These titles may not sound appealing, but considering the time and place they were conceived, it can give the viewer slices of what the golden years of Spanish horror were like; real horror in cinematographic terms. A lack of budget, lack of an established cultural environment, the industry, the audience and critic’s prejudices, and obstacles to adapt the genre to the viewer’s reality and its society were the causes for these films to delay their incursion in the Spanish cinema panorama.

This list explores the most significant titles, that reaches from the fantaterror that appeared during the last years of Franco’s regime, the country’s transition to democracy and the political and social change that led to the dictator’s death.

As Paul Naschy put it on Javier Pulido’s La década de oro del cine de terror español (1967-1976) (The Spanish Horror Cinema Golden Decade (1967-1976)): “When you hit a head with an axe, what you were really doing was breaking a system that caused you a heavy unconscious frustration”.

During the late-Franco period, the ideological burden of horror and fantastic cinema were disguised as gothic allegories, eroticism and gore aesthetics. Some well-known directors of that moment of a more versatile kind took advantage of the industrial conjunction, and tested the waters in horror filmmaking with surprising outcomes providing a personal approach to the genre.

Later, in the 80s, the genre started to move secondly as the industry grew more interested in a certain kind of auteur filmmaking. Nevertheless, low budget horror flicks were produced in Spain during those decades that unquestionably deserve a second chance.

1. Tower of the Seven Hunchbacks (La Torre de los Siete Jorobados, Edgar Neville, 1944)

Edgar Neville was part of a crew of writers and artists that were kept out from the Generación del 27 literary movement that was formed by Rafael Alberti, Antonio García Lorca and Miguel Hernández, among others. Neville and his colleagues cultivated an absurd and humorous tone in almost all of their creations and were in contraposition to what the literary trends were in Spain at the moment.

“Tower of the Seven Hunchbacks” is an adaptation from Emilio Carrere’s homonymous novel about a gambler making a deal with a ghostly apparition, the winning numbers in exchange for protecting the ghost’s niece. The ghost, when alive, was an archeologist who discovered a subterranean citadel where Jews hid from an expulsion order established by Spain and is now inhabited by a gang of hunchbacks.

This film is not a proper horror-fantasy flick, but is sometimes considered to be film noir in many cinema studies, drawing from sources like gothic cinema and German expressionism. Like most of the titles on this list, it surely qualifies as an opener for this retrospective, combining an enigmatic, terrifying and comical atmosphere.

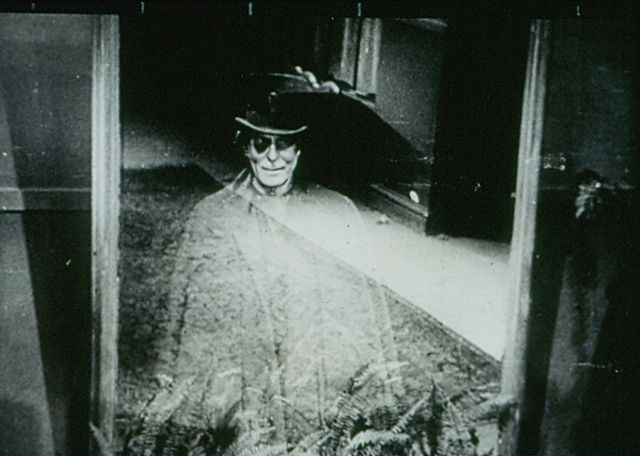

2. The Awful Dr. Orloff (Gritos en la Noche, Jesús Franco, 1962)

Jesús Franco’s Dr. Orloff trilogy is one of the most representative film cycles in Classic Spanish horror cinema alongside Paul Naschy’s Waldemar Daninsky and Amando de Ossorio’s zombie Templars. “The Awful Dr. Orloff” opens the trilogy with a mad doctor character abducting beautiful French cabaret girls and ripping off their skin in order to repair his daughter’s burnt face.

Years before Pedro Almodóvar used Georges Franju’s premise from “Les Yeux San Visaje” in “The Skin I Live In”, Jess Franco applied a similar plot in “The Awful Dr. Orloff” creating a daring and unusual film in an unfavorable context, upon external traditions profoundly customized from cultural hypothesis that synthesized the foreign and Spanish in a unique blend that define Franco’s style.

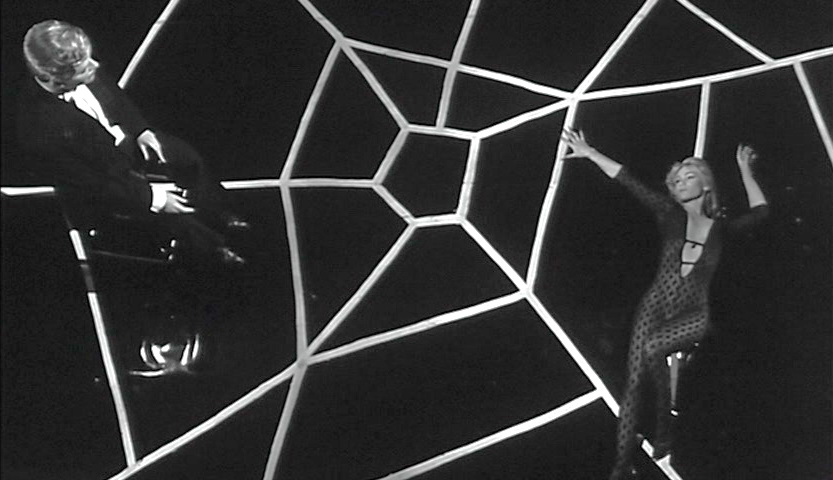

3. The Diabolical Dr. Z (Miss Muerte, Jesús Franco, 1965)

Franco’s quintessential film in aesthetic-formal terms, the plot picks up the Dr. Orloff saga and also some literal elements with an idea spiritually sustained in “Dr. Orloff’s Monster” (El Secreto del Doctor Orloff, 1964). The viewer can catch a glimpse of a continued Franquian universe, as in this film Dr. Orloff appears aforementioned as a precursor of the investigations, the leading role in the film carries out to avenge her father’s death.

With a tone and topic previously unseen, “The Diabolical Dr. Z” rises as one of Franco’s best directing jobs, as well as flawless cinematography by Alejandro Ulloa, bringing it closer to expressionism and comic strips through its filmic form supported by light, shadows and atmospheres. It’s accompanied by Daniel White’s score, a usual collaborator in Franco’s films.

4. Frankenstein’s Bloody Terror (La Marca del Hombre Lobo, Enrique Eguiluz, 1968)

Enrique Eguiluz directed Paul Naschy’s first apparition onscreen as Waldemar Daninsky, a role that enshrined him as Spain’s werewolf. In this essential film, Waldemar Daninsky is doomed with the werewolf curse when a couple of gypsies open the grave of a lycanthrope and the latter bites the count, transforming him into one of his species.

In a time where Hammer Productions and Italian Gothic were the source of fantastic interest in cinema productions devoted exclusively to popular consumption, it’s not surprising that Paul Naschy tried, from the start of the film’s shoot, to bring in some of the topics that nourished international horror in previous years, adopting cinematographic external views in constant attempts to make it more sellable.

Its dynamism puts a mark on a tale that mixes the love story prototype in a classic monster framework, with the usual diatribe of romance being interrupted by a curse of local folklore where the actions that stem from it are based on a quest to break the spell. It’s a wise choice in displaying in a careful and non-excessive way the will to match the classic films of its kind.

5. The Werewolf versus the Vampire Woman (La Noche de Walpurgis, León Klimovsky, 1971)

The Walpurgis Night, as the original title states, is a pagan celebration that takes place in several central and northern Europe countries the last night of April until the beginning of summer. The title and the original concept of the film were changed in order to give a particular impression in other countries. León Klimovsky, an Argentinean director, told one of the last stories of lycanthrope Waldemar Daninsky, with a screenplay from Paul Naschy and Hans Munkel.

Daninsky returns from the dead when two forensic scientists pull out a silver bullet from his corpse, he escapes and sets out on a journey to his castle where he’ll trick two students looking for the tomb of countess Wandesa Darvula, a supposed vampire, and will accidentally revive her.

Again with a low budget, Paul Naschy sorted it out and managed to include in the film every detail he planned in his script, including a sequence of classic horror events like lesbian vampires, not-so-skilled characters that are responsible for evil spreading all over the country, and love setting monsters free from the evil inside them. Spain’s own Lon Chaney Jr. is released from his burden in one of the most unique and representative monster metamorphoses of Spanish film history.

6. Cannibal Man (La Semana del Asesino, Eloy de la Iglesia, 1972)

Eloy de la Iglesia was not a former horror director, best known for quinqui films like “Vallecas’ Tobacconist” (La Estanquera de Vallecas, 1987) or “Friends” (Colegas, 1982) about drugs and delinquency.

With a dissenting, provocateur and naturalistic filmography, de la Iglesia was a subterranean chronicler who also gave us probably the first Spanish slasher film, “Cannibal Man”, about a butcher who unintentionally kills a taxi driver and is forced to kill his girlfriend before she informs against him, and also kills, sequentially, every person who notices or finds out what he did.

It is a physical and sensorial film that reaches the viewer in an uncomfortable and disgusting way, where de la Iglesia introduces an original and sordid proposal of portraying his country’s poor and marginal state. It’s also a reflection in contrast with the outcome of the economic development that made citizens believe in a perfect world over the awful reality of an unimproved society suppressed by a dictatorship.

7. Return of the Evil Dead (El Ataque de los Muertos Sin Ojos, Amando de Ossorio, 1973)

Amando de Ossorio’s blind dead Templar quadrilogy opens with “Tombs of the Blind Dead” (La Noche del Terror Ciego, 1972), and “Return of the Evil Dead” follows with the sound-guided recently awakened characters terrifying a Portuguese town and chasing a group of people hidden in an abandoned cathedral who try desperately to escape. In 1971, when Ossorio restored the tale, the Templars’ damned fame was no more than a gloomy popular myth.

This second installment strengthens its origin and legend through an effective and artisan design rummaging in abyssal iconographies (death as a supernatural hooded entity is a frequent Medieval icon linked to macabre dances, bubonic plague and apocalypse). The secret corners of horror cinema hide subversive potential with limited critical relevance.

The mayor is described as a crooked despot, and the governor is devoted to erotic games with his secretary whilst addressing speeches with the florid regime rhetoric; this scene is shot in a humorous tone with political criticism deactivated in exchange for mocking Francoist provincial power. This apparently trivial turn achieved another type of subversion: the working-class neighborhoods laughing at their leaders.