9. Mirrormask (Dave McKean, 2005) / UK | USA

Based on a story co-written by the British multidisciplinary artists Dave McKean and Neil Gaiman, “MirrorMask” is a true gem amongst the myriad of fantasies dealing with a girl’s coming of age and the relationship between a mother and a child.

Seamlessly merging many aesthetic, literary and cinematic influences, from steampunk, through Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” and Henson’s “Labyrinth” and all the way to Adam Jones’s stop-motion music videos for Tool, this hybrid film brims both with symbols and visual inventiveness of the imaginary world.

The surreal, sepia-tinted eye-candies are manufactured on a tight budget with the majority of the animators lifted straight from art school. And they taste even sweeter with the jazzy score by the composer and saxophone player Ian Bellamy.

One particularly memorable scene depicts the heroine Helena’s goth-like transformation which is accompanied by a delicate cover of The Carpenters’ “Close to You” performed by a choir of creepy mechanical dolls. (What we actually hear is the voice of the Swedish vocalist Josefine Cronholm who also sings the ethereal “If I Apologise” once the credits roll.)

10. Prince Vladimir (Yuri Kulakov, 2006) / Russia

Yuri Kulakov’s first foray into feature-length films is an unorthodoxly romanticized, gorgeously animated account of Vladimir Sviatoslavich the Great (cca 958-1015) before the Christianization of the Kievan Rus’. According to its original title, it was supposed to be the first part in the series, but unfortunately, the sequel hasn’t been released to this day.

In spite of being aimed for children (and at some points, preachy), “Prince Vladimir” respects its viewers, so it doesn’t shy away from (subtly) showing plunder and bloodshed, as well as portraying its titular and glorified hero as morally dubious.

Yes, it is true that a fair share of Vladimir’s blame is assigned to an evil Perun’s priest (whose name Krivzha suggests that he is just the embodiment of guilt) and yet, Kulakov and his co-writers do not discriminate their polytheistic ancestors. On the contrary – via the character of Boyan, they point out the light side of paganism and, in the addition, the possibility of living in harmonious relationship with nature.

Which brings us to the breathtakingly painted backdrops of medieval Russia through all the seasons and on the other hand, authentically illustrated architecture, costumes and details of everyday life.

11. OrAngeLove (Alan Badoev, 2007) / Ukraine

Katya is a cellist. Roman is a photographer. Both of them are young, handsome and full for life. Their love is almost autistic and, as the title suggests, the color of their tragedy is orange.

Stylish, fragmented, at times surreal and peppered with mystery in the form of a terminally ill, wheelchair-bound landlord who has a penchant for strange games, this chamber romantic drama plays like a deconstruction of some folk fairy tale. By the end, it turns into a postmodern rendition of “Romeo and Juliet” with HIV in lieu of the feuding families.

Its greatest strength are the soft lighting, mesmerizing cinematography, “weightless” atmosphere and Badoev’s bold experimentation with form and genre conventions. Parts of the film are turned into some sort of music videos/autonomous tableaux which reflect the couple’s extreme infatuation and disconnectedness from the rest of the world.

12. Ikigami (Tomoyuki Takimoto, 2008) / Japan

In the near future of Japan, the government declares the “Prosperity Law” that dictates 1 in 1000 drawn-from-the-drum citizens ages 18-24 will die for the state (with the help of a heart-stopping nano-capsule). The idea behind the horrid lottery is that everyone lives to the fullest (and don’t think too much).

The title of this manga-based Orwellian (melo)drama refers to a “death letter” delivered by the black-suited officials, 24 hours before the “victim” is about to pay his/her debt. During their last day, everything is free of charge and after they’re “processed”, their families are compensated.

Split in three acts, the startling story follows one of the “death mailmen” with a thankless task of informing three young human beings their life is coming to an end. And it is told in such a way that you need a tissue (or even a whole pack), unless you’re made of stone.

An individual’s absolute powerlessness in the cruel dystopian society is pictured in austere fashion, with each flicker of hope mercilessly quenched.

13. Malice in Wonderland (Simon Fellows, 2009) / UK

More than obviously inspired by Lewis Carroll’s most beloved novel, “Malice in Wonderland” follows a one-night adventure of a young American woman (named Alice, of course) in the London underground. The falling through a rabbit hole starts right after Alice runs into a hyperactive cabby, Whitey (get it?), then gets amnesiac and swallows a pill from a bottle labeled “For Your Head”.

On a journey of self re-discovery, the heroine encounters many characters (small, but impressive parts of the British ensemble) amongst whom you can easily recognize pulp-versions of Caterpillar, Cheshire Cat, The Mad Hatter, Queen of Hearts and the rest of the twisted party.

Well directed, exquisitely lighted and tightly framed, this slang-fueled crime-fantasy extravaganza is given extra oomph with the soundtrack – a crazy mix of diverse genres which support the colorful antics. Before watching it, bear in mind that sometimes, in cinematic arts, ‘red’ means ‘go’.

14. The Murder Farm (Bettina Oberli, 2009) / Germany | Switzerland

Based on the German writer Andrea Maria Schenkel’s debut novel of the same name, this atypical thriller (with the elements of horror) takes us back to the 50s of the last century. Two years after an entire family is murdered on a Bavarian farm, Tannöd, the perpetrator hasn’t been caught. When a nurse, Kathrin, arrives at the village, the unpleasant memories of the recent past are awakened and she gets entangled into a thick web of lies and secrets.

Employing two parallel narrative threads, Bettina Oberli and her co-writter Petra Lüschow spin the tale of great evil which is concealed in a small pious community eaten from the inside by anxiety, hypocrisy and intolerance. The omnipresent sense of paranoia is intensified by the claustrophobic environment.

Together with the dim lighting, a dense forest which looks like it’s straight out of the Grimms’ fairy tale adds a lot to a creepy atmosphere and becomes a character on its own. And Stéphane Kuthy’s icy cold photography complements the film’s dark subject matter.

15. Surviving Life (Theory and Practice) (Jan Švankmajer, 2010) / Czech Republic | Slovakia | Japan

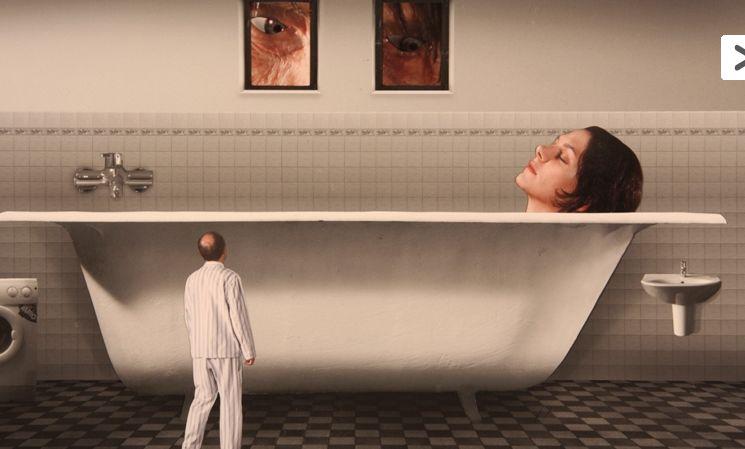

In a witty prologue similar to the one from (an aptly titled) “Lunacy”, Švankmajer demonstrates his weird sense of humor and self-irony by informing the audience that what they’re about to see is “just a poor imperfect substitute for a live-action film”.

Actually, he combines short live-action sequences with a traditional paper-cut-out animation in the vein of children shows and Gilliam’s vignettes for Monty Python’s Flying Circus into a “cheap”, yet visually brilliant “psychoanalytical comedy”.

Focusing on the double – conscious and unconscious – life of a middle-aged, addle-headed clerk, Evžen, the prominent Czech surrealist blurs the thin line between reality and dreams in which an enigmatic beauty in red outfit appears… along with bizarre creatures.

Tongues writhe in ecstacy. Disembodied hands jump out of the windows, while painting nails. An army of horny teddy bears march the streets and a giant snake devours a bald man running in place. “Out-framing” their portraits, Freud and Jung dispute during Evžen’s psychiatric sessions… A must-see.

16. Lollipop Monster (Ziska Riemann, 2011) / Germany

A feature debut for the writer and comic-book artist Ziska Riemann is a brisk, ironic, whimsical and unpretentious modern fairy tale which feels like a more down-to-earth and communicative version of Vera Chytilova’s “Daises”.

Its twisted story about coming of age, seduction and sexual exploration revolves around two seemingly different 15-yo girls, Ariane and Oona, who join forces after a tragic incident and start a rebellion against the adults, without thinking about the consequences of their “mischief”.

Subtly flirting with magic realism, Riemann doesn’t shy away from experimenting with both the narrative and the visuals, so she utilizes monochromatic animated passages, eccentric music-video-like sequences and grainy pseudo-amateur footage in order to depict her heroines’ state of mind at a given moment.

Together with her co-screenwriter Luci van Org, she delivers a film that is simultaneously sour, bitter and sweet. Besides, she has a support of two extremely talented young actresses – Jella Hasse as a frustrated lolita Ariane and Sarah Horvath as a talented goth-girl Oona who are the yin & yang heart of “Lollipop Monster”.

17. The Fifth Season (Jessica Woodworth & Peter Brosens, 2012) / Belgium | Netherlands | France

After their adventures in Mongolia (Khadak) and Peru (Altiplano), Woodworth & Brosens (W&B hereinafter) return home and plunge a picturesque Belgian village from the Ardennes region into an alternate reality of everlasting winter.

A failed attempt at igniting the pyre in a pagan-like rite of spring calls into question a survival of a small community. This newly created situation brings the worst in humans – malice, selfishness and aggressiveness, inter alia – as an increasingly ominous atmosphere is established.

Sumptuously shot by Hans Bruch Jr., “The Fifth Season (La cinquième saison)” is an enigmatic, inexorably bleak and misanthropically inclined drama which explores the themes common to the directorial duo – greed, xenophobia, human-nature relation, a sudden removal from the comfort zone, a conflict between primitive & modern / individual & society, as well as the life hindered by the weight of negative emotions.

W&B’s protagonists or rather, antagonists are best defined in the words of Bagi’s grandfather (from “Khadak”): “How poor we are at defending ourselves.”