6. Urban Myth

The pretense of a truth always makes for a more convincing lie. If the writer is going to explore alternate realms and/or sub-culture maybe they should play on genuine rumour and human paranoia. In short, harnessing – even perpetuating – urban myth can be forte for a screenplay, adding credibility, provoking discussion and extending its shelf life.

The strongest example of this in Pulp Fiction are the events going on beneath the pawn shop (Tarantino wanted to use the track ‘My Sharona’ by the Knack to accompany the incident here but members of the band were not in agreement).

Such places exist, often where one would least expect it, for the audience there is a very real possibility this could be underneath somewhere on their street, for them a genuine paranoia or intrigue and there will always be someone who claims to know who and where, thus perpetuating the myth.

Consider here also the Gold Watch story (based on a story originally called ‘Pandemonium Reigns’ by co-writer Robert Avery) imagine how many people have heard and re-told stories like this. As a similar example from another film, the racing driver story from Ealing’s Dead of Night (1945) in which a driver recovering from an accident has a (slightly amusing) premonition concerning his own death, has since passed into urban myth with some claiming it to be founded on a real-life anecdote.

In truth this tale was based on an E.F Benson short story first published in 1906. One wonders given time, how long it will be before like the racing driver, the golf watch passes into genuine urban myth – if that isn’t where they came from already.

For the writer, possibly there is no space for such urban myths in every film but the opportunity to harness and/or perpetuate it could aid a screenplay and extend the shelf life of the finished film by beguiling its audience with ‘half-truths’.

7. Empathy and Character Craft

An audience need to side with a film’s main character(s) in order to follow them through the narrative. If the audience don’t find some sort of common interest, emotional/intellectual engagement or mystery they will sooner or later lose interest in the story. Much was and is made of Pulp Fiction’s slick dialogue (again, something covered in more detail in another list).

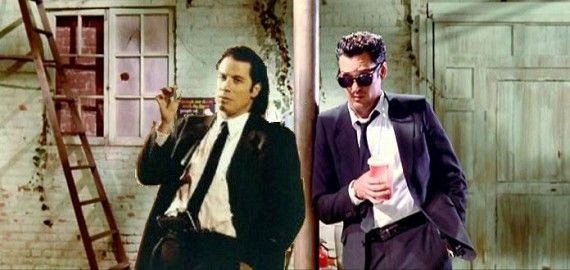

To focus on two of the film’s main anchor points, Vincent and Jules, it can be noted how this dialogue, although at times seemingly rambling about anything unrelated to plot, serves a clear a purpose.

Reconsider the audience’s first meeting with Jules and Vincent, a conversation about burgers and European cultural differences. This conversation is in essence just two guys driving to work discussing holidays and travel, bantering. This banter ‘normalises’ them for the viewer, normalises in terms of what soon follows – a brutal killing.

If it weren’t for the violence, they are just two run of the mill not entirely unlikable characters having amusing conversations. In being amusing the audience should warm to them all the more. It also makes the smooth transition to their violent deeds and back again all the more shocking.

In contrast to other characters Jules and Vincent aren’t as seemingly out of their depth as Brett and his associates, similarly their form of violent justice appears as a higher morality than the rapists below the pawn shop. Again, all this serves to make them more likable to the film’s audience.

Even when dealing with killers and villains, the writer needs to employ some sort of method to get the audience on side with key characters, with Pulp Fiction Tarantino showed us the normal side of the hit man and employed the principal of contrasts.

8. Broaden Your Palette

There was a time when Pulp Fiction was seemingly treated by some as the bluffers handbook on how to write a screenplay. True, as this list evidences, there are many good pointers to be taken from it but the film, like many others, has a far ‘broader gestation’ than the exploitation cinema its creator is known to love.

The screenwriter needs to recognise this and draw from their own broader influences. Tarantino did not invent non-linear narrative, an early example of this can be found in the 1920’s German Expressionist cinema in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, with a narrative effectively following a similar pattern, with the bulk of the story being told in flashback before returning to the beginning for the final sequence.

Other influences on Pulp Fiction were the Noir film Kiss Me Deadly, from which the glowing briefcase motif (allegedly) arises, and Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall (1956) from which Butch’s robes are styled, this film also makes use of flashback.

It is no secret that Tarantino is a fan of French New Wave, the director Jean-Luc Godard in particular. Indeed, Tarantino cites Godard’s 1964 film Bande à part (A Band of Outsiders) as influencing the dance scene in Pulp Fiction, the title inspiring him to name his own early production company A Band Apart (1991-2006).

Again, like many of Godard’s films, 1960’s À bout de soufflé (Breathless) being a key example, Tarantino’s films also feature outsider/criminal characters of no specific profession and contain lengthy dialogue sequences, Pulp Fiction is no exception to these influences.

Pulp Fiction is therefore a text made all the richer for its principal writer’s influences. Likewise, it could also be said that within these ‘crime/criminals’ on screen influences, Pulp Fiction also teaches the writer to research their own scripts by re-visiting previous similar cinematic outings.

There is also the old argument here that bad writers borrow, good writers steal – an audience always likes something they perceive as new but is in fact made up of the familiar.

9. Consider the Potential for Sequels

It might be a highly commercial statement to make but Box Office figures count. If a film is a success, the audience will likely want more and the film maker is in the position to respond. Perhaps, it is wiser to say that the savvy writer should be in a position to anticipate this.

Box Office hits tend move in cycles, producers and audiences are aware of this, if a film is going to make money, it could make even more, and entertain for longer, if there is some potential for sequels. A story should be well-told and resolve but still have those openings for more, revisit the original 1977 Star Wars it works as both stand alone and part of a saga.

Looking back at Pulp Fiction, is it possible to imagine if 1997 had brought us ‘More Pulp Fiction’ instead of Jackie Browne (in some respects perhaps it did) following Jules and hinting at a resolution to just what was in that brief case. Was there was also scope for a spin-off or prequel.

It was the apparent intention to cast Michael Madsen as Vincent Vega (making him the twin of his Reservoir Dogs character) opposite Samuel L Jackson but Madsen had other commitments leaving the way clear for John Travolta to take the role.

One wonders if Tarantino had already considered some movie spin-off potential here, talk of ‘The Vega Brothers’ film as a long term project circulates from time to time, this may have proved a more fruitful venture than Death Proof. It is worth noting that Tarantino was quick to double up with Kill Bill in two ‘volumes’.

With any film, particularly multi-strand movie such as Pulp Fiction, there are various potential avenues for future stories the writer should know when not to venture into as to over-egg the mix in one film but they should not write themselves out of the potential for sequels by either.

10. Changing Times

Pulp Fiction was released in the U.K with an 18 certificate, in the U.S it received an R rating, in short, around the globe it was an adults only film.

Fast forward roughly eight years from 1994 to the pending release of both Spiderman and the first instalment of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, both films which were ‘too much’ for a family friendly PG (parental guidance) both in the US and UK.

In the UK in particular forces behind these two films were at the time incredible wary/fearful that the film would receive a higher classification, which back in 2002 would have been a 12 Certificate, meaning no-one under that age would be permitted into cinemas to see the film.

The fear here was that ‘traditional family audiences’ with younger children would not see the films or perhaps ‘half’ with one parent and older sibling(s) going to see the film – effectively halving potential box office earnings. The 12A certificate was quickly rushed through (roughly the same as the U.S PG-13) meaning that those younger than 12 could see the film if accompanied by an adult.

A glance at the forthcoming films at the time of writing (fourteen years later) reveals the majority of films to now be 12A/PG-13. Tarantino’s own The Hateful Eight (2015) is a notable exception with an 18 classification. This however is the lesson here; the ‘novice writer’ must accept that they are not Tarantino. At this moment ensuring a script has the strongest commercial appeal to agents/production companies seems to mean writing with the 12A/PG-13 market in mind.

The frequent expletives, drug use and general violence of any spec script mirroring Pulp Fiction would likely make any completed film less marketable/profitable, lessening the writer’s chances of success. It should be noted that for the issues above, Columbia TriStar refused to finance Pulp Fiction in the early 90’s, regarding it as ‘..the worst thing ever written. It makes no sense. Someone’s dead and then they’re alive. It’s too long, violent, and unfilmable.’

In the end it became the first film completely financed by Miramax. The writer should be wary of the changing market, in theory the fact that the film was made should have opened up the market, perhaps for a while it did but the lesson here is that times change or rather that they don’t and a film like Pulp Fiction is always going to be a commercial gamble.

As a further point, the writer should also be wary of changing audience views with regard to certain subjects. The internet storm that still rages over the ‘Han Shot First’ issue in the original Star Wars film, altered for moral reasons as he fired in cold blood, is partial evidence of this.

Pulp Fiction, at present escapes this but reconsider the rape scene. Several critics read this as a post-modern reference to a similar notorious incident in Deliverance (1972) but pointing out that in being knowingly referential the true power of the event to shock (as in Deliverance) is lost. In Pulp Fiction, the addition of music also allows the event to be played out with a dark humour – as though ‘for laughs’.

In 1994, perhaps the majority of viewers understood it this way. However, the writer should consider that where once the BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) were in deep discussion regarding the reframing of a needle penetrating an arm for Pulp Fiction’s home video release, as perception of sexualised violence and crimes of this nature change – so to might the way audiences read this scene in the future. Such a scene could damage the lucrative shelf-life of a film.

Regardless, of much of the above, it can still be said that the one thing Pulp Fiction and its success can still teach the writer is that they should write what they are passionate about, trying to second guess markets and what an audience may or may not think in 20+ years is a sure way to stifle creativity. Go on, get writing.

Author Bio: George Cromack is a tutor at the University of Hull and also Coventry University’s Scarborough Campuses; with a BA in Scriptwriting he also teaches evening classes in Creative Writing, Scriptwriting and Film Studies for the WEA. Working towards his PhD focusing on Folk Horror, he is a keen writer of both prose and script, Cold Calling, a film short written by George premiered in October 2013. Follow him on Twitter @MadBasil.