innovation at the time, analyzed today, is the dated element, while Mauro’s visual poetry remains relevant. In its dynamic montage clearly inspired by the work of Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, sexual intercourse is hinted at in a sequence that shows the workers working at the power plant, with the tools operating as phallic symbols.

14. Viagem ao Fim do Mundo aka Voyage to the End of the World (1968)

While waiting for the call to board his plane, a young man searches the newsstand for a magazine. He discovers a pocket edition of “Posthumous Memories of Brás Cubas”, by Machado de Assis.

With a strong inspiration in the works of the french philosopher Simone Weil, symbolized in a nun’s existentialist monologue on the hypocrisy of religion, especially as a political tool, an extremely current point in a society where a candidate who declares himself an atheist would not win votes, the film by director Fernando Coni Campos, although part of the Cinema Novo movement, can be seen as an antithesis of the celebration of sophisticated rebellion in the works of Glauber Rocha, since his visual experimentalism does not seem to seek inspiration in the melancholy poetry of italian neorealism.

13. O Lobo Atrás da Porta aka A Wolf at the Door (2013)

Director Fernando Coimbra’s screenplay, promisingly debuting with the courage of a veteran like Michael Haneke, dares to tread the path of the thriller genre with personality, helped by the great acting of Leandra Leal and Milhem Cortaz. The beautiful and talented actress delivers a frightening performance, conveying in the subtlety of looks the character’s vulnerability, traversing the various psychological stages of her narrative arc, going from sweetness to intense cruelty in a matter of seconds.

Cortaz remains a force of nature, practicing the difficult art of making all the dialogues of the script sound like natural improvisations, always with a touch of irony. He lives a man trapped in a worn relationship, who ends up finding the injection of courage in the risky love challenge he sees in a young woman he has met in public transport, a symbolic leitmotiv representing the unknown factor that hides in the various daily decision-making crossroads in the life of every individual.

12. Terra em Transe aka Entranced Earth (1967)

Glauber Rocha said that he was trying to do something that merged the intellectual cinema that was made in Europe (the rise of the Nouvelle Vague), with Hollywood. Mixing John Ford and Eisenstein. In “Men and Women” he managed to craft his masterpiece, getting closer and more efficiently to his artistic longings.

The intellectual poet Paulo (Jardel Filho) shows himself as a large part of society, desperate to find a safe haven in the promises of some leader, some active voice in the crowd. Its large stature and rocky complexion hide a frail and frightened soul. He embraces the reclusive conservative Diaz (magnificent Paulo Autran), who was useful for a time in his social climbing, but whose varnish was peeling until displaying without modesty a sick megalomania, with a Caesar complex that makes him betray anyone.

There is no way to grow roses in a bad land, you need to change the land. Paulo took a long time to realize this sad reality. Poetry dies when faced with politics. The only incorruptible political act is the one that does not require elections and is not remunerated either: to inspire good values and integrity of character.

11. Casa de Areia aka House of Sand (2005)

The richness of the screenplay complemented by a masterful delivery of the actresses, Fernanda Montenegro and Fernanda Torres, mother and daughter in real life, creates organic poetry, which invites the public to think and get emotional in this unforgettable tale of loneliness directed by Andrucha Waddington.

10. A Hora da Estrela aka Hour of the Star (1986)

It is not difficult to conclude that this beautiful adaptation of Suzane Amaral to the book of Clarice Lispector, faithful to the essence and efficient in its execution, is the best Brazilian film of the eighties, true flower in the asphalt.

The sensitivity of the script, which works with an unusual simplicity in the period, a time when all Brazilian filmmakers seemed to try to emulate the visual cacophony of Glauber Rocha, who in turn emulated french experiments, captivates the viewer in the very first scenes, when we meet the protagonist: Macabéa, lived by Marcélia Cartaxo, the “virgin typist who likes Coca-Cola.” A pure-hearted, naive northeastern woman who has not yet learned to be a slave to cosmetics, the rigid standard of beauty that rules society, practically a baby thrown in the stone jungle, trying to survive the bitterness of men.

By falling in love, feeling lost in the dark core of her existence, or at all costs avoiding silence, for fear that the other, the projected image of her dreams, relentlessly undoes itself in the air of his punished illusions.

Like Kaspar Hauser, she was not accustomed to social contact, without the necessary discernment to guard against the cruelty of the world, she lives on childish daydreams, with her reflection in the mirror always blurred, an important detail that adds more symbology to the plot. The shining hour of her star, the awakening of a timid hope, a feeling she never had the courage to stir up, involves the bittersweet outcome with a cloak of tenderness.

The final sadness, in a strange alchemy, ends up becoming the most graceful beauty, since, analyzing the cruel monsters that surrounded her, a generous chance presented her with the definitive denial of the concept of crooked humanity which, even today, breaks the hearts of those who are genuinely good.

9. Cabra Marcado Para Morrer aka Twenty Years Later (1984)

Eduardo Coutinho made a kind of cinema intensely emotional, original, brave, that forges a judicious and conscious audience, an essential element, mainly because of the way his camera approaches a theme that, in other hands, could become something pamphletary, manipulative, reducing what happened to a simplistic view. Coutinho, as a documentary director, was not a brawler like Michael Moore, but a truly sensitive artist who vanished before the important stories he was telling. He believed that the documentarist should never consider himself more important than the focus of his work.

One sentence, spoken vehemently by one of the peasant’s widow’s sons, crystallizes the maxim that follows poignantly: “All regimes are equal, no government is good for the poor.” When the intoxicating sensation of power clouds the eyes, even the most well-meaning citizen thinks, even for a small moment, to abandon his ideals and turn his back on his values. Character, that magic trait that is independent of any external element, is the only antidote capable of stopping this overwhelming ambition. The goal, once altruistic, becomes the permanence in that corrupt system.

The poor people, though theoretically prioritized by populist regimes, are just numbers that need to be managed, the oil that keeps operating the enrichment gear of those who have conquered power. The poor can eat better, live in a more dignified place, but will never be minimally stimulated by the system to transcend this condition of existential subservience. The cinema, through the lens of Coutinho, acts as a tool that restores the identity of these individuals, injecting self-esteem, repositioning them as citizens with a voice.