Defining a realistic war movie is no easy matter. In some cases there will be excellent realism mixed with complete fantasy. Other try to be extremely gritty and bloody, but miss on the attitudes, tactics, even the weapons! Some are so close to an individual soldier or small unit that it’s impossible to get the idea of what’s going on in the larger battle…which is more realistic from the soldiers perspective, but might be completely wrong in the overview.

Instead of trying to list movies that get absolutely everything right all the time, with no anachronism of word or deed, we will instead look at movies that get important parts right, while accepting that only those who have seen the elephant (as they said during the Civil War) will truly understand. It is not possible to translate whole truth to the screen, which is at base just a fantasy version of anything. Because of this fact, those movies that try hardest sometimes fail worse than those that don’t try so hard.

This list of ten could easily be doubled, because there are a lot of good and accurate war movies, but we’ll have to stick to the few that stand out in particular ways.

10. Ivanhoe

Though not entirely a war movie, Ivanhoe contains excellent scenes of medieval combat, in tourney, in single combat, in the woods, and in a castle. In most movies where swords and spears are the common weapons, every battle instantly devolves into individual fights, with no lines and no way to tell who is friend and who is foe.

Recently several small films have shown much better attention to realistic medieval combat, mainly in television series. Ivanhoe beat them all to the punch twenty years ago, because it came out in 1997.

The armor, weapons and attitudes are true to the period, unlike the original novel. Prince John and King Richard are especially well-done, probably the most accurate versions ever to appear in film. King Richard at one point is missed by an archer and instead of ducking for cover, charges, screaming an incoherent battle-cry while he rides down several of the bandits trying to assassinate him. This is something that seems insane to a modern audience, but was pretty common in the day.

The skill of knights compared to less-trained adversaries, the importance of leaders to morale, and the relatively few deaths among the nobility are all accurate. There are many current examples that include the same kind of realism, but Ivanhoe is an early and excellent example.

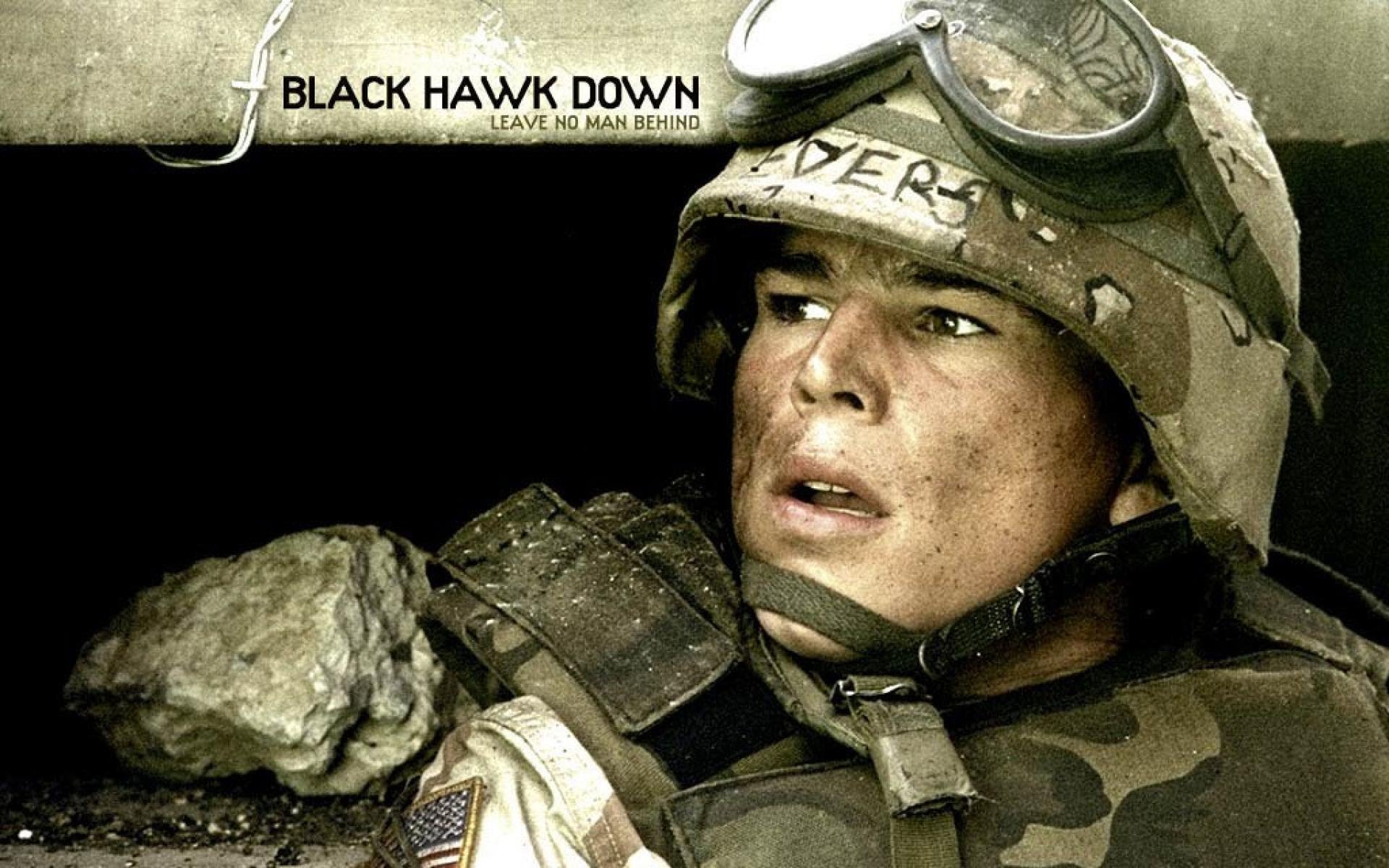

9. Black Hawk Down

Like some of the early movies in this list, Black Hawk Down follows the whole story, giving us multiple perspectives from multiple characters, and tells the story of a police action gone wrong, which is pretty common when the United Nations is involved.

The weapons, tactics and attitudes of this movie are spot on, and the heroism depicted is breathtaking, especially that of Master Sergeant Gary Gordon and Sergeant First Class Randall Shughart.

The Battle of Mogadishu began when several Ranger units and Delta force operators were sent to capture Aidid, the warlord who had been interrupting the flow of supplies to starving Somalians. They captured several people where they were supposed to find Aidid, but he was not among them. On the way back they came under intense fire from all sides, and one of the helicopters, a Black Hawk, was shot down, hence the name of the movie.

Rangers were sent to protect the crash site, and another helicopter dispatched to assist, but it too was shot down, too far away from the other site for the Rangers to reach. Another helicopter orbited the area with a minigun and three snipers aboard, and after being denied twice, Master Sergeant Gary Gordon and Sergeant First Class Randall Shughart were allowed to descend to the crash site to protect the crew of Super Six Four.

They extracted the crew and defended them until overwhelmed by superior numbers and lack of ammunition. They killed at least twenty-five attackers among them, and were posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

It seems likely that the present popularity of snipers began with them. Up until that time snipers were not well-respected by a lot of soldiers, especially during earlier wars.

This movie is gripping and intense, with accurate depictions of almost everything, and a credible American accent from Ewan MacGregor. It is very matter-of-fact in tone, showing heroism almost as if it were a normal day at work…which to some, especially Delta Force, it probably is.

It is especially gratifying that two Medal of Honor recipients were given a bit of attention, because it’s not common enough. Few appear in the movies, even in movies about the battles they fought in, like Sergeant-Major William Carney, who is entirely missing from Glory. Besides Sergeant York and Audey Murphy, few enough are even well-known enough to merit movies of their own, and while Sergeants Gordon and Shughart didn’t have the entire movie dedicated to them, their part is given the attention it deserves.

War is hell, and we ought always to honor those who place their bodies between us and war’s desolation, even if they aren’t perfect paragons of virtue in every other way.

8. Zulu Dawn

Most movies are made about successful battles, but Zulu Dawn depicts the terrible British disaster at Isandlwana, though naturally from the Zulu perspective it wasn’t a disaster. Zulu Dawn follows several characters through the build-up to the battle, including Lord Chelmsford’s fatal decision to divide his forces in the face of the Zulu advance.

The movie takes license in several ways common to movies, especially in personalizing the experience, and perhaps gets much of the way the battle was fought incorrect. There are several accounts, and they don’t all agree, but it is impossible to use them all; they had to pick a few that were close enough to make a coherent story. This may be in fact a false picture of the battle, but at least it’s faithful to at least one contemporary account.

The uniforms in Zulu Dawn are mostly accurate, though there are a few that are anachronistic, but the attitudes and the equipment are all very close to the originals. The preparation for the battle is quite realistic too—actually setting out range stakes before the Zulu charge. Range stakes are very nice, of course, but any modern soldier will scoff at such things. It was a holdover from the Napoleonic era…not because anybody was silly enough to use them in that time period, but because they couldn’t break out of the military system of that time, and adapt it for rifles.

One might guess that the American Revolution and the Seven Years War might have taught the British that it’s not always a good idea to stand in a straight line and shoot in volley when your foe doesn’t follow the same rules, but they were still using old-fashioned doctrine despite their new-fangled weapons. As a much smaller unit demonstrated just a few days later at Rorke’s Drift, it was possible to concentrate fire with single-shot, breech-loading rifles, and concentration of fire is still used to this day.

Instead, at Isandlwana we had a thin line of soldiers spread over too much ground, with not enough bullets to keep up with the approaching enemy. One scene in the movie is something of a myth, but one that is supposedly based on real experiences: the Quartermaster sitting on a big pile of ammunition doling it out a box at a time while dozens of men stand in a queue waiting desperately.

This scene could be apocryphal; nobody really knows, though several accounts of the battle included it. The fact remains that the Zulu captured literal tons of unused ammunition, which could have been expended to repel their attacks.

It is a fact of military life going back to the Assyrians at least: bureaucracy and armies are inextricably intertwined. And as has been demonstrated in many wars, bureaucrats are adept at losing battles. It may be that the much-maligned Quartermaster at Isandlwana was actually innocent, but it does not change the fact that counting bullets when lives and battles are at stake is a losing strategy. In addition, the depiction of how a single bureaucrat can cost many lives is one we all ought to take to heart as bureaucracy again begins to encroach on our freedoms.

One result of the battle was the abandonment of the ‘thin red line.’ Close-order formations were used against the Zulu and in other colonial battles ever afterwards.

7. Gettysburg

This is another made-for-television movie that came out in 1993, though it was also shown in theaters for a short time. Gettysburg is the story of one of the most important battles of the American Civil War, and many of the extras were reenactors who were eager for authenticity.

The Civil War changed attitudes about war that had existed for centuries. In many ways it was the first modern war, and the death-tolls were far beyond what came before. Before that time war seemed to many more sport than anything else, the sport of kings and great magnates. Today it is axiomatic that war is hell, yet it was not always seen so.

Many took it for a great adventure, and the specter of death seemed far away…until the rifle-armed armies of the Civil War tore through each other in greater carnage than had ever existed before. Gettysburg remains the most costly battle ever fought in the Americas to this day, and heaven help it remain so!

The movie Gettysburg follows generals and officers and gives an excellent overall picture of the movement of the troops. It shows the hinge-pin of the battle, when the Confederacy came within a few inches of turning the Union flank and the battle with it.

Jeff Daniels (yes, THAT Jeff Daniels, of Dumb and Dumber) plays Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlin, commander of the 2nd Maine Infantry Regiment, and the movie follows his reasoning and his astonishing fight his understrength unit made to hold that flank. And it shows the true glory and horror of Pickett’s Charge, the ‘high water mark’ of the Confederacy. It does this without the gore and blood that are considered fun today.

6. Zulu

Taking place just days after Isandlwana, the battle at Rorke’s Drift was much smaller in scale. Isandlwana cost the lives of about 1,300 British and native troops, after an attack by about 20,000 Zulu. Between two and four thousand Zulu attacked Rorke’s Drift, against about 140 British troops, and against the orders of King Cetshwayo. Rather than forming a long perimeter with a thin line of soldiers, the two lieutenants who lead the British kept to a relatively small defensive formation, and successfully defended the station with their small force.

The final part of the battle in the movie has the British standing in three lines, belting out volley after volley in almost a single roar, and at point-blank range. While the accounts of the battle vary, the movie demonstrates the effectiveness of concentration of firepower, which later was demonstrated even more by the combined arms theories in WWII.

There are a lot of historical errors in this movie, especially the apocryphal salute by the Zulu force as they march away defeated. Most of the troops were English rather than Welsh, and the tension between Lieutenants Chard and Bromhead was an invention of the movie. Private Hook, in a particularly glaring example, was not the malingering ne’er do well depicted. However one thing they got right was the power of shooting not just in unison, but concentrating that fire in a small area where it can slow down even the recklessly brave and tenacious Zulu.

Some of the attitudes in the movie are certainly anachronistic, as it was filmed in 1964 when cynical pacifism was becoming more common. Lieutenant Chard continued in the army until he died in 1897. Anachronistic attitudes are perhaps the most common error in war movies, but despite these errors, the depiction of the actual fighting is very well done.