The year 2017 has been quite a strange year for the Japanese movie industry after the rather successful previous one, which was shaped by the reintroduction of the Roman Porno series, the new Godzilla films, and “Your Name.” The industry is still dominated by manga adaptations and family/social dramas, but this does not mean that there are no unique or even hopeful films and creators out there.

In that fashion, a couple of new filmmakers filled with potential made their appearance; Takashi Miike continued to prove that he is the best director in adapting manga; Sion Sono returned to his exploitation roots once more with great results; and Sunao Katabuchi gave us a great anime, which seems to take a different approach to the medium, both technically and in theme.

Yoshihiro Nishimura continued his legacy in the Japanese splatter; Yoshitaka Mori gave us a great biopic; Kyoko Miyake shed light in the concept of “idols”; and Takahide Hori presented a great stop-motion spectacle.

Some films may have premiered in 2016, but since this occurred at the end of the year, I took the liberty of including them.

With a focus on diversity, here are the 10 best Japanese films of 2016.

10. BAMY (Jun Tanaka)

With a miniscule budget of 700,000 JPY (about $6,300), Jun Tanaka attempted to present a new take on the ghost (horror) story genre. The film premiered at the Osaka Asian Film Festival in March.

The introductory scene immediately sets the rather unusual tone of the film. Fumiko Tashiro is going up on an exterior elevator when she witnesses a red umbrella flying outside the skyscraper she ascends. Some moments later, she is leaving the building and the same umbrella crashes in front of her on the street. The event alarms her and a passerby, who turns out to be Ryota Saeki, an old acquaintance from college.

The story then flashes forward a year later when the two of them are engaged and have started living together. However, Ryota has been hiding a secret from her all this time: he has the ability to see ghosts, in a trait he does not understand and has made him somewhat neurotic. As time passes, his psychological status worsens and jeopardizes both his upcoming marriage and his work (in a warehouse). At the same time, he meets another woman with the same ability, Sae Kimura, who is even more terrified than he is. One more unexpected event complicates his life even more.

Tanaka stated about the concept of the film: “The red thread of fate – an East Asian myth of a thread that ties destined lovers together – is nothing but a curse. We cannot will miracles to happen; they are forced upon us, abruptly and violently, by an unfathomably great power. One cannot escape it, one cannot resist it. The mythical thread then, if it exists, is surely something monstrous. Faced with such a force, man is always small and powerless. This miracle picks its targets arbitrarily, toys with them, and will not relent until its thread has drawn the fated pair together.”

This point is represented, visually, by the almost omnipresent red umbrella, who symbolizes the above red thread, the connection between Fumiko and Ryota, which seems impossible to cut. The presence of ghosts represents the second point, about the lack of control people have over their fate, and in essence, their lives.

In that fashion, Tanaka communicates a rather pessimistic comment, which has people as puppets of fate with little or none authority upon it. While the message is significant, the relationship between the two protagonists do not justify such a strong connection, since it seems like a usual, even uninteresting one, where the woman has the dominant role of the boss-mother and the man the one of the absent-minded man-child. Furthermore, the highly surrealistic ending sequence makes the message even more confusing and abstract, as the supernatural seems to give its place to the fantastic.

On the other hand, the aesthetics are almost without a fault, particularly when one considers the budget of the film. The cinematography is impressive, as the tints of grey that dominate the movie provide a very atmospheric setting, where horror, confusion and insecurity seem to thrive. In this background, the portrayal of the ghosts, whose faces are always in the shadows, never actually appearing on screen, become even more ominous, as it also justifies Ryota’s psychology, who seems to witness them everywhere.

This imaging highlights the use of lighting in the movie, which is on a very high level. The framing is also very accomplished, presenting some interesting perspectives of the action in connection to each setting.

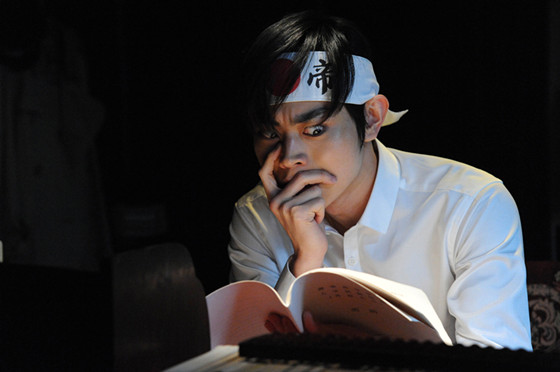

9. Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High (Akira Nagai)

Evidently, Japanese cinema at the moment is swamped in manga/anime adaptations, a number of which are of dubious quality, to say the least. However, among the plethora of similar productions, some manage to stand apart. “Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High” is one of those exceptions.

Based on a manga by Usamaru Furuya, the story takes place in the Showa era (1926-1989) and revolves around Teiichi, a high school student whose sole wish is just to play the piano, but after his father’s strict behaviour and a hit on the head, he decided to become the Prime Minister and eventually created an empire of his own. Having just been accepted to one of best schools in the country, with a cradle of politicians he starts paving the path to make his dream come true. With the help of his devoted (and in love with him) sidekick Komei, Teiichi unashamedly becomes the “dog” of Roland, the extremely blonde chief-candidate for high school president.

In his efforts, Teiichi has to face Kikuma, his rival since childhood, in a competition that has been going on since their father’s time; and Dan, a poor boy who tries to pay up his father’s debt and take care of his sibling, and has become quite popular in school due to his his adamant character and his prowess in sports. Roland’s leading opponent is Okuto, a shogi genius who wants to change the elections into a more democratic procedure, including all the students and not just the members of the council. As the race continues, intrigues, treacheries and the shifting of sides take place, as the student’s parents also get involved in the game.

“Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High” includes a number of the elements all manga adaptations seem to include, with the hyperbolic acting, the crude comedy, and the abundance of motley colours and absurd characters. However, what makes the film stand apart is the way it presents school politics, in a fashion that lingers between a parody of the actual political situation in the country and an intricate game that maintains the tension to the last moment.

At the same time, Akira Nagai analyzes his characters quite well, making a point of demonstrating that their father’s behaviour is the main reason for their scheming and corrupt behaviour. This element also symbolizes the fact that the issues with the current political system in Japan derive from the previous generation, who does not seem eager at all to let the new one “shine.”

8. Kodoku Meatball Machine (Yoshihiro Nishimura)

Yuji is a 50-year-old bill collector and he truly sucks at it, as he cannot get money from anyone, and occasionally he is even stripped from his own. Furthermore, he lives alone, and everyone in his life seems to try to take advantage of him. His boss; his mother, Kaoru; a girl from his bookstore he seems to like who introduces him to a cult; and the members of a sex club who initially draw him in order to comfort him, but at the end they beat him and leave him with an exuberant bill.

If that was not enough, he is diagnosed with cancer, with the doctor suggesting that he just has a few months to live. A bit later, he meets a strangely dressed woman who encourages him somehow, which makes him more confident and results in him finally managing to receive some money from the people he is supposed to collect from.

Alas, around that time, aliens invade the Earth, engulfing an area inside something that looks like a giant class, and they start invading human bodies, taking control of them and transforming them into NecroBorgs, a kind of biomechanical monster, and attacking anyone in their path. Yuji manages to survive the transformation process as his host is killed by his cancer, and sets on a path to fight the aliens in order to save Kaoru. A team of martial artist policemen, who had previously hunted him after he was blamed as a killer after a fight with Kaoru’s brother, help him in his mission.

Nishimura takes a totally unexpected approach to the film, as there is almost no gore for the first 20-25 minutes, with the aesthetics being very close to the ones implemented in Sion Sono’s movies. The scenes in the cult’s “church” and the one in the “massage parlor” are distinct samples of this tendency, although the references to “Tokyo Gore Police” are not missing.

In that fashion, he manages to analyze his main characters, Yuji and Kaoru, quite a bit for a splatter film. At the same time, he parodies many concepts and tendencies of contemporary Japanese society. The police and martial artists, who are presented as fanatic jingoists of shorts, with one of them mocking Jackie Chan’s style in both appearance and fighting style, where he uses two stools as weapons.

The cults, who just want to take money from the people they draw in; the massage parlors, who do the same in most obvious ways; the relationships between bosses and employees; the way the public misjudges what they witness, since people always assume the worst. Most of all, though, the sci-fi concept of aliens invading human bodies.

7. Tokyo Idols (Kyoko Miyake)

“Tokyo Idols” portrays the dream of nearly 10,000 teenage girls in Japan who consider themselves “idols” and perform to entertain their fans. The majority of their “fanbase” is composed of middle-aged people (mostly between 40-50 years old) and their obsessions for these teenage idols. The docu-drama tries to bring out the life and career of these idol girls through a completely different and complex sexual perspective, touching the socio- economic life in Japan in an introspective manner.

Rio is a teenage idol with number of fans and followers. She is 19 and approaching towards the end of her career as an idol, which ends as the girls mature or become “strong women.” She wants to pursue a career as recording artist. Rio’s best fan (as the film portrays) Koji spends thousands of dollars on her. Koji is 43 and attends most of her concerts and even takes part in the music videos, dancing beside Rio. He considers himself a hardcore fan of Rio or an “otaku” as is the term in Japan.

Koji attends all her promotional and handshake events as well. The handshake event is special event where the fans get an opportunity to meet and shake hands with their idols and can take photos with the girls after paying a specific amount for it. The narrative moves on as Rio launches her alternative career by creating “Rio Trans-Japan Campaign.” The film continues under the shadow of a platonic relationship between Rio and Koji, with a flair of a strange sexual feeling and a dream far from reality.

The journalistic approach of “Tokyo Idols” makes it more informative and questions the current socio-economic condition of Japan. It highlights the lifestyle and gap in the relationship between men and women, where older men do not intend to have steady relationships and continue to search for their lust in teen idols.

And strangely, the lust has no sexual connection, and even a handshake with the idols for a few seconds gives the fans a feeling of sexual satisfaction. It highlights a stressed out society failing to take on the burden of economic pressure (or something else?), who chase a dream that is nothing but an illusion in most cases. The idols mostly lose their fanbase as they cross the barrier of “teen” and strangely, their purity and acceptance lie on their virginity to all the fans and followers.

6. Blade of the Immortal (Takashi Miike)

“Blade of the Immortal” is based on Hiroaki Samura’s long and extremely popular homonymous manga saga. A short prologue in sharp black and white sets the mood and introduces us to Manji, a feudal Japan samurai who’s facing a horde of hundred rough bandits that threaten his little sister. When the hooligans cowardly kill the girl, Manji’s reaction is a carnage, and he kills them all. Desperate and critically wounded, the samurai seems to accept death as a benevolent relief, but a mysterious veiled Nan rescues him, inserting a handful of Sacred Bloodworms into his bloodstream.

These restorative worms will thrive in Manji’s veins and will give him the supernatural power of immortality. Fifty years later, we find the super Manji alive and kicking but not particularly pleased to be immortal, living like an outsider in an isolated hut. He is soon contacted by little Rin, the daughter of a local Kendo sensei who has been killed by the icy Anotsu, the head of the infamous Ittō-ryū gang. Manji learns from Rin that the Ittō-ryū is undergoing a sort of globalization project, inviting all the small schools and dojos to amalgamate into a massive mixed bag of a martial art institution.

The senseis have little choice, though, as they are mercilessly killed upon refusal. This had been Rin’s father’s fate and the girl is now out, looking for revenge and a mentor, and the resemblance to Manji’s little sister hits the samurai’s right button.

Therefore, this odd couple (comparisons with “Logan” are inevitable) embarks on a quest after Anotsu’s punishment and along the way, they meet a stream of colorful foes.

From this point onward, the narration turns into a bizarre mode, very adherent to the concept of a manga “series,” where each opponent is a chapter “per se,” almost a manga volume in its own right, in contrast with the usual manga-to-live-action adaptations where the script tries to merge the episodes into a whole narrative line. Interesting as it is, Takashi Miike’s experiment risks dragging the movie, and at two-and-a-half-hour runtime makes it a bit repetitive, though always fun and visually dazzling.

“Blade of the Immortal,” like “13 Assassins,” belongs to the collection of Miike’s calmer and more well-mannered movies, far from the wacky surreal ones. At the same time, don’t expect a traditional chanbara. The plot is spiced up and enriched by touches of supernatural and frequent comedy shots and the parade of challengers on our heroes’ path is a gaudy bunch of punks, totally oblivious of any historical consistency.