German Expressionism was one of the most influential artistic movements of the early XXth century, especially when it comes to cinema. Quintessentially, its artists attempt to seek a deeper meaning in reality, sacrificing realism for the sake of the emotional effects of exaggerated, distorted forms. This way, the subjective perception of life takes control over objective descriptions, focusing on the inner world, instead of the outer.

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact aspects of Expressionistic cinema, but it’s quite easy to find works that fit its overall premise. Although the outlines were set between the 1910s and 1930s by German masters such as Fritz Lang, F.W Murnau and Robert Wiene, many filmmakers from other times, places and backgrounds gave their own contributions to the seventh art in a similar fashion.

This article seeks to point and analyze examples of German Expressionism that were not made at the peak of this movement, but share stylistic, aesthetic, and/or thematic ties with this particular brand of filmmaking.

Traditional Noir and Neo-Noir movies were deliberately taken out of this list, as their direct heritage from German Expressionism (especially movies such as M) is overtly clear. The following list proposes a more diverse approach to influences, from French experimentalism to Hollywood blockbusters.

1. Pi (Darren Aronofsky, 1998)

Pi tells the story of Max, a lonely and obstinate mathematician in an unrelenting quest to find a pattern within all digits of Pi, an arrangement believed by him to explain nature. When his work starts taking form, two parties attempt to take his work for their personal gain: Marcy, a business woman who wants to apply his pattern in the stock market, and Lenny, a Jewish numerologist, bound by the belief that Max has uncovered a secret code in the Torah, regarding the true name of God.

In many ways, Pi echoes the work of German expressionist director Paul Wegener, specially his trilogy “Der Golem”, a series about a monstrous creature built by a Jewish mystic (the Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel) to defend the Jews of Prague from the Holy Roman Emperor’s anti-Semitic decree of exile.

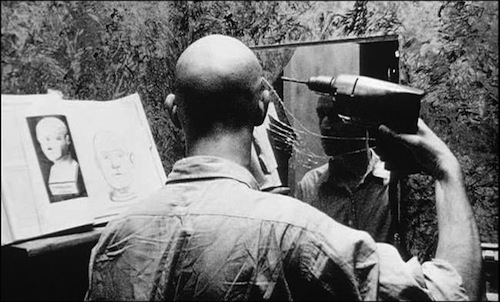

To the right, Wegener’s Rabbi; to the left, Arronofsky’s Rabbi

The strong over-exposition of Pi’s cinematography, jam-packed with both brightness and contrast is a very clear nod to the chiaroscuro aesthetics of Wegener’s films. The shadows and saturated light seem to externalize Max’s unstable and obsessive mental condition in the same way Wegener uses it to accentuate the horrifying and Frankenstein-like nature of the Golem.

Aronofsky’s movie does not borrow only the visual and plastic themes of Wegener, but also many thematic motifs. In several ways, Der Golem is a three-part dramatic piece about the destructive nature of creation, if not treated with its due responsibility, the terrors of using deep formal knowledge for sociopolitical uses, and a magical, mystical approach to science.

This becomes even clearer in the analysis of both movies’ scenarios. Rabbi Loew’s lair is characterized as a dark cave, filled with mysterious scripts in Hebraic. In parallel, Max’s apartment, his place of study, is a dim place, crammed with enormous computers, with walls overflowing with numbers and mathematical symbols. To the layman, the writings of math are just as occult as ancient religious lore.

To the right, Max’s apartment in Pi. To the left, Rabbi Loew’s lair in The Golem

One of the main landscapes of the Golem series, the medieval city of Prague is shown as a shadowy, claustrophobic maze, a recurrent choice in German expressionistic city design. In Pi, the setting New York seems to mime the disorder of urban life, with many shots taking place underground, giving a suffocating impression of the cosmopolitan environment.

Being thus, one can infer that Pi represents the unsettling fear of the scientific unknown. Even though it’s set in the post-modern era, it’s clear that old insecurities of early XX’s century industrial society still lurk today.

2. The Wall (Alan Parker, 1982)

Pink Floyd’s visual aspect as a band is not something to be slighted. From their light-hearted psychedelic inception to their darker tone in the seventies and eighties, the band’s experimental ambitions more often than not had its roots on artistic movements not limited to music.

In 1982, Pink Floyd releases the musical film The Wall; A character study of Pink, a rockstar whose life was shattered by drugs, emotional instability and troubled family relations, The Wall relies heavily on symbolism lain mainly by Surrealist and Expressionist artists.

For starters, the very poster of the movie clearly references Edvard Munch’s most famous work “The Scream”, one seminal work of expressionist art. This picture of the screaming mask, a representation of Pink’s despair, sets the ground for the film’s overall style and recurrent themes; madness, oppression and a longing for freedom are stated in this very concise drawing.

Throughout the whole piece, non-linear in sequence, the main character’s struggle with madness is evident. The general lack of dialogue compelled the director Alan Parker to rely heavily on the use of pure visual storytelling, many times using German Expressionist imagery to convey his message.

This theme and the way it unfolds can be easily linked to Robert Wiene’s 1920 classic “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”, a silent film about the fantasies of Francis, a hospice internee, about the tyrannical authority figure, Dr. Caligari. This movie is linked to the wall in several instances:

The use of oneiric, distorted landscapes to express divagations of the mind

The negative and exaggerated characterizations of figures of authority

And even a clear reference in the use of shadows and face shots

These examples are not the only German expressionist elements present. Other features include: the symbolic use of mirrors and other points of reflection, anthropomorphism and abstractionism.

Reflective surfaces, a pervasive mise-en-scène for old-time expressionist directors, are used indiscriminately. In one instance, the mirror is used as a window to Pink’s desire to free himself from the burden of adult life; he faces himself deeply, and shaves every single hair of his body, in a cathartic display of his wish to be reborn. Another reflective object present throughout the entire movie is the television, a screen through which Pink tries incessantly to escape his somber reality and numb his troubled self.

The anthropomorphism is particularly tangible in the animated bits. Vagina-shaped flowers that bite each other, singing snakes and a dummy facing trial are samples of non-human things behaving like humans.

Abstractionism, the artistic way of expressing feelings and situations through the use of non-literal imagery, as in shapes and colors, is very present throughout the movie. One could say that the whole film is abstract in nature, as it bases his plot on the divagations and exaggerated analogies to Pink`s states of mind.

The Wall`s argument is not to be comprehended through its factual narrative, but to the way the main character`s feels and subjectively interprets each interaction. In a metalinguistic sort of way, Parker presents us to a deliberately confusing motion picture, in which is hard to separate the true chronology and Pink`s ramblings, the same way Pink himself is having difficulties doing the very same thing in his struggle with madness.

3. Nosferatu, the Vampyre (1979)

Werner Herzog’s filmography has clearly been influenced in a major way by German Expressionism movement. The unsettling vibe of Even Dwarfs Started Small (1985), the supernatural-surrealist feeling of The Wrath of God (1972), and the black-and-white noir suspense of My Son, My Son, What have ye done? (2009) are examples of the recurrence of subjective, emotional and often violent themes under a romantic and dark aesthetic perspective.

“Nosferatu, the Vampyre”, a stylistic remake of F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), pays homage to the German expressionist era. A love letter to the genre, Herzog’s film excels in conveying all the grim, theatric atmosphere of the original silent and black-and-white movie to a modern, colorized, spoken film.

The original movie is an unlicensed adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, originally casting Max Schreck as the Count, renamed “Nosferatu”. In the 1979 version, the main character is played by Klaus Kinski, conserving the grotesque and disturbing appearance of Schreck; pointy ears, pale skin, long nails and teeth are an externalization of the Vampire’s diabolic essence, condemned to live forever in seclusion.

To the right, Klaus Kinski as Nosferatu. To the left, Max Schreck as the same character

Herzog’s Nosferatu, given the liberty of dialogue, focuses much more in the solitary nature of the cursed count, instead of primarily in his dreadful nature, as in the original. The use of shadow and light, make-up and staged acting serve mainly to send the message of the vampire as both victim and victimizer, due to his condition.

4. The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980)

A tragic biography turned fairytale, turned tragic again, the Elephant Man focuses on the relationship between John Merrick, a severely deformed young man, and Sir Frederick Teves, the doctor/father figure who rescued him from leading the life of a circus freak.

This piece strays from David Lynch’s usually surrealistic style, in favor of a more traditional script, focusing deeply on character development and on one philosophical question: What does it mean to be a monster?

The monster is a very present archetype in the German Expressionist movement. From the vampire from Murnau’s Nosferatu, to the schizophrenic outsider that is Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, what is a “monster” seems to be but a point of view.

Following the tradition of Romantic novels, as seems to be the inspiration of many expressionist auteurs, the spectator Is invited to develop empathy for the monster, to try to understand him rather than destroying him. In many ways, the Monster is a misunderstood social outcast, turned pariah due to prejudice, violence and an absolute, and ultimately unfair, moral balance.

Four characters deserve special attention. At first we have John Merrick, the Elephant Man. A congenial disease has deformed his face and stalwartly blistered his skin, providing him with a grotesque appearance. However, this monstrous outside hides a sweet, intelligent, interior. Perhaps the most compassionate and sensitive of all characters, Merrick develops a taste for intellectuality and seeks avidly to communicate with other human beings.

Then, we have its counterpart, the unscrupulous freak show owner Bytes. An unkind and greedy man, Bytes mistreats and forces Merrick to be exposed in his circus, like an animal in a zoo, as the most hideous creature on Earth. Despite his cruelty, he is not simply shown as a quintessentially evil man. Rather, his wicked ways are inferred to be the reflex of years of poverty and harshness, poured upon a man who succumbed to the urge to use lateral violence.

The Night Porter, an amoral man, uses his access as the hospital caretaker to sneak people in Merrick’s chambers, in order to profit from his misery, just like Bytes did. He represents the lowest class of the social structure; always accompanied by whores, drunkards and other misfits, pointing their figures as if to mock the only one who is less fortunate than them.

At last, there is Sir Frederick Teves. A bourgeois gentleman of the medic class, he meets Merrick as a whim of his own curiosity. In the first half of the movie, it’s implied that he wants to use the Elephant Man’s deformity as a trampoline for his own career as a doctor, exposing him in medical conferences to gain notoriety as a scientific pioneer.

As the plot progresses, they develop an interesting mix of friendship, patient-doctor and father-son relationships. Still, members of the upper class keep visiting Merrick for the sake of their own curiosities.

In the end, The Elephant Man is a well-rounded social critic regarding the nature of mankind. Characters are not only individuals, but also firmly formed by their socioeconomic upbringing, not being good, or bad, but a moral kaleidoscope.

In order to point this chiaroscuro, blurry and greyish scope of characters, Lynch opted for a highly expressionistic aesthetic tone. Black-and-white filmography, solid use of light and shadows, theatric performances and camera angles give this motion picture a very pre-war Germany feel.

5. Mephisto (István Szabó, 1981)

Goethe’s play “Faust” is a landmark of both romantic literature and German culture in general. The tragic narrative of Faust, an ambitious alchemist who sets a deal with the devil for his soul in exchange of knowledge, has resonated in many other medias; Lord Byron’s poem Manfred, many of Robert Johnson’s songs and Jules Perrot’s 1848 ballet are just examples of its legendary influence in art.

The tale’s gloomy and dramatic tone makes it a natural choice for a German Expressionist film adaptation. Obscure, mystical themes, the incessant search for meaning through power, and the overall feeling of uneasiness inherent to the plot were then represented through the grim lenses of F.W Murnau, in 1926.

István Szabó’s 1981 movie Mephisto draws inspiration from both the Goethian legend and the expressionist movement. It tells the story of Hendrik Höfgen, a promising stage actor in the 1930s, which starts to collaborate with the Nazi Party for fame and fortune, and, especially, the leading role in the play Faust.

Mephisto’s relationship with expressionism goes beyond simple spur. The plot itself is an adaptation of Klaus Mann’s roman à clef Mephisto that tells the story of Gustav Gründgens, a very influential late German actor (Who appeared in expressionistic films such as Fritz Lang’s M, in 1931) and his political and social relationships.

Höfgen, Gründgens counterpart, is then aptly played by actor Klaus Brandauer in a very histrionic matter, as if to mime the exaggerated style of early German theater actors. This is particularly clear in any of the scenes in which the characters are acting in plays.

Gustav Gründgens as Mephisto

Klaus Brandauer as Hofgen (Characterized as Mephisto)

The plot, the acting, and, finally, the metalinguistic scenes of plays, reference the old days of German expressionism in many ways. Albeit Szabó’s more concise and realistic pace and visual identity, the groundwork was clearly laid in the 1920s.