5. Battleship Potemkin (edited by Sergei Eisenstein, Grigori Aleksandrov)

This is one of the finest examples of editing in film history, and the name Sergei Eisenstein is tossed around frequently in any introductory film course. There’s a reason why: he revolutionized the relationship different cuts could have. Sure, there are some other big names when it comes to the earliest examples of cross cuts (D. W. Griffith, Dziga Vertov, to name a few), but there is something about the iconic Odessa Steps sequence that simply could not be matched.

The viciousness of each shot makes every jump cut feel like a stab to the chest, as you watch the gore-filled horrors that shook up a village. Throughout the rest of the film, you will find editing that was way ahead of its time and feels right in place with the films of today. There are a number of early examples of silent films with great editing, but they won’t get better than “Battleship Potemkin”.

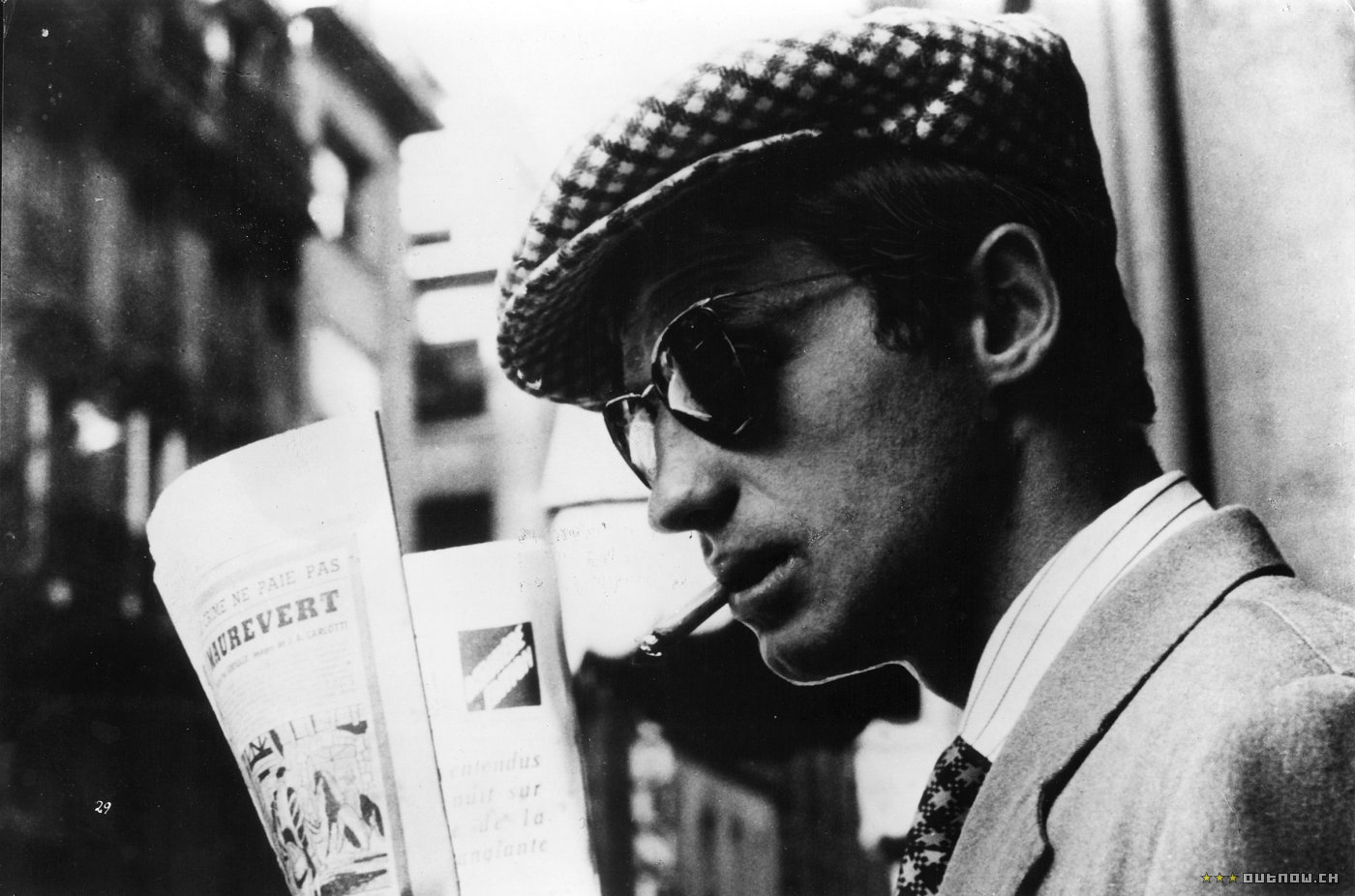

4. Breathless (edited by Cécile Decugis)

This is the most unorthodox entry on the list. Movies that broke the 180º rule (where a camera cannot cross the 180º line when two characters talk, or else it breaks the illusion of a conversation being watched in a realistic perspective) and had continuity flaws were lambasted on the “worst editing” list. The difference here is that “Breathless” is a modernist masterpiece, where French New Wave bad boy Jean-Luc Godard tried to break every rule in the book.

The editing work is no different, and “Breathless” has become the rarest of exceptions that is brought up the most in Film 101 classes. The jump cuts that disrupt time, space, linearity and semblance are not a series of mistakes but instead a re-evaluation. The slick pacing and the sleek dialogue make these razor edits all the more slippery, and you will find yourself coasting through these cuts more than you would ever expect.

Roger Ebert compared this film to “Citizen Kane” in terms of its visionary traits; “Citizen Kane” showed how you could depict the world in cinematic form, whereas “Breathless” showed how you could depict the world in your mind on film.

3. City of God (edited by Daniel Rezende)

In Fernando Meirelles’ crime epic “City of God”, the world got an introduction to modern Brazilian cinema (especially when critics like Roger Ebert and Richard Corliss highly sung its praises). Part of the electricity that came from this film’s thrills is due to the lightning sharp editing work by Daniel Rezende. His work involves many quick cuts, but none of it feels like a headache-inducing experience. If anything, the quick cuts are to create something as opposed to hiding something.

In “Catwoman” (featured in the number one spot on the “worst editing” list), the editing work was to hide the incapability of the actors performing stunts and the director’s lack of true choreography. In “City of God”, the cuts can create an alarming passage of time to recount the amount of crimes one has commit.

It can also show many perspectives of a traumatic experience, as all eyes are fixated on the crime at hand. Rezende’s editing speed is so smartly used that he probably did the best job getting away with using so many cuts.

2. The Good, The Bad and the Ugly (edited by Eugenio Alabiso, Nino Baragli)

The legendary ending of this film is known for its use of extreme close ups, mid-range shots, and the grand finale where all of those glares and inspections come together. While the footage is half of its climax’s success, the other half is due to the fierce editing work that pieced these images together. Let’s forget the ending as well, because one scene does not make a case for an entire film.

While there are many instances of these quick cuts that set the pacing for a scene (the man with no name shooting off the hats of bystanders, for instance), the entire film is beautifully strung together. “The Good, The Bad and the Ugly” may be a case of the greatest uses of different shot ranges to command a scene.

All of the close ups, wide shots, and varying angles are worked with giftedly. You see what the characters look at and how they appear looking at these fascinations. You cut to your own reactions (say, if a hanging character is slipping off of their perch) and suddenly become a spectator again. You are invited to be right up against these criminals, but are also graciously sent back a little bit to get out alive.

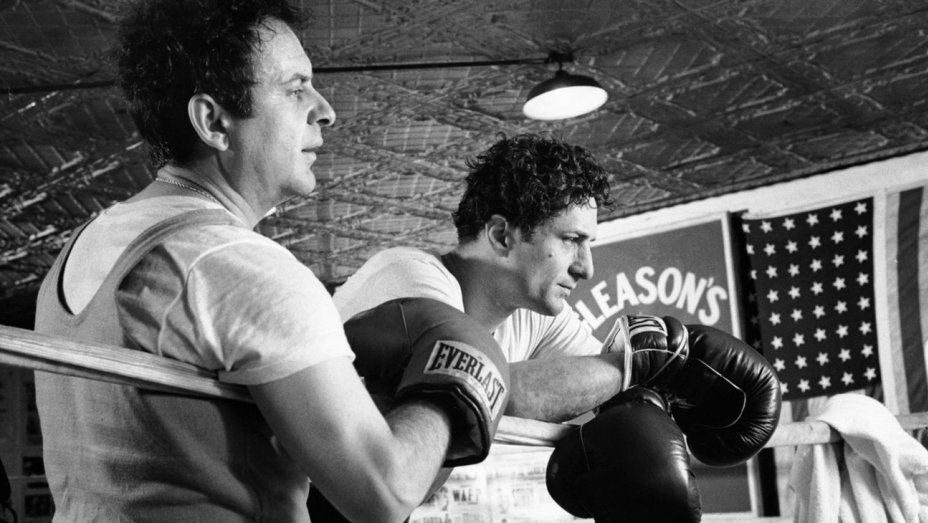

1. Raging Bull (edited by Thelma Schoonmaker)

If there is one editor you need to know about, it is Martin Scorsese’s main woman Thelma Schoonmaker. She has been the seamstress that has stitched together his films for decades, and she is the first person to thank for many of the adrenaline rushes you get from Scorsese’s films. While she has many great films to her name, it almost goes without saying what her magnum opus is when it comes to “Raging Bull”.

There is almost too much to mention when it comes to the sheer brilliance Schoonmaker brought to the way this film is cut. It firstly fulfills its job as a cohesive visual story, where the shots switch at just the right time, the pauses are left where they are required, and each cut feels like an appropriate head turn to what the scene is focusing on.

When Schoonmaker gets flashy, it is reminiscent of Jake LaMotta’s steps in the ring. Schoonmaker’s spatial relationship between shots is some of the best in film history, where movement from one shot to the next flows effortlessly.

Finally, when she decides to get creative, the film knocks you with fierce uppercuts. The slow-downs, use of quick still shots, and speed-ups are tastefully tossed in to create a cinematic miasma within the arena (and it always works). If you want to see editing that covers the basics well and pulls off some experimentation perfectly, then become familiar with Thelma Schoonmaker’s job on “Raging Bull”, the best editing work in film history.

Author Bio: Andreas Babiolakis has a Bachelor’s degree in Cinema Studies, and is currently undergoing his Master’s in Film Preservation. He is stationed in Toronto, where he devotes every year to saving money to celebrate his favourite holiday: TIFF. Catch him @andreasbabs.