5. Zodiac

America is a country obsessed with serial killers and the Zodiac killer is one of the most mysterious and notorious of these to have intrigued and horrified the American public at any time. Based on the non-fiction book by Robert Graysmith, a cartoonist whose life become consumed by the case, David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) follows the manhunt for the killer during the late 1960s and 1970s, in what would turn into one of the country’s most infamous unsolved crimes.

The film and director seem like a perfect match: Fincher being a well-known perfectionist attached to a story of procedure and obsession. Interestingly, Fincher essentially became intrinsically part of the story, when he and his production team spent months before shooting conducting their own investigation into the murders, interviewing witnesses and experts in a new examination of the Zodiac evidence, mirroring Graysmith’s obsession. Luckily for the viewer, Fincher and his writer James Vanderbilt manage to portray the narrative with clarity and conciseness, not becoming subsumed by the wealth of material.

The film feels authentic in its consistency in following the methodological nature of the police and investigators pursuit of the Zodiac; the screen is never overwhelmed by chases, shootouts, any needless action. It feels like a companion piece to Fincher’s earlier serial killer film, the influential Seven (1995), but with contrasting presentations: gone is the stylized gloom and theatrical killings, in favor of a clinical and ponderous study of a murderer and his treachery.

Everything feels just right with the film, from Fincher’s pacing, letting the investigation play out as it truly did, to the visuals and design, with the digital cinematography providing each frame and view of San Francisco and the Bay Area with an intense richness.

Zodiac is an elegant entry in the cinema of psychopathology, capturing America at a key period, as the freedom of the 1960s was replaced by the uneasiness of a new, more closed-off decade: a film about an unresolved murder case seems sadly apt to accompany this.

4. The Tree Of Life

Some film experiences are overwhelming in their immersiveness; some overwhelming in their elusiveness. Some are both, and The Tree Of Life (2011) is an example. Terrence Malick’s epic is a spiritual and philosophical journey perhaps only matched by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) in scale.

It represents the director’s reckoning with the very nature of our human existence and the mysteries of the universe. We see an astonishing sequence showing of the universe being born: flames flickering in darkness, visions of distant galaxies, volcanoes erupting, asteroids crashing. The narrative then focuses on the O’Briens, as the film connects the workings of the greater universe with one Texan family in 1950s America.

Malick wants to portray the battling tensions of Nature and Grace, with Brad Pitt’s stern father representing the former and Jessica Chastain’s mother representing Grace, or nurture. One of their three children dies and we witness another, Jack, as an adult trying to come to terms with this and his whole childhood. What we see, then, are his memories, the hazy, fragmented remembering of his past. These are conveyed in outstanding visuals, and The Tree Of Life is certainly one of the finest films to view of this century, perhaps ever; each frame stuns with its simple beauty.

Malick has to be commended for his incredible ambition, for it takes a confident and intelligent filmmaker to attempt to capture the entirety of life in one piece. By connecting a distinctly American way of life with the whole history of the universe, the film portrays something both specific and universal: the Big Bang created us all and our many stories, and the O’Brien family is just one of these.

3. No Country For Old Men

2007 can be rightly called the greatest year for American cinema in the 21st century so far: it was the year that saw another entry on this list, There Will Be Blood, go up against No Country For Old Men, the two seemingly intertwined by release date, location, and themes.

The Coen Brothers’ film is, however, a more compact piece, a much more faithful presentation of its inspiration, Cormac McCarthy’s mighty novel. It’s ostensibly a crime film, but one that meditates profoundly on things like fate and chance, life and death; it’s both a neo-noir and a neo-western, a simmering and unsettling take on the genres.

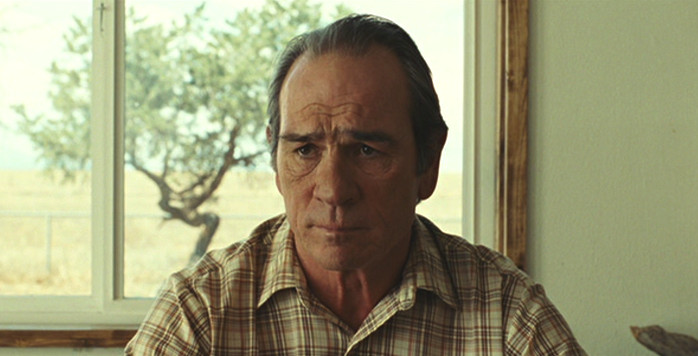

The film takes place in Texas, fertile ground for the Coens, and the harshness of the arid landscape appears perfect for the tale of hunter and hunted, destiny and self-determination. The modern crimes of the story are contrasted against the typical narratives of the ‘Wild West’, symbolised in the character of Sheriff Ed Tom Bell: he comes from the older cowboy tradition and is struggling to maintain order in a changing world, not necessarily for the better.

Retiring soon, the Sheriff retreats from new evil which he cannot fathom and doesn’t want to. This evil is shown through Javier Bardem’s iconic villain Anton Chigurh, a calculated but casual killer. He’s menacing in a disquieting manner, a clear intelligence lurking behind his random violence.

Sometimes he deigns the fate of a victim to the toss of a coin, highlighting the ideas of chance and destiny. Indeed, all the main characters, including Josh Brolin’s Moss, trying to make away with drug money he finds in a field, are burdened by the weight of destiny against will: each are torn, whether it be Sheriff Bell resigning himself to the idea of evil pervading in a new world, or Chigurh maintaining that death is everywhere and nothing is sacred.

To this end, the Coens aren’t interested in the conclusions the crime narrative, in who leaves with the money; rather, they put the focus on the primal urges at work in the psychology of the characters. No Country For Old Men is meticulous, a flawless masterwork with scenes so suspenseful that one cannot help but be drawn in.

While it provides the usual idiosyncracies of their style (absurd dialogue, for instance), what makes this film rise above their other stellar output is the feeling that it’s all tied to something greater: McCarthy’s already excellent source material provides the dark but powerful themes that they need to unleash a ferocious and contemplative classic.

2. Mulholland Drive

Mulholland Drive (2001) is routinely voted as one of the greatest films of the 21st century, even of all time but upon first consideration it can be hard to decipher. All rationality and realism are replaced by a surrealistic dreamlike vision that may truly only be ever fully known to the director David Lynch himself.

It would be hard to find a film which represents more accurately the inner workings of its creator’s mind; Mulholland Drive is overflowing with ideas, themes, hints and secrets. Initially conceived as a TV pilot, it only became a feature film after being rejected; indeed, this is noticeable in the finished film, which proceeds at a leisurely enough pace to begin with before exploding in its later moments.

The surface plot concerns an aspiring actress, Betty, who meets an amnesiac woman, Rita, hiding in an apartment belonging to Betty’s aunt. The plot then includes seemingly unrelated episodes which eventually come together in the mysterious narrative. Little else can be explained to the outsider: it’s definitively a film which has to be seen to be even remotely followed.

Messy and cryptic though it may be, Lynch’s audacity and imagination can only be acclaimed. Most critics maintain that no one explanation fits the film, and perhaps this is the point, for Mulholland Drive can appear like a view of the subconscious, Lynch’s subconscious, where nothing makes sense and nothing truly should.

When fragments do emerge from the chaos, or a moment of feeling escapes, it’s entirely up to the viewer to subjectively consider what’s meant. To watch the film, then, is to watch a surreal master at work, and to watch a Hollywood film from an unbelievably unique voice.

1. There Will Be Blood

Paul Thomas Anderson’s definitive masterpiece feels like a modern cousin to Citizen Kane: a resolutely American epic, a sprawling, overwhelming study of an American-made man.

Inspired by the Upton Sinclair novel Oil!, it follows Daniel Plainview, played by Daniel Day-Lewis, during the oil boom in Southern California in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He starts as a silver-miner before ruthlessly gaining tremendous wealth as an oilman.

At 158 minutes, the film covers a large number of themes, including American ideals like capitalism, greed, and family. It’s the first of these that is truly captured. Plainview grows into a titan of industry, a quintessentially capitalistic, self-made man, but he achieves it all through underhanded tactics and greed. As the film builds to its bombastic conclusion, Anderson wants us to know that wealth has rotted Plainview’s core.

There Will Be Blood received due acclaim upon release in 2007 and after (the New York Times recently named it as the best film of the 21st century), and much of this is because of its true ensemble feel: it’s a remarkable example of talent performing to their highest level throughout production.

Daniel Day-Lewis rightfully won his second Academy Award for Best Actor for the role, as he exhibits the powerful self-destruction of Plainview, losing all of his humanity in the conquest of success. Opposite him, Paul Dano surprised with his ability to hold his own against such an iconic performer, in the twin roles of Eli and Paul Sunday.

Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood provided an intensely sinister score that seemed to creep down from the desert hills themselves. Robert Elswit’s cinematography, found the beauty in stark scenes like the oil well consumed by flames. All these elements enhanced Anderson’s greatest achievement to date. It’s a period piece with so much more to it; an epic for the ages.

Author Bio: Conor Lochrie is a Glaswegian currently travelling and working in New Zealand after 4 long and arduous years at university which he survived with a degree in Central and Eastern European Studies. Unsurprisingly, he now works in a warehouse but would much rather be watching and writing about cinema.