“One of the most polarizing movies in recent years.”

– Richard Roeper

Stranger in a strange land

Geometric circular shapes coalesce and converge in an abstract play of light and gloom, almost like a constellation or the orbital trajectory of planets, until, looming large, a sinister eye seems to burst into being, staring directly at us, the audience, or, to be more precise; humanity at large. Thus begins British director Jonathan Glazer’s (Sexy Beast) surreal and highly stylized new film, Under the Skin.

Working from Michel Faber’s 2000 pitch dark sci-fi satire novel of the same name, Glazer’s Under the Skin is an altogether different beast. With the formal grace of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the quasi-documentary and carefully composed sensibilities of Claire Denis––Trouble Every Day comes to mind––and the slow cinema spirit of Kelly Reichardt or Lynne Ramsay (the Scottish hills and silent ingenue suggests the latter’s Morvern Callar, for instance).

Glazer’s ambitious art film, nine years in the making, may harken to the aforementioned auteurs and some of their signature works, but make no mistake, this is a jaw-dropping original work of artifice, and also as close an approximation to Nicolas Roeg (Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell to Earth especially) as we will most likely ever see.

“Hypnotic, unsettling, and haunting, Jonathan Glazer’s arty science-fiction opus is one that hasn’t left my thoughts… It’s a testament to how incredible Scarlett Johansson is in the role that one of the world’s most beautiful actresses can disappear into her part. A startling performance in a uniquely sinister film.”

– Edgar Wright

The heart is a lonely hunter

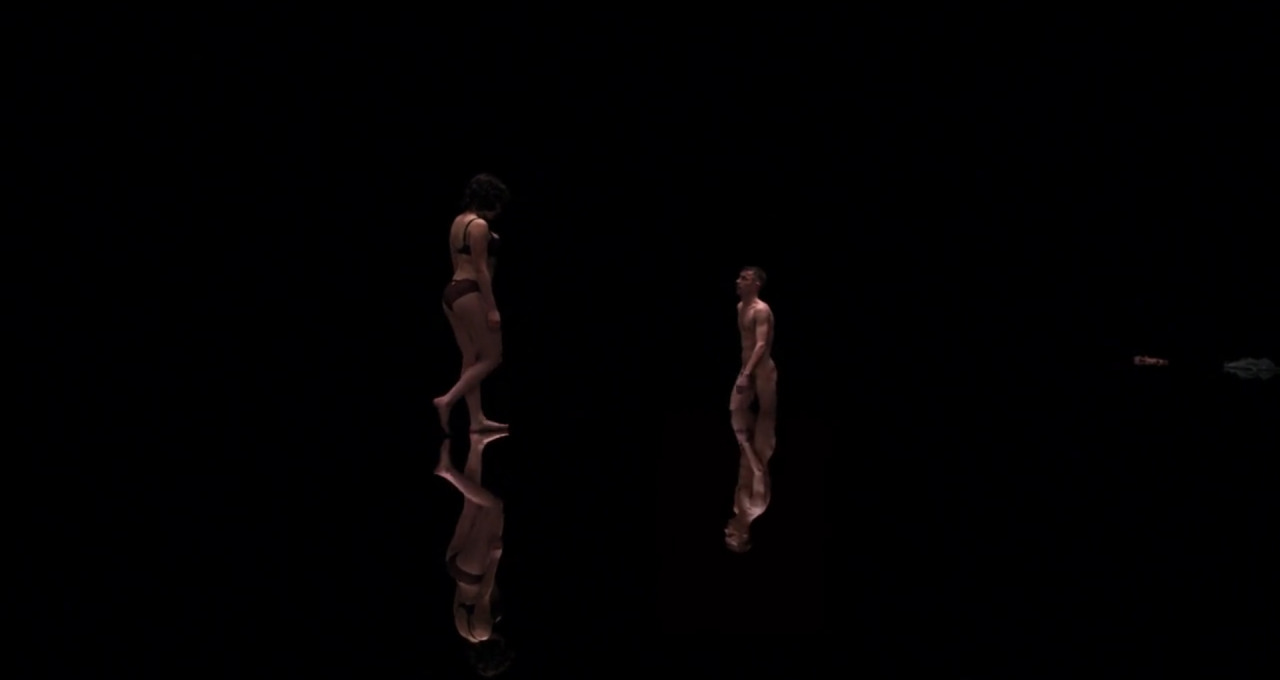

“Is this a dream?” asks a disconsolate and deformed young man to Scarlett Johansson during a particularly profound, almost sacrosanct, instance in the film. The man, played by Adam Pearson (who, incidentally, in real life suffers from neurofibromatosis, which has given him incongruous facial disfigurement), has stripped naked for her, as she has for him.

As seductress and femme fatale, Johansson (in the film she has no name though in Faber’s novel she goes by Isserley), finds herself moved by this gentle man, who’s lonely and alienated in a similar way to her. Our anti-hero, a female extraterrestrial who to this point has decoyed and destroyed umpteen working-class men, hitchhikers mostly, strays from her established schema, for better or worse.

Johansson’s come-hither hottie is more complex than you’d expect and doesn’t at all resemble the waif warrior shibboleth she’s portrayed in other films –– or that other, lesser starlets such as Kate Beckinsale and Milla Jovovich now seem synonymous with.

Her unnamed virago is about as far removed from her Black Widow character in the Marvel superhero films as can be––although that character’s nom de plume is more apt here––in what, to this point, is the performance of her storied career. In fact, if this role doesn’t place Johansson into the upper echelon of actors than nothing will.

Controlled, confident, and cold, Johansson is the ultimate voyeur and severed outsider. The men she seduces aren’t necessarily nasty, most are quotidian saps, easy marks played largely by unknowns.

Glazer hid some eight cameras in Johansson’s van and had her approach real passersby on the street (afterwards they were approached by production assistants to secure permission and payment). This bold foray into surveillance cinema adds to the provocation and authenticity of a hypnagogic yet totally unaffected nightmare.

“Much of the film was shot with a camera called a OneCam, which we built to make this film. We needed a camera that was small enough to hide, but had the quality that we needed to project and do the visual-effects work. It didn’t exist, so we built it. We built 10 cameras. Sometimes we used two, sometimes we used 10. We shot much of the film like that, where we could build the cameras into the dashboard in [Scarlett Johansson’s] car, or hide them in street furniture to watch her walking down the street, and not alert the general public that there was any filming going on at all. Much of the film was shot covertly like that.”

– Jonathan Glazer

Alas! It’s all abyss

Nothing in Glazer’s previous films, Sexy Beast (2000) and Birth (2004), both becoming but comparatively mainstream, apart from some surreal sidestepping and taboo content, anticipates or augurs the fata morgana full-throttle horror unleashed here. Is it challenging? Absolutely. Is it ambitious? Almost to a fault.

Mica Levi’s unnerving, senses-rattling, and panic-inducing score adds to the excitation and existential dismay exquisitely. Levi’s modern compositions convey a strangeness and a sinister desolation that’s not unlike Gyorgy Ligeti’s “Atmospheres” which anticipated and accompanied the appearance of the monolith in 2001. And like that film, Under the Skin has been met with polarized reactions. But isn’t it better that way?

“Watching [Under the Skin] feels like a genesis moment—of sci-fi fable, of filmmaking, of performance—with all the ambiguity and excitement that implies. It’s as if director and star have gone into some alien space to discover what embodies a person, exposing the interior dynamic of psyche and soul and its relationship to the exterior.”

– Betsy Sharkey, Los Angeles Times

A multi-formed nightmare without release

As Johansson stalks, seduces, and destroys the male denizens of Scotland, haunting the highways, thoroughfares, night clubs, filling stations, shopping districts and the countryside, too, she moves from childlike cherub to rouge-lipped iconoclast. Her lair, which I won’t delve much into here, occupies an otherworldly, mercurial, Escher-like lacuna, an abstract artifice with its own curious cosmology. Having visited it in viewing this film I fear future nightmares will indeed take me there again.

The chilling third act, which I’ll also remain tight-lipped about, suffice it to say takes Johansson’s seductress on a landslide initiated by Pearson’s earlier tangible isolation. An isolation she understands all too well, and which takes the narrative into even more unsafe altitudes which reach a crescendo of full-stop shock that lands like a lightning bolt. Days later after my initial viewing I was still processing what it is I’d seen.

At its finish I somehow dragged myself, gob-smacked, out of the theater, having gazed into the abyss. In that inky void the viewer can make out faces that will meet their gaze and return it unblinking. Under the Skin is an elaborate and ethereal experience, one that makes most other films perfunctory and plum. It is a great work from Glazer, a rare talent who can tamper with the familiar in astonishing and unforgettable ways.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.