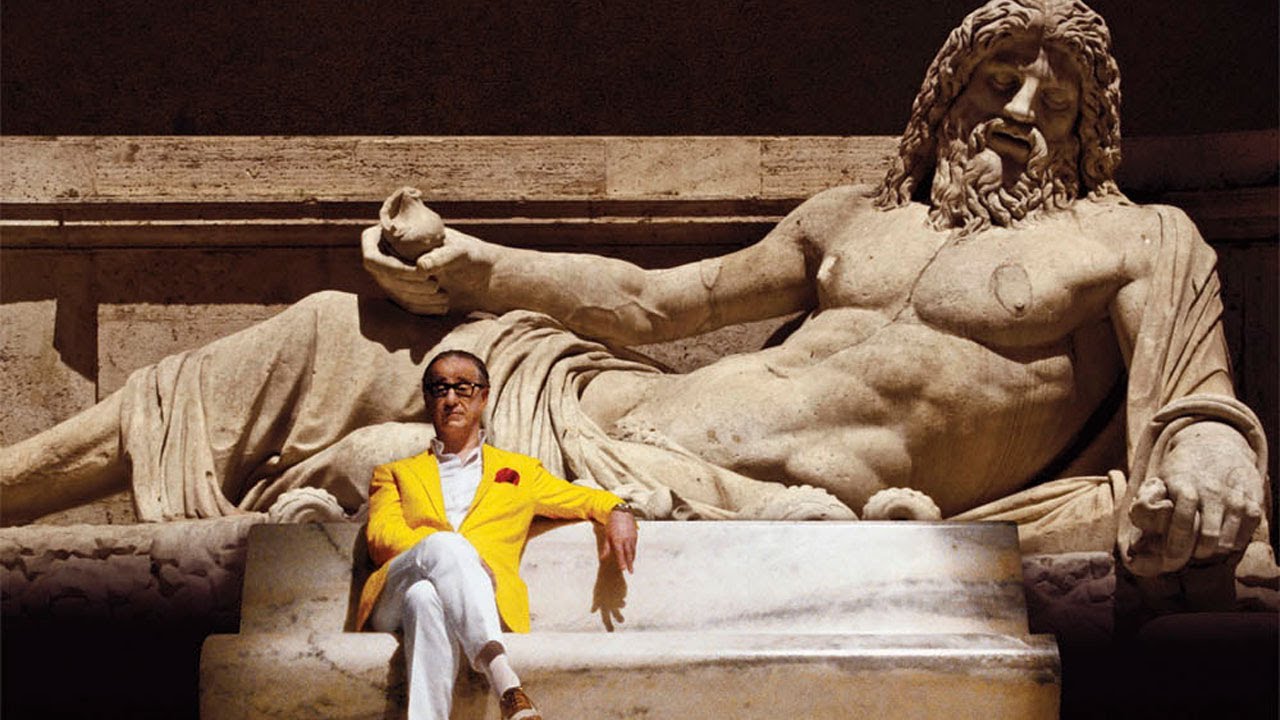

Extravagant. Tragic. Beautiful. These are the words that can describe Paolo Sorrentino’s “The Great Beauty”, a movie that won him an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film of 2014.

Sorrentino’s work is compared to Federico Fellini’s; this movie is thematically similar to “8½”, and with its vivid colours and circus-like imagery, it surely reminds viewers of the work of the great Italian director. Still, Sorrentino’s style is definitely something new and it exceeds the limitations of cinematic language.

The film’s vigour and dynamics can be attributed to its tragedies and cynical humour. The dialogues are intelligent and witty, and when the point of excess is reached, Sorrentino delivers more of it. The movie’s lack of self-imposed limits in storytelling and visual language is what gives it a rarely seen and unique character.

The film opens with a quote from Louis-Ferdinand Celine’s “Journey to the End of the Night”: “Travel is useful, it exercises the imagination. All the rest is delusion and fatigue. Our journey is entirely imaginary. That is its strength.” The journey that Sorrentino presents is powerful because it is imaginary as well; its main strengths are in its creative departure from the ordinary, and the synthesis of the various types of art.

The film tells a story of an artist, Jep, in his mature years. Surrounded by beauty, he seeks for it, he longs for love, and when he gets it, the loss is instant. It is interesting that he stays in one place all the time; he is caught up in Rome’s lavish nightlife, and due to his unwillingness to exercise his own imagination, he has written only one novel.

After his journey, which is presented in the film, he has travelled a long way. Soul searching and loss, dialogues with his companions, the memory of beauty brought to life again, all of this managed to stir a creative force in Jep. In this article, seven reasons will be presented why “The Great Beauty” is a “tour de force”; Jep’s journey will be analysed as well.

1. Portrait of the artist as an old man

In his “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”, James Joyce writes about the shift from a stage of hedonism to the one of religious practice. Jep Gambardella does not seem to be concerned with religious matters very much; he lives the life of enjoying women and parties that last the whole night. Søren Kierkegaard, a Danish philosopher, thought that there are three different stages in which a human can live.

The first is about aesthetics and implies hedonism and celebrating the sensual. If we follow Kierkegaard, Jep lives in this stage. The second is ethical, and an example of that is loyalty to one’s spouse. Jep says that he let people down in his life. Also, he says that at a funeral it is immoral and disrespectful to cry. Yet he cries at the funeral.

The third stage is religious, for Kierkegaard as a Christian, and the most sublime one. Jep denies the value of ethical and religious stages of life, and like Don Juan, he embraces the aesthetics. According to Shoshana Felman, Don Juan’s sexual escapades are potentially infinite, and each one of his “targets” is replaceable. Jep says he does not really know how many women he had slept with; he is not good with numbers.

2. “Synthesis of the arts”

The term “Gesamtkunstwerk” is used to describe Richard Wagner’s operas and it also means “a total work of art” as well as it means a synthesis of all art forms in one work. A more accurate term for Wagner’s works is “musical drama”, to emphasize the idea of the synthesis of drama and music, and other various art forms.

Sorrentino manages to create it with “The Great Beauty”; the music, the picture, and the acting are all-encompassing, and they complement each other. In the first scene of the movie, a cannonball is shot, and a choir and a soloist sing while the camera shows “Fontana dell’Acqua Paola”.

The camera shifts to a Japanese tourist taking a photograph of Rome, who dies at that very moment. Afterwards, the camera shows white Rome bathing in the sun while the focus is on the soloist. In this scene only, music and drama are interconnected. A small musical drama takes place in front of our eyes.

Conceptual art is shown a few times during the movie. In contrast to Rome’s statues and architecture, it shows the transformation of art in contemporary times. It also adds new layers to the film’s narration and its artistic imagery. The mosaic made of photographs of a man, taken every day during his life, has a dramatic and a visual component, adding up to a new art form in the film’s rich imagery and composition.

Music in the film has a wide scope, from David Lang to Bob Sinclair playing at the parties. It intensifies the movie’s key moments, but also follows the narration and diversifies it. The film has great dramatic power; sometimes it looks innocent in its humour, and at other times the themes it explores are grave, but its aesthetics make it wonderful, even in the saddest moments.

3. Spirituality is omnipresent, yet absent

At the end of the movie, a nun is shown climbing the stairs on her knees. Her asceticism represents a contrast to Jep’s lavishness. She gives Jep a remarkably simple answer to his lamentations about searching for beauty. She says that roots are useful, and that’s why she eats them.

Jep’s grandiose search is pointless in the eyes of a person who lives a simple life devoted to God. The morals may be that in the simplest things in life there is beauty, because we need them. “The great beauty” for which Jep was searching for is an illusion.

In Federico Fellini’s “8½”, Marcello Mastroianni’s character says to the cardinal that he is not happy. The cardinal tells him that he is not supposed to be happy; he should live his life being devoted to God and search for salvation. A pope-to-be seems to be concerned more about the recipes for meals than spirituality; this reminds viewers of Luis Buñuel’s critique of the church oligarchies.

Jep Gambardella lives surrounded by religious institutions. He emphasises that you can learn a lot by living near them, but that does not seem to have any influence on his lifestyle. Jep wants to ask a cardinal a question, the content of which we can only guess. Spirituality does not seem to mean much for Jep substantially, but its mysterious power makes him curious about it, at the very least.