5. Mulholland Drive – David Lynch

From Twin Peaks to Inland Empire, much of David Lynch’s work has worked within the lexicon of interpretations of classical Hollywood imagery.

In Mulholland Drive, Lynch uses the familiar imagery and style of Golden Age-era Hollywood films, but challenges the authenticity of the emotions or reasoning behind these often referenced cinematic sentiments in order to craft a surreal and paranormal exploration of the nature of fame or perhaps the insolubility that these cultural images of the Golden Age have with the reality of human experience.

He juxtaposes seemingly innocuous images that are familiar to us as viewers of Classic Hollywood film (Large dance numbers, 1950s-inspired musical scenes or the film-within-the-film’s sequence set in a Hot Rod, reminiscent of teen movies of the era, such as Rebel Without a Cause.)

This being said, one of Lynch’s favorite films is Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, another surrealistic film dealing with the nature of fame and the way the implacability of the images’ illusion can influence reality or one’s perception of it. Sunset Boulevard was an oddity upon its release, with its’ Academy Awards contemporaries being Cukor’s Born Yesterday, and Vincente Minnelli’s Father of The Bride, both films which were heavily moulded in the Studio System.

Sunset Boulevard tapped into the sort of disillusion of both movie producers and audiences over the nature of cinema as escapism. Mulholland Drive could perhaps to be made in the spirit of Sunset Boulevard, a critique of the entertainment industry, but yet at the same time, a love letter to it. Perhaps Lynch; like Wilder, knows that nostalgia and disenchantment are two sides of the same coin.

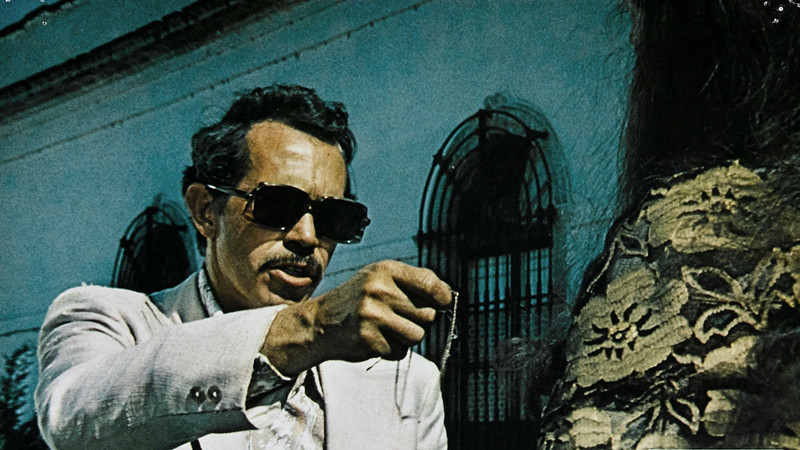

4. Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia – Sam Peckinpah

Peckinpah’s Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia, upon its original release was seen as one of the worst films ever produced by a variety of critics, such as Roger Ebert and Michael Sragow. It has had a resurgence as a cult hit recently, perhaps due in part to its adherence to traditional “western film structure combined with Peckinpah’s depiction of contemporary Mexico which is seen as realistic and inviting of analysis.

Alfredo Garcia is through and through a revenge film indebted to the work of John Ford (specifically The Searchers) and the violence present in gangster films of the pre-code era (from the beginnings of commercial cinema until 1934, when the Motion Picture Production Code enforced by the MPAA after 1934.)

The film though narratively straightforward, uses conventions set by its predecessors in the Western genre as a sort of compass, or perhaps guide map by which Peckinpah operates his direction.

This isn’t to say that its adherence to formula is to its detriment. Rather, by employing a modernisation of these tropes, Peckinpah asserts that traditional narratives (in this case, a revenge story) can be modernised while still retaining their influences.

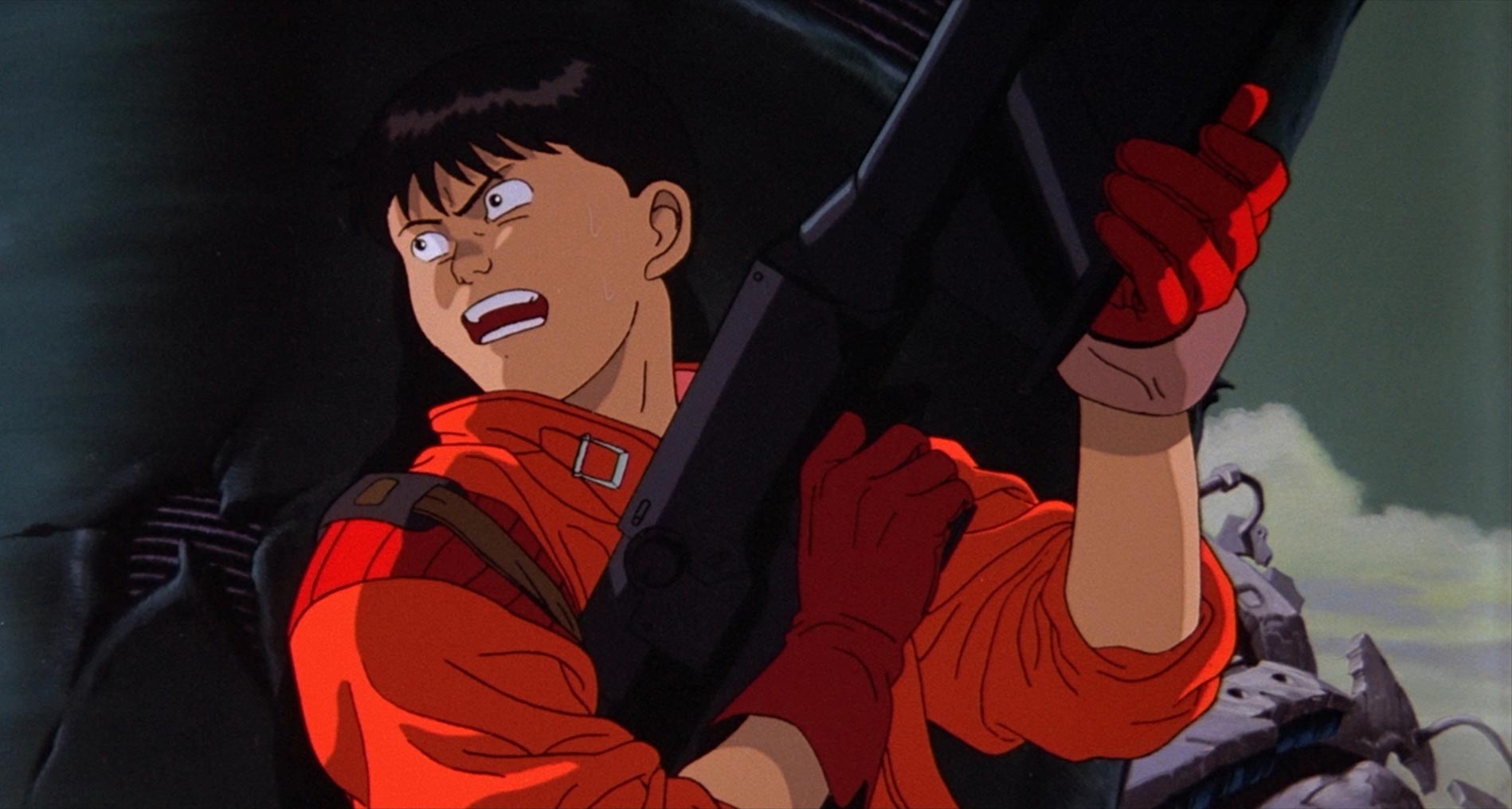

3. Akira – Katsuhiro Otomo

Otomo’s Akira may seem like a strange addition to this list, and though Otomo was influenced by many ‘New Hollywood’ directors and films, he does however have an intense predilection for classical Hollywood cinema, particularly the films of Arthur Penn (who straddled the line between Golden Age-era filmmaking and the ‘New Hollywood’-era.).

Particularly, Otomo was influenced by Penn’s The Chase as well as his more well-known film Bonnie and Clyde (arguably one of the first ‘New Hollywood’ films).

Though Otomo shifted from graphic art into filmmaking, his framing is very reminiscent of Penn’s framing choices in both The Chase and Bonnie and Clyde, with Otomo favouring medium shots of his ensemble cast and close-ups of his protagonists, with his intent to use these shots in order to convey the emotional impact of his sequences.

With The Chase, in particular, Otomo evokes Penn’s use of a protagonist “trio”, perhaps seeking to impart a sense of camaraderie between his characters.

Though Akira also owes a debt to 1980s cyberpunk, he attempts to synthesize classical motifs within the context of a sci-fi moral parable, which in fact continues the precedent that a repackaged narrative can become new through the use of standardized techniques held over from the Golden Age-era of Hollywood.

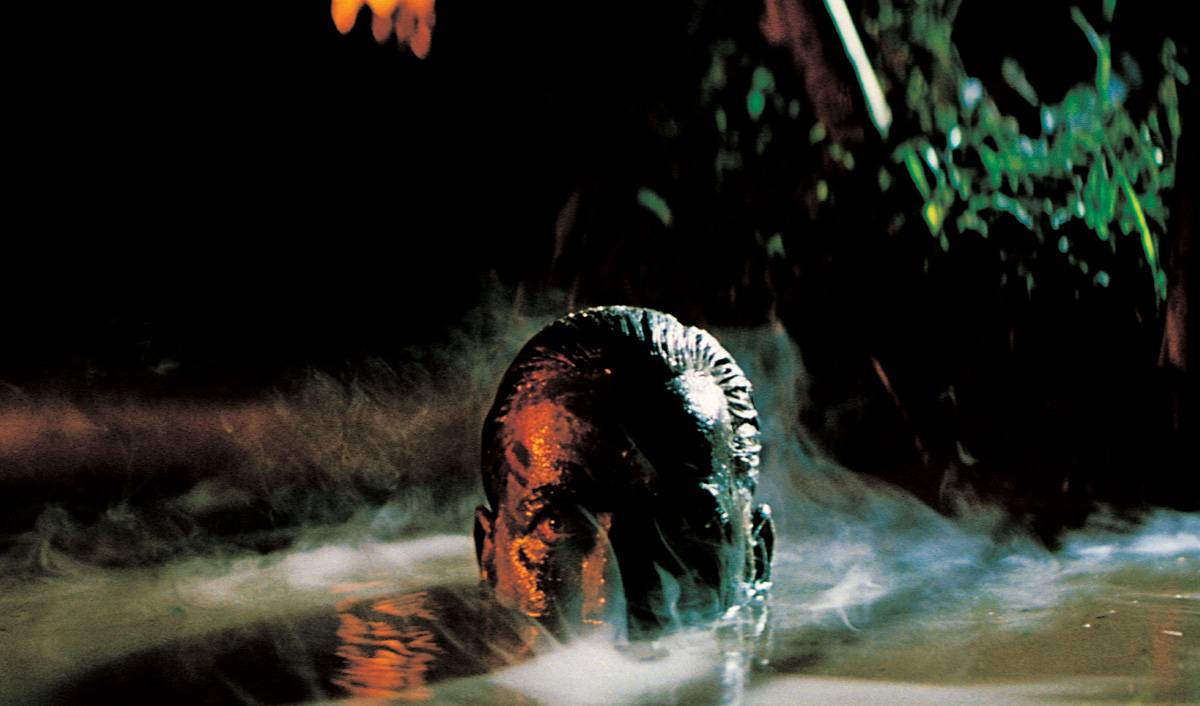

2. Apocalypse Now – Francis Ford Coppola

Coppola’s 1979 anti-war epic is not only influenced by Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, particularly as it relates the moralism and results of war (by way of colonialism and neo-colonialism), but it’s style is beholden to the emotional qualities significant to classical Hollywood film aesthetic. In particular, Coppola channels the works of F.W.Murnau (particular his 1929 romantic drama, Sunrise).

This is not to say that Apocalypse Now is a romance film, but rather that Coppola uses the contrasts set by Murnau in Sunrise (the relations between people, the earth and their place in the world as evidenced by Murnau’s focus on the negative space between actors, with the earth becoming a sort of secondary character itself, perhaps allowing the filmic space for the audience’s reflection).

This sort of “space for reflection” as created by Murnau and utilized by Coppola offer both of their audiences a philosophical “headspace” allowing for a more fluid contemplation of events unfolding within their respective films. Negative space can be used as a form of invitation, or perhaps an evocation of the audience.

Both films deal with the nature of human interaction, and the conflict between individuals (in Sunrise, Murnau speaks to the conflict between two lovers, where in Apocalypse, Coppola uses the same methods to speak to military and cultural conflict.) In the end, both films achieve a sense of intersection between individuals and the external forces that motivate them.

It serves to point out that there is a certain universality in the human story of conflict and that perhaps the same thing that motivates us toward love and reconciliation can also move us toward aggression.

1. The Last Temptation of Christ – Martin Scorsese

Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ; starring Willem Dafoe, from 1988 is an exercise in reference to the Classical Hollywood era of filmmaking. Scorsese lingers in closeup on Dafoe’s face throughout the film, drawing in part on Hitchcock’s work in the 1950s and 60s, allowing the audience a window into the mind and soul of the film’s characters.

Through this, we are able, as an audience, to emote with Dafoe as Jesus, contemplating his thoughts and feelings not as a messianic figure, but simply as another human being.

In Christ; Scorsese, like Hitchcock, understands the emotive capacity of lingering closeups as well as the efficacy of tracking shots, such as the sequence in which we follow Dafoe across a beach, with cuts between Dafoe and his surroundings. This shot brings to mind Hitchcock’s use of cross-tracking, particularly in Psycho. The effect of this technique is the leading of the audience’s perception toward a goal or ultimatum.

In the case of Psycho, the goal was the Bates house, where Vera Miles learns the truth about Norman. In The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese is less concrete in terms of the location he wishes to bring his audience, but in this sense it could be said that the goal to which the audience and Dafoe reach is not strictly physical, stretching out toward the horizon.

Again, Christ is important as a love-letter to the Hollywood Golden Age, like many other films on this list, it uses common and familiar techniques, and even narratives toward a more modernist end.

A reformed story, repackaged and renewed for an audience already well versed in the conventions of cinema to which all filmmakers are indebted.

Author Bio: Alan is a writer, musician and composer from Calgary, Canada. His short fiction has been previously published in L’Allure des Mots out of Miami FL. His music can be found on Spotify and iTunes.