Movies are very powerful art form. Some movies people love with a passion, others people hate with a passion. And sometimes their passionate hatred is so strong that it endures long after the film is released.

It’s time to give these films their due. These films provide a very unique experience, but for some reason, they’ve been widely panned by both audiences and critics, and to this day, their bad reputations still hold up like the greatness of a timeless classic.

It’s time to change that. These are five films to be loved and respected:

1. Lady In The Water (2006)

Lady in the Water divided audiences greatly when it came out, and those that did not hate it thought it was merely okay.

But Lady in the Water has an unspoken power that’s grown over the decade since its release. This power was hinted at in Michael Bamberger’s book, “The Man Who Heard Voices” about the production of Lady in the Water. Shyamalan broke ties with Disney over the film during its pre-production faze because Disney’s chairman at the time, Dick Cook, reportedly didn’t understand it. So the project was brought to Warner Bros where M. Night was given the creative breathing room to make the movie he wanted to make.

The result was a collective “meh.”

The general consensus was that Lady in the Water was a self indulgent parade of cliched characters with an overly expositional mythology driving it.

But that’s just what it looks like on the surface. There’s much more going on in Lady in the Water than what the characters go through and what they’re talking about.

The tale of apartment complex handyman, Cleveland Heep (Paul Giamatti) and his discovery of a “Narf” named Story (Bryce Dallas Howard) from “The Blue World” floating in the complex’s swimming pool and all the tenants who join together to complete her mission and bring her back home is just a smoke screen for the story that’s really being told.

This is a story about the grief of the past and hope for the future. About a repressed man coping with loss and how everyone has a function to make this world better.

This was what Shyamalan was really saying while he was spoon-feeding the audience exposition. The mythology and plot twists were on the nose in a very deceptive way because the audience didn’t bother to look beneath it.

What’s funny is, Shyamalan seems to have anticipated the negative reaction, and that reaction is symbolized by the character of Farber (Bob Balaban) a film critic, and the closest thing the film has to a villain. The critics took the character as a slight against them. They accused Shymalan of lashing out against their reception of The Village (another great film) and he was just venting against its detractors by killing off the character before the final act.

But Farber may be the most important character in a film full of important characters.

Because Farber didn’t symbolize critics, he symbolized the public. The majority of public opinion believes there’s no originality left in the world. The majority of the public believes what’s going to happen if something else happens.

And what happens in Lady in the Water isn’t what Farber predicts. He bases his conclusions on story devices. Devices Cleveland follows only to hit dead ends.

Because this is a story about storytelling, and a great story feels like life, and life exists underneath the simple story Lady in the Water tells. It’s a film that shows you nothing but tells you everything to prove you know nothing. It’s Genius!

This is set up in the very first scene when Cleveland Heep kills a very large rat underneath a tenant’s kitchen sink. You don’t see the rat, but you know what it looks like based on how it’s described, and it’s all done in one shot.

To the average viewer, this might look like lazy filmmaking, but it’s actually an example of great storytelling. This is a scene that has everything but the kitchen sink, because you don’t get to see the kitchen sink, because Lady in the Water isn’t about the kitchen sink, it’s about what’s underneath it.

Lady in the Water is a brilliant deconstruction of story tropes that utilizes a large cast of diverse characters whose perceived stereotypes are turned into world changing attributes.

Paul Giamatti’s performance as Cleveland Heep is one of his best. It exemplifies why this well known character actor gets leading man roles. When he unleashes his grief over the murder of his family and yells, “I miss you guys,” with that pained strain in his voice, it’s haunting in a very real way.

M. Night Shyamalan tested the loyalty of his fans with Lady In The Water. It was a passion project people misinterpreted as a vanity piece due to Night’s presence in a major supporting role as a writer who will one day change the world with a book called ‘The Cookbook’.

This was M. Night’s test, and the audience failed. He was telling us, “I’ve learned many things, and I want to share them with you.”

His decision to share what he learned was based on the reaction to Lady in the Water.

And unfortunately, the audience didn’t understand. Much like Disney’s chairman.

So now we have movies like The Last Airbender and After Earth. Remember those? You probably don’t want to.

And why? Because we didn’t listen to M. Night when he gave us the opportunity to hear him. Remember that next time you ask, “Is Shymalan even trying anymore!?”

2. The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990)

Quentin Tarantino once said during a Charlie Rose interview, “Bonfire of the Vanities is a mess, but it’s the kind of mess only a great filmmaker makes.”

That filmmaker was Brian DePalma, who brought Tom Wolfe’s exceptional epic novel about greed and politics to the big screen to the derision of the masses.

The story centers on Sherman McCoy, a married New York Stock broker who drives with his mistress through the bad part of town one night, only to involve themselves in the hit and run of a black inner-city teen that McCoy ends up on trial for– only because the DA thinks he’ll win the minority vote if he puts a rich white guy on trial.

Here’s the thing though, comparisons to the novel aside, if this film came out today, with the same actors in the same roles, it would be considered a socially relevant masterpiece. A film that indicts the divide between races and social classes. It reflects the current controversies surrounding our justice system, and how influences like the Black Lives Matter Movement both better and worsen the issues, and how anyone can get away with anything if they play things the right way.

But people felt that it was too heavy-handed back in 1990. They didn’t appreciate how Tom Hanks could play a despicable and greedy stock broker like Sherman McCoy with the same kind of “nice guy” zeal that defined his earlier comedic roles, but the studio felt Sherman would be more sympathetic if he was likable, an approach critics scoffed at.

And DePalma played ball with the studio to make a masterpiece in disguise. The studio gave DePalma Bruce Willis when he had no actors to play the film’s narrator, Peter Fallow, a drunken journalist whose reporting demonizes McCoy, then inevitably redeems him. It’s one of Willis’s better performances, and he shows range he had never fully shown on screen before that point. This was DePalma’s way of saying, “You can bring me ANY actor, I’ll make him this character!”

The character wasn’t the one Tom Wolfe created in his book, but it worked for the movie. In fact, none of the characters in the movie were the one’s Wolfe created in his book, but they worked for the movie.

Case in point: The judge at Sherman’s trial, written in the book as a white Jewish man, but is played by Morgan Freeman here. There is no better actor that could have played this role, and there is no other actor you would WANT to play this role.

I mean, who else would you want to hear this kind of speech from:

“Let me tell you what justice is. Justice is the law, and the law is man’s feeble attempt to set down the principles of decency. Decency! And decency is not a deal. It isn’t an angle, or a contract, or a hustle! Decency… is what your grandmother taught you. It’s in your bones! Now you go home. Go home and be decent people. Be decent.”

Here’s a link to the scene.

This is a great movie moment from a great movie. But The Bonfire of the Vanities is more than a misunderstood classic, it’s one of the most important films for generations that came after it because it has nothing of value to say about generations that came before it– except maybe that they were wrong about everything.

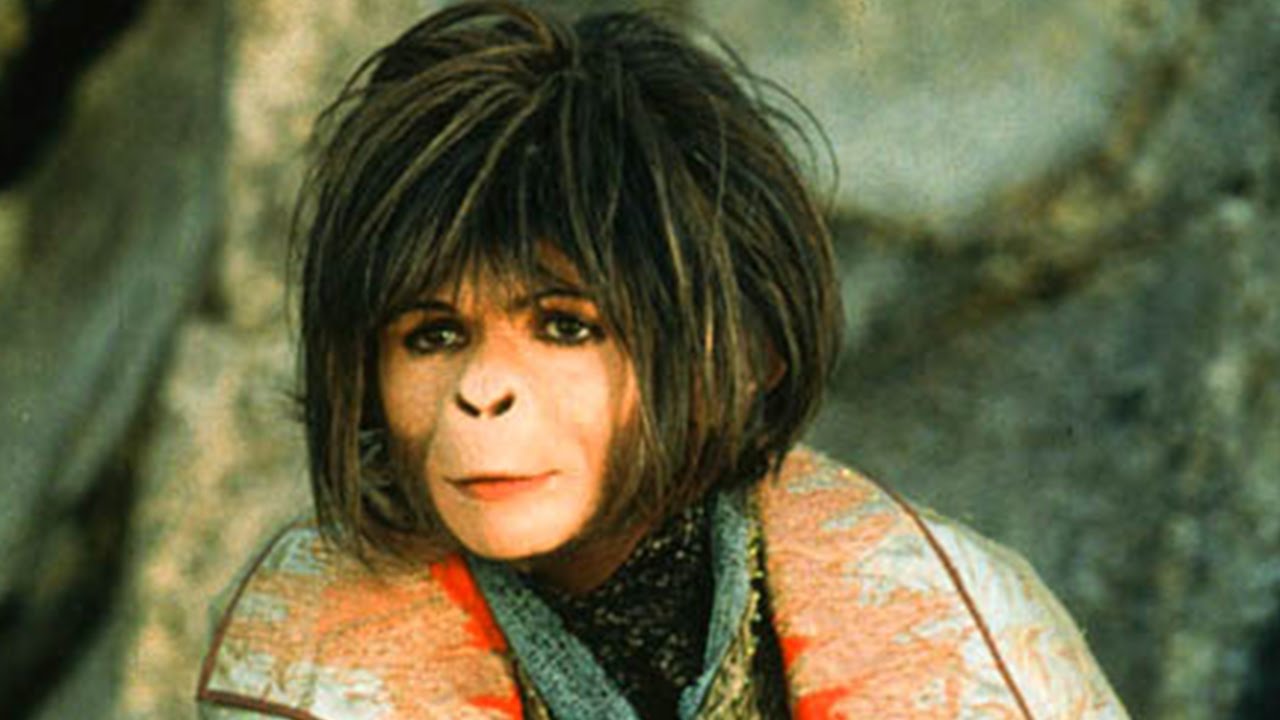

3. Planet of the Apes (2001)

One can argue that Tim Burton’s take on this franchise is canonical with the films that came after it, but most would say that it isn’t– even people involved in making the newer films. And why?…

Because 2001’s Planet of the Apes was terrible! And that ending sucked, right?

That question has a very complex answer.

Planet of the Apes is a close ended film that happens to end with a cliffhanger. A cliffhanger that promises a clear explanation in the sequel, but until then remains a big question mark. And since that sequel was never made, a question mark it remains, and the film is unanimously ridiculed because of it…

But is that fair? Planet of the Apes was a well executed film. Tim Burton got out of his broody comfort zone with that one in order to deliver a true summer blockbuster. And a blockbuster it was. With an opening weekend of over 68 million dollars, the highest opening of 2001’s summer season, it made more than enough money to warrant a sequel. So why wasn’t the sequel made if it was such a hit?

Because it was a sleeper flop.

A film people hyped up and championed long before and after its release, only to realize that it failed to live up to its expectations and they didn’t notice until someone else pointed out its flaws in a convincing way.

Every film has a set of their own shortcomings and it’s up to viewers to decide if they’ll allow those shortcomings to ruin the experience. The Planet of the Apes sequel wasn’t made due to the influence of negative opinion. So they threw everything set up by this film away and started from scratch a decade later.

Marky Mark’s Planet of the Apes could be considered bad because of its ending, but if they followed it up with a sequel taking place in an ape controlled modern America, popular opinion may have turned around on this film. Think about it, “Planet of the American Apes.” That sounds like the best sequel never made! What would have happened in that!?

It appears we’ll never know, but films like Rise of the Planet of the Apes, and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes are starting to fulfill the promise once made by this film.

That’s why it’s up to the fans whether or not to consider this film canonical.