What makes a cult sci-fi film? Usually, they’re movies that were misunderstood or overlooked upon their initial release. More often than not, they were financial failures. Some are hidden gems, genuinely brilliant pieces of work that were inexplicably ignored or mishandled; others succeed in another fashion, becoming quoted and cherished for reasons that are maybe different than the filmmakers intended (the “so-bad-it‘s-good“ film, if you will).

It’s a big world and there are a lot of films out there, hundreds upon hundreds that are very easy to miss if you’re not willing to dig a little. Listed below are ten science fiction films that deserve more of a cult following:

1. Starcrash (1979)

In 1977, American producer Nat Wachsberger approached a young Italian filmmaker named Luigi Cozzi with the opportunity to write and direct a quick Star Wars cash-in.

The film was shot in Rome on a budget of $4 million and managed to attract a surprisingly eclectic cast, including Christopher Plummer (paid the princely sum of $10,000 per day), Marjoe Gartner (an evangelist preacher turned actor), David Hasselhoff (he contracted food poisoning and had a masked stand-in perform much of his part), and British exploitation queen Caroline Munro (looking impossibly beautiful).

The hackneyed plot of Starcrash is, in all honesty, hardly worth examining – it involves The Emperor of the Galaxy and his son who has been taken prisoner by the evil Count Zarth Arn (the late, great Joe Spinell). Blatant unoriginality aside, this is an unintentionally hilarious classic, chock full of laughable special effects, poorly dubbed dialogue, and terrible performances (the entire cast seems either confused or slightly embarrassed).

Shot over a period of 18 long months, the labor behind its creation is always apparent and here we arrive at the true reason for its bizarre success, the reason why it‘s impossible to hate Starcrash: Cozzi deeply cared about this silly movie and his love of cinema, his gratitude, is constantly apparent.

Nearly every single thing in Starcrash is wrong but it’s charmingly ambitious, bears no signs of laziness. The man’s cinematic passions and obsessions pepper the film, which moves at a frantic pace and explores an impressive number of different worlds and environments.

Stop-motion monsters, armies of bikini-clad space babes, weirdly multicolored stars, caves, beaches, snowy valleys – there’s a lot going on in Starcrash. Dime-store set design, sometimes so flimsy that backdrops appear on the verge of tipping over, occasionally possesses a surreal, poverty-row kind of beauty.

In retrospect it’s easy to appreciate all these flaws, to sit back and revel in the sheer ineptitude of it all, but one can hardly imagine how shocked the film’s financers were when they got a look at what they’d helped create.

Indeed, American International Pictures balked at the finished project and refused to release it; luckily Roger Corman’s company New World picked it up for distribution. Veteran composer John Barry provided an excellent score but was (wisely) prevented from seeing the film for as long as possible, for fear that he would quit. Cozzi went on to helm a number of similarly enjoyable genre entries, the best of which being…

2. Contamination (1980)

Contamination was marketed as a sequel to Alien in some territories and that’s not just the work of greedy distributors; writer/director Luigi Cozzi‘s original title was “Alien Arrives on Earth” and he intended his picture to be a direct continuation of the Ridley Scott blockbuster.

The Italian film industry was highly imitative during the 70‘s and 80‘s; one famous quote used to describe this era was, “In Italy, they don’t ask what your film is like. They ask what film your film is like”. Shot in 1979, Contamination utilized some of the same sets and actors as Lucio Fulci’s horror classic Zombie (the two films shared production offices). The picture opens with a massive abandoned ship drifting into New York Harbor.

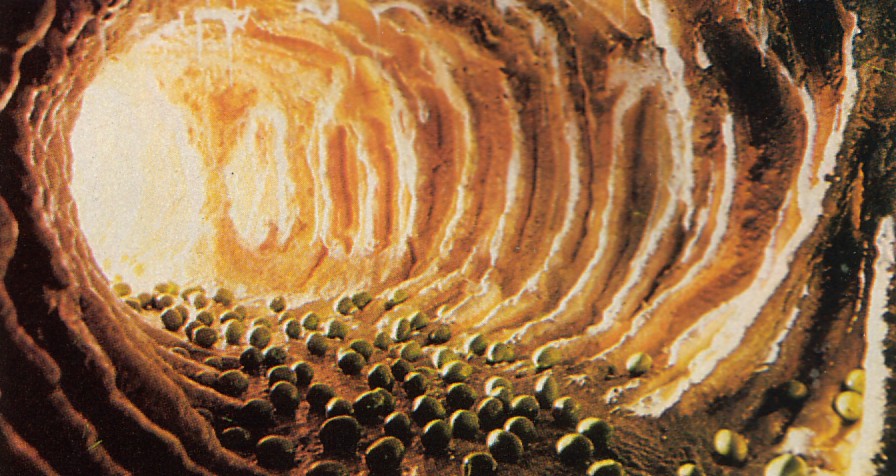

A crew is called in to explore the ghost vessel and on board they discover multiple watermelon-sized, pulsating green eggs that burst upon being touched (or even approached). Inside the eggs is a toxic liquid that causes the human body to explode on contact. These eggs are eventually traced back to their source – a giant alien cyclops that uses human slaves to distribute the lethal pods all across planet Earth.

Not unlike Starcrash, Contamination is technically lacking in virtually every department. The gore effects, relegated mostly to the aforementioned bloody explosions, are largely abysmal and sometimes inexcusably so. Rather than quick-cutting to hide the deficiencies, Cozzi opted to linger on the carnage and even employed the use of slow motion, allowing the audience to clearly observe the bulky explosive devices hidden underneath the actors’ clothing (this is undeniably funny at times).

Acting, writing, cinematography are all a notch up from Starcrash but still woefully lacking, and yet again Cozzi managed to cobble together a movie that effortlessly holds your attention. He ain’t no auteur but he doesn’t care; Cozzi wants to entertain you with monsters, blood, aliens, chase scenes, all that fun silly stuff.

His films are as unpretentious as they come and happily embrace the term ”rip-off” with as much dignity and poise as possible. Italian prog-rockers Goblin provided some of their best music for Contamination (despite the fact that they were down to only two members by this point).

The title theme, Connexion, stands amongst their finest compositions. Horror music has never sounded so damn funky. Watch this and Starcrash back-to-back for an ideal double feature. Pasta strongly recommended.

3. Outland (1981)

It was the early 1980’s and Peter Hyams wanted to make a Western, but at that time it was considered a dead genre. Nobody, it appeared, was willing to finance a film set in the Wild West.

Cleverly adapting to then-popular trends, Hyams conceived of a violent Sci-Fi/Western: essentially a remake of High Noon in outer space. This approach worked and soon the writer/director was off to England with a budget of about $16 million.

Sean Connery portrays William O’Neil, a straight-laced police marshal stationed at a mining colony on Jupiter’s moon Io. When a series of gruesome deaths leads him to uncover a drug-dealing conspiracy within the mines, O’Neil refuses to stand idly by.

Soon he finds himself at war with the nefarious operations manager, Sheppard (Peter Boyle) and fighting for his life against a team of hired killers out to silence him permanently. Sets for the film were constructed at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, where Ridley Scott’s Alien had shot two years earlier, and there are striking visual similarities between the two pictures; they almost appear to exist within the same universe.

All of the environments in Outland are weathered and worn – machinery looks used, floors dirty, air hazy with industrial smoke. Hyams does a wonderful job achieving a dingy, blue-collar atmosphere. He’s always harbored a preference for darkness and shadow; few mainstream studio filmmakers have demonstrated such a fondness for low-light levels.

Outland was the first film to employ the use of IntroVision, a front-projection technique that allowed for an actor, a projected background, and a foreground element to exist together within the frame.

Hyams, a cinematographer who often lenses his own work, hired young D.P. Stephen Goldblatt to use as a scapegoat in case anything went awry with the IntroVision process; despite Goldblatt’s screen credit, it was Hyams who shot the majority of Outland.

This was his show, from top to bottom. The admittedly one-dimensional characters are well cast and sharply written. Connery, as magnetic as ever, provides just the kind of tough guy machismo that the story calls for, and Boyle makes a great opportunist slimeball.

Jerry Goldsmith’s tense, claustrophobic score seamlessly merges synthetic and organic instrumentation. One of the first scores from Goldsmith to feature extensive use of the synthesizer, it helps strengthen both the traditional storyline and the far-out setting. All these elements combine to make one hell of a movie. Outland works so well that you almost wish it were longer, or that other movies like it existed. It at least makes one yearn for more films with bloody deep-space shotgun battles.

4. Galaxy of Terror (1981)

A team of space explorers lands on a distant planet that houses a malevolent entity in Galaxy of Terror, a grisly Alien knock-off from producer Roger Corman. Corman is a man who knows how to make the most out of meager resources.

Consider, for example, the previously discussed Starcrash: that film, which appears to have been made for the combined sum of about five grand, amazingly had a budget of four million dollars. Galaxy of Terror was produced for a modest $70,00 and looks like it cost five times as much.

Spaceship interiors are fairly convincing, especially when one learns that the walls were patched together from Styrofoam McDonald’s containers. All the visual effects – matte paintings and miniatures, models and opticals – are entirely practical, in-camera magic from a bygone era. You’ll spot several familiar faces, including Erin Moran (Joanie from Happy Days), Ray Walston, and a very young Robert Englund.

Definitely a hybrid of horror and science fiction, Galaxy of Terror boasts an antagonist that possesses the ability to read thoughts; victims are subjected to physical manifestations of their worst fears, brought to life by an unfeeling life force (the plot is vaguely reminiscent of Michael Crichton‘s novel Sphere). Crew members are knocked off one-by-one in a variety of inventively gruesome ways, the plot unfolding rather like an intergalactic slasher film.

Unquestionably the most memorable moment occurs when the ship’s resident hottie is sexually violated by a massive, slimy worm creature. This is a legendary moment of raw B-movie sleaze, apparently written as a typical kill scene but changed at the last minute to something far more insidious.

That radical switch is somewhat emblematic of director Bruce Cark’s whole approach – when you’re making a goofy deep-space horror flick for Roger Corman, why not deliver the goods? Galaxy of Terror is a wonderful piece of late night exploitation. Fun fact: James Cameron was a unit director on this film, and his impressive work led to the directing gig on Piranha II: The Spawning.

5. Trancers (1985)

This is technically a cheat, as Trancers is already a minor cult classic that spawned five sequels. The series, which follows the adventures of a time-traveling cop named Jack Deth (Tim Thomerson), was created by Charles Band for his company Empire; eventually that outfit collapsed and Band formed Full Moon Pictures, where the Trancers franchise continued up until 2002.

The first (and best) of the series begins in the year 2237. Chain-smoking, trench coat-clad detective Deth is on the hunt for his arch-nemesis, Martin Whistler. Whistler, a criminal genius with the ability to transform human beings into mindless slaves (or, ’Trancers’), has time-hopped back into 1980’s Los Angeles.

Utilizing a particularly clever method of cinematic time-travel – a drug is injected that allows him to possess the body of an ancestor – Detective Deth travels back to 1985 and becomes his long-dead relative, an LAPD officer named Weisling. What follows is a wild goose chase across the City of Angels, Deth in hot pursuit of Whistler; along the way Deth crosses paths with a cute new-wave girl (Helen Hunt) who helps him acclimate to everyday life in the mid-80’s.

Charles Band is an astoundingly prolific filmmaker who’s managed to rack up 50 directing credits since 1980, but he isn’t exactly a master stylist. He knows how to keep things moving, how to cater to his audience, and with Trancers he had himself a particularly tight little script. Jack Deth is a wonderfully realized character, both on the page and on-screen.

Underappreciated actor Tim Thomerson handles the part perfectly, becoming a futuristic Phillip Marlowe and never taking himself too seriously in the process. Many post-apocalyptic/time-travel action flicks from this period are rather dark, infused with a sense of gloom and menace, but not Trancers: Band’s film is quick, bright, and funny while providing ample thrills, a bit of shoot-em-up violence, and a handful of nifty concepts. Hands down Charles Band’s strongest work as a director.