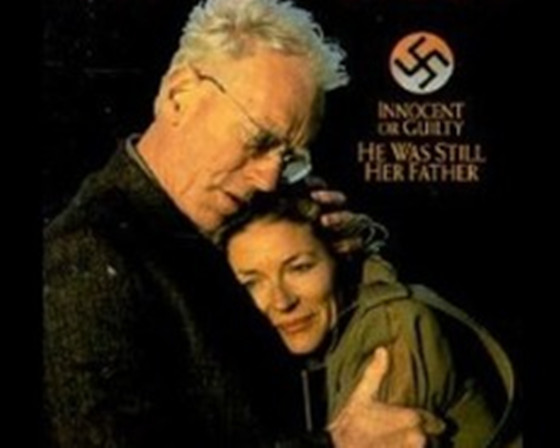

7. Father (1990)

In this drama, a daughter defends her aging father against scandalous accusations. Joseph Mueller (von Sydow) was born in Germany, but emigrated to Australia shortly after the end of World War II. Joseph is happily spending the autumn of his years doting on his two grandchildren and giving friendly business advice to his daughter Anne Winton (Carol Drinkwater) and son-in-law Bobby (Steven Jacobs), who have inherited the hotel that Mueller founded. One morning, as Joseph walks his grandchildren to school, he discovers that a camera crew is following him from a distance, led by reporter Leah Zetnick (Julia Blake).

A few days later, Leah broadcasts a report alleging that Joseph is in fact Franz Kessler, a former member of Hitler’s SS and a war criminal responsible for the death of Leah’s parents, among many others. Suddenly besieged by the media, Anne and Joseph go into hiding after authorities issue an indictment against him. Joseph eventually steps forward to stand trial, defended by attorney George Coleman (Tom Robertson).

After George calls Leah’s credibility into serious question in court, Joseph is cleared of all charges, and a seriously distraught Leah commits suicide in front of Joseph and Anne. But Joseph’s casual reaction to Leah’s shocking act makes Anne wonder if Bobby’s suspicions about her father’s past might have a basis in fact. Von Sydow and Blake both won Australian Film Institute awards for their performances.

The film has the exact plot shared by “Music Box”, Costa-Gavras’ 1989 film. Like “Music Box”, war crime accusations are the trigger for a father-daughter melodrama. Unfortunately, Drinkwater’s Anne is a far weaker presence than Jessica Lange’s headstrong lawyer in the American film. Her character is supposed to have inherited Mueller’s strength and obstinacy, but instead, she always seems intimidated by him. So “Father” is left with a hole at the center, not helped by a plot in need of tightening.

On the other hand, von Sydow’s Mueller is superior to that of Armin Mueller-Stahl’s in “Music Box”. Of course, von Sydow’s presence can justify almost any film, but there is only one way to play this role: just as Mr. Mueller-Stahl did in “Music Box”, with an ambiguous look of distress that could signal guilt or an unjust accusation.

The film reaches toward some powerful questions: Is everyone capable of barbarism during a war? How can someone prove he is innocent if a television report labels him guilty? But it settles for a neat, forced ending. “Father” is not a lurid film; it is just inadequate to the deep and painful story it tries to tell.

8. Citizen X (1995)

Fighting to catch a serial killer against all odds is a pathologist, played to excellence by Stephen Rea in one of his strongest performances. He must battle the snail-pace of Russian bureaucracy, the primitive resources he has at his disposal, and (above all) the refusal by his superiors to acknowledge that the USSR even has a serial killer. The general in charge (Joss Ackland) says that serial killers are “a decadent, Western phenomenon.” Only Donald Sutherland is willing to help, but his help must be under the counter.

Von Sydow plays a Russian psychiatrist who breaks protocol and decides to help the investigators in their quest. It is the first time in Russian history that a psychiatrist is used to build a profile of a serial killer still on the loose, and he has everything to lose if his involvement is made public.

Though appearing only near the end of the film, it is the scene at the end where von Sydow’s psychiatrist reads that profile to him that is most compelling. Von Sydow brilliantly conveys the psychiatrist’s sense of anguish as he realizes that the “patient” is the monster in the profile.

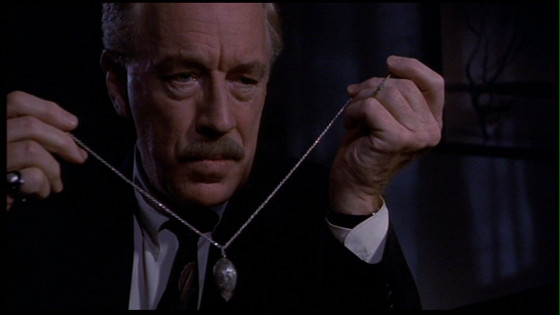

9. Needful Things (1993)

“Needful Things”, the film from Stephen King’s bestseller about a demonic gift shop owner reducing a New England town to bloody chaos, is a movie about the horror of answered prayers; the dangers of getting what you want. Placed in the small town of Castle Rock, Maine (the same town as in “Cujo”, “Dead Zone” and “The Dark Half”), followers of King’s work were not surprised to see another King film rooted in Maine.

It’s not like the usual horror thriller; it has ideas as well as jolts, themes as well as special effects, characters as well as gore. But, as adapted by writer W. D. Richter and director Fraser Heston (the son of Charlton Heston), these “Things” seem disappointingly diminished, squeezed, and stuffed into a box too small.

Von Sydow provides the film’s greatest compensation: his hair-raisingly suave, murderously genial performance as satanic Leland Gaunt, proprietor of the odd green-awned emporium Needful Things. He arrived much like the man from “Something Wicked This Way Comes”: very under the radar and with an agenda brewing.

Von Sydow plays Gaunt perfectly as a man whose Old World manners belie his stated origins – Akron, Ohio – and whose propensity for finding his customers’ deepest desires and then converting their gratitude into enslavement and malice (pulling “pranks” on their neighbors) gradually brings the town of Castle Rock to a boiling point.

Von Sydow clearly carries the movie. So powerful is his presence that the film seems deflated when he’s offscreen, despite good work from the other actors. Chief among them are Ed Harris as long-suffering Sheriff Alan Pangborn, Bonnie Bedelia as his arthritic inamorata Polly Chalmers, Amanda Plummer as poor lonely Nettie Cobb, and J. T. Walsh as the insufferable local politico Danforth (Buster) Keeton.

10. Hawaii (1966)

“Hawaii” had not even begun filming when director Fred Zinnemann was replaced by George Roy Hill; similarly, the role intended for Charlton Heston ended up being played by Richard Harris (though Heston would eventually star in the 1970 sequel, “The Hawaiians”). Filmed at sea off of Norway, as well as in New England, Hollywood, Hawaii, and Tahiti, it took seven years to translate “Hawaii” from script to screen – and almost that long to make back its $15 million cost.

The film is an adaptation of James Michener’s best-selling novel of the same name. Perhaps “snippet” would be a better word than “adaptation,” since this film focuses on only a brief section of Michener’s gargantuan book, the time frame of which was spread out over several centuries, with the film concentrating only on the years 1820 to 1841. Still, Michener’s basic point, that the virginal sanctity of the Hawaiian islands was forever shattered by the incursion of the white man, remains intact.

The film features a towering performance by von Sydow as Abner Hale, a rigid, fire-and-brimstone reverend who arrives on the islands with his new – and infinitely more compassionate – wife Jerusha (Julie Andrews) by his side. His close-mindedness ultimately proves to be more wicked than the carnal attraction Jerusha still feels for a former flame (Richard Harris), or the vast majority of the locals’ hedonistic tendencies.

Rising stars Gene Hackman and Carroll O’Connor head the supporting roster, although it is Jocelyne LaGarde who nabbed the most praise for her delightful turn as Malama Kanakoa. “Hawaii” was a sizable box office hit, yet while it did land seven Oscar nominations, only one was in a major category: Best Supporting Actress for LaGarde, the only non-professional in the cast.

11. Emotional Arithmetic (2007)

A moody but satisfying drama, “Emotional Arithmetic” is a story of bad memories haunting survivors of a World War II French transit camp for Jews, where young American girl Melanie and young Irish boy met and shared the trauma of prison, with the older Jacob (von Sydow) forging a powerful bond.

Adapted by Jefferson Lewis from the novel by the late Matt Cohen and directed by Paolo Barzman, “Emotional Arithmetic” unfolds primarily against the scenic countryside of Quebec’s Eastern Townships region, where the American-born Melanie (Susan Sarandon) lives on a small farm with her history professor husband David (Christopher Plummer) and their grown son Benjamin (Roy Dupuis). Despite the serenity of this bucolic setting, however, something seems off-kilter right from the start.

Perhaps it is the way everybody keeps asking Melanie if she has remembered to “take her pill.” Or it could be Barzman’s penchant for filming the characters staring meaningfully at the horizon, across rolling hillsides and quiet lakes. David, we learn, is recovering from a recent heart attack and has turned somewhat bitter in the face of old age.

Melanie, meanwhile, is a survivor of the Drancy “transit camp” on the outskirts of Paris, where Jews were detained by the Vichy government before being shipped off to Auschwitz – memories that intrude on the present in the form of staccatoed black-and-white flashbacks.

Torn apart and scattered to different lives, they are reunited in 1985 when Melanie discovers that Jacob has just been released from a Soviet work camp. She makes contact and invites him to the Quebec farm where she now lives with David, her husband of many years. Jacob brings with him a surprise guest: Christopher (Gabriel Byrne), who we discover had wanted to marry Melanie, but was too late.

Other revelations come forth during the afternoon and evening, creating an emotional equation that includes several multipliers. One of these is that both Jacob and Melanie have suffered some mental disturbances, the former through terrible treatment at the hands of his captors, and the latter through internalized and obsessive memories of the camp.

The brittle nature of Melanie’s marriage is partly explained by David’s outburst about her harboring six million Jews in the attic, whose fates so consume her that the problems of her own family seem irrelevant. A snappy remark, to be sure, but it conveys much, and earns a knowing reply from Jacob, who notes that it is collateral damage caused to the families of the prisoners from the camps.

It is Jacob, too, who admonishes himself for telling the young Melanie all those years ago to remember – and to record the camp’s activities in a logbook for future reference – instead of telling her “to live”. The impeccable cast help make this somber work engaging, and its setting in Quebec is sufficiently different to give the subject matter a sense of freshness.